Related Research Articles

Witchcraft, as most commonly understood in both historical and present-day communities, is the use of alleged supernatural powers of magic. A witch is a practitioner of witchcraft. Traditionally, "witchcraft" means the use of magic or supernatural powers to inflict harm or misfortune on others, and this remains the most common and widespread meaning. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, "Witchcraft thus defined exists more in the imagination of contemporaries than in any objective reality. Yet this stereotype has a long history and has constituted for many cultures a viable explanation of evil in the world". The belief in witchcraft has been found in a great number of societies worldwide. Anthropologists have applied the English term "witchcraft" to similar beliefs in occult practices in many different cultures, and societies that have adopted the English language have often internalised the term.

A witch-hunt, or a witch purge, is a search for people who have been labeled witches or a search for evidence of witchcraft. Practicing evil spells or incantations was proscribed and punishable in early human civilizations in the Middle East. In medieval Europe, witch-hunts often arose in connection to charges of heresy from Christianity. An intensive period of witch-hunts occurring in Early Modern Europe and to a smaller extent Colonial America, took place from about 1450 to 1750, spanning the upheavals of the Counter Reformation and the Thirty Years' War, resulting in an estimated 35,000 to 60,000 executions. The last executions of people convicted as witches in Europe took place in the 18th century. In other regions, like Africa and Asia, contemporary witch-hunts have been reported from sub-Saharan Africa and Papua New Guinea, and official legislation against witchcraft is still found in Saudi Arabia and Cameroon today.

Asian witchcraft encompasses various types of witchcraft practices across Asia. In ancient times, magic played a significant role in societies such as ancient Egypt and Babylonia, as evidenced by historical records. In the Middle East, references to magic can be found in the Torah and the Quran, where witchcraft is condemned due to its association with belief in magic, as it is within other Abrahamic religions.

Intersectionality is a sociological analytical framework for understanding how groups' and individuals' social and political identities result in unique combinations of discrimination and privilege. Examples of these factors include gender, caste, sex, race, ethnicity, class, sexuality, religion, disability, height, age, and weight. These intersecting and overlapping social identities may be both empowering and oppressing. However, little good-quality quantitative research has been done to support or undermine the practical uses of intersectionality.

Witchcraft in Latin America, known in Spanish as brujería and in Portuguese as bruxaria, is a complex blend of indigenous, African, and European influences. Indigenous cultures had spiritual practices centered around nature and healing, while the arrival of Africans brought syncretic religions like Santería and Candomblé. European witchcraft beliefs merged with local traditions during colonization, contributing to the region's magical tapestry. Practices vary across countries, with accusations historically intertwined with social dynamics. A male practitioner is called a brujo, a female practitioner is a bruja.

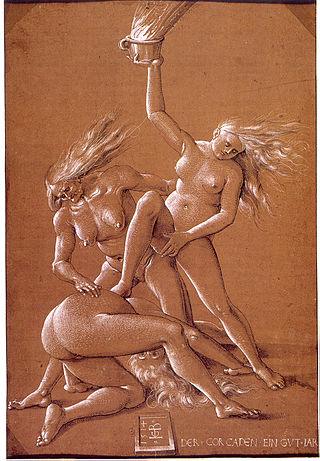

The roots of European witchcraft trace back to classical antiquity when concepts of magic and religion were closely related, and society closely integrated magic and supernatural beliefs. Ancient Rome, then a pagan society, had laws against harmful magic. In the Middle Ages, accusations of heresy and devil worship grew more prevalent. By the early modern period, major witch hunts began to take place, partly fueled by religious tensions, societal anxieties, and economic upheaval. Witches were often viewed as dangerous sorceresses or sorcerers in a pact with the Devil, capable of causing harm through black magic. A feminist interpretation of the witch trials is that misogynist views of women led to the association of women and malevolent witchcraft.

Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw is an American civil rights advocate and a scholar of critical race theory. She is a professor at the UCLA School of Law and Columbia Law School, where she specializes in race and gender issues.

The Basque witch trials of the seventeenth century represent the last attempt at rooting out supposed witchcraft from Navarre by the Spanish Inquisition, after a series of episodes erupted during the sixteenth century following the end of military operations in the conquest of Iberian Navarre, until 1524.

In the early modern period, from about 1400 to 1775, about 100,000 people were prosecuted for witchcraft in Europe and British America. Between 40,000 and 60,000 were executed, almost all in Europe. The witch-hunts were particularly severe in parts of the Holy Roman Empire. Prosecutions for witchcraft reached a high point from 1560 to 1630, during the Counter-Reformation and the European wars of religion. Among the lower classes, accusations of witchcraft were usually made by neighbors, and women made formal accusations as much as men did. Magical healers or 'cunning folk' were sometimes prosecuted for witchcraft, but seem to have made up a minority of the accused. Roughly 80% of those convicted were women, most of them over the age of 40. In some regions, convicted witches were burnt at the stake, the traditional punishment for religious heresy.

Ragnhild Tregagås or Tregagás was a Norwegian woman from Bergen. From 1324 to 1325, Tregagås was accused and convicted of exercising witchcraft and selling her soul to the devil. She was "accused of performing magical rituals of a harmful nature, demonism and heresy" as well as the crimes of adultery and incest with her cousin, Bård. She was sentenced to strict fasting and a seven-year-long pilgrimage to holy places outside of Norway by Bishopp Audfinn Sigurdsson, as documented in his proclamation "De quaddam lapsa in heresim Ragnhild Tregagås" and the sentencing "Alia in eodem crimine". It is likely that Ragnhild Tregagås held a higher social position in Bergen, as the Bishop dealt with her personally and did not sentence her to death. There is little documentation on who Ragnhild Tregagås was as a person. Due to the date of her trial, it is likely that she was born in the late 13th century. There is also no recorded death date for Ragnhild Tregagås. She was married, her husband's name is undocumented, and he died before the trial, likely unaware of his wife's adultery. The trial against Ragnhild Tregagås is the only one concerning witchcraft that is known from medieval Norway, taking place 250 years before the witch-hunt in Norway started.

Throughout the era of the European witch trials in the Early Modern period, from the 15th to the 18th century, there were protests against both the belief in witches and the trials. Even those protestors who believed in witchcraft were typically sceptical about its actual occurrence.

In early modern Scotland, in between the early 16th century and the mid-18th century, judicial proceedings concerned with the crimes of witchcraft took place as part of a series of witch trials in Early Modern Europe. In the late middle age there were a handful of prosecutions for harm done through witchcraft, but the passing of the Witchcraft Act 1563 made witchcraft, or consulting with witches, capital crimes. The first major issue of trials under the new act were the North Berwick witch trials, beginning in 1590, in which King James VI played a major part as "victim" and investigator. He became interested in witchcraft and published a defence of witch-hunting in the Daemonologie in 1597, but he appears to have become increasingly sceptical and eventually took steps to limit prosecutions.

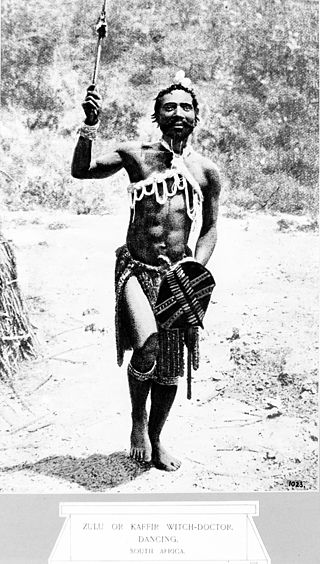

Witch-hunts are a contemporary phenomenon occurring globally, with notable occurrences in Sub-Saharan Africa, India, Nepal, and Papua New Guinea. Modern witch-hunts surpass the body counts of early-modern witch-hunting. Sub-Saharan Africa, particularly the Democratic Republic of Congo, South Africa, Tanzania, Kenya, and Nigeria, experiences a high prevalence of witch-hunting. In Cameroon, accusations have resurfaced in courts, often involving child-witchcraft scares. Gambia witnessed government-sponsored witch hunts, leading to abductions, forced confessions, and deaths.

Witch trials and witch related accusations were at a high during the early modern period in Britain, a time that spanned from the beginning of the 16th century to the end of the 18th century.

Witchcraft is deeply rooted in many African countries and communities in Sub-Saharan Africa. It has been specifically relevant to Ghana's culture, beliefs, and lifestyle. It continues to shape lives daily and with that it has promoted tradition, fear, violence, and spiritual beliefs. The perceptions on witchcraft change from region to region within Ghana, as well as in other countries in Africa. The commonality is that it is not something to take lightly, and the word spreads fast if there are rumors' surrounding civilians practicing it. The actions taken by local citizens and the government towards witchcraft and violence related to it have also varied within regions in Ghana. Traditional African religions have depicted the universe as a multitude of spirits that are able to be used for good or evil through religion.

The Witch trials in Portugal were perhaps the fewest in all of Europe. Similar to the Spanish Inquisition in neighboring Spain, the Portuguese Inquisition preferred to focus on the persecution of heresy and did not consider witchcraft to be a priority. In contrast to the Spanish Inquisition, however, the Portuguese Inquisition was much more efficient in preventing secular courts from conducting witch trials, and therefore almost managed to keep Portugal free from witch trials. Only seven people are known to have been executed for sorcery in Portugal.

The Witch trials in Denmark are poorly documented, with the exception of the region of Jylland in the 1609–1687 period. The most intense period in the Danish witchcraft persecutions was the great witch hunt of 1617–1625, when most executions took place, which was affected by a new witchcraft act introduced in 1617.

The witch trials in Orthodox Russia were different in character than the witch trials in Roman Catholic and Protestant Europe due to the differing cultural and religious background. It is often treated as an exception to modern theories of witch-hunts, due to the perceived difference in scale, the gender distribution of those accused, and the lack of focus on the demonology of a witch who made a pact with Satan and attended a Witches' Sabbath, but only on the practice of magic as such.

In Africa, witchcraft refers to various beliefs and practices. These beliefs often play a significant role in shaping social dynamics and can influence how communities address challenges and seek spiritual assistance. However much of what witchcraft represents in Africa has been susceptible to misunderstandings and confusion, thanks in no small part to a tendency among western scholars since the time of Margaret Murray to approach the subject through a comparative lens vis-a-vis European witchcraft. The definition of witchcraft differs between Africans and Europeans which causes misunderstandings of African conjure practices among Europeans. While some colonialists tried to eradicate witch hunting by introducing legislation to prohibit accusations of witchcraft, some of the countries where this was the case have formally recognized the existence of witchcraft via the law. This has produced an environment that encourages persecution of suspected witches.

The anti-subordination principle(ASP) is a legal doctrine aiming to reveal, critique, and dismantle all forms of subordination. It's based on the idea that equal citizenship is not possible in a society with widespread social stratification. The principle originates from the critical theory tradition. It is often contrasted with the anti-classification principle, which focuses on preventing laws or policies from making distinctions based on classifications such as race or gender, regardless of the outcome.

References

- ↑ Gurvitch, Georges (1942). "Magic and Law". Social Research. 9 (1): 104–122. ISSN 0037-783X.

- 1 2 Ettúf, Qútb (2024). "Magical Law". Academia.

- ↑ Rives, James B. (2003). "Magic in Roman Law: The Reconstruction of a Crime". Classical Antiquity. 22 (2): 313–339. doi:10.1525/ca.2003.22.2.313. ISSN 0278-6656.

- ↑ Ray, Benjamin (2003). "Salem Witch Trials". OAH Magazine of History. 17 (4): 32–36. ISSN 0882-228X.

- ↑ Waters, Thomas (2015). "Maleficent Witchcraft in Britain since 1900". History Workshop Journal (80): 99–122. ISSN 1363-3554.

- ↑ Gray, Natasha (2001). "Witches, Oracles, and Colonial Law: Evolving Anti-Witchcraft Practices in Ghana, 1927-1932". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 34 (2): 339–363. doi:10.2307/3097485. ISSN 0361-7882.

- ↑ "Border Disputes". Salem Witch Museum. Retrieved 2024-09-13.

- ↑ Crenshaw, Kimberle (1991). "Mapping the Margins: Intersectionality, Identity Politics, and Violence against Women of Color". Stanford Law Review. 43 (6): 1241–1299. doi:10.2307/1229039. ISSN 0038-9765.

- ↑ Whitney, Elspeth (1995). "The Witch "She"/The Historian "He": Gender and the Historiography of the European Witch-Hunts". Journal of Women's History. 7 (3): 77–101. ISSN 1527-2036.

- ↑ Dysa, Kateryna (2020). Ukrainian Witchcraft Trials: Volhynia, Podolia, and Ruthenia, 17th–18th Centuries. Central European University Press. doi:10.7829/j.ctv16f6ctn.7?searchtext=witchcraft%20accusations%20jewish%20people&searchuri=/action/dobasicsearch?query=witchcraft+accusations+jewish+people&so=rel&ab_segments=0/basic_search_gsv2/control&refreqid=fastly-default:b42f8a40561078a64913d2bcedc61af1. ISBN 978-615-5053-11-5.