Related Research Articles

Camille Lucie Nickerson was an American pianist, composer, arranger, collector, and Howard University professor from 1926 to 1962. She was influenced by Creole folksongs of Louisiana, which she arranged and sang.

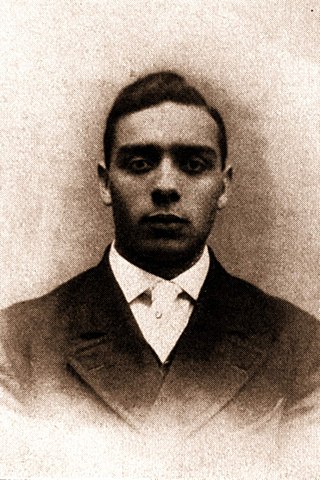

Edwin Bancroft Henderson, was an American educator and National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) pioneer. The "Father of Black Basketball", introduced basketball to African Americans in Washington, D.C., in 1904, and was Washington's first male African American physical education teacher. From 1926 until his retirement in 1954, Henderson served as director of health and physical education for Washington, D.C.'s black schools. An athlete and team player rather than a star, Henderson both taught physical education to African Americans and organized athletic activities in Washington, D.C., and Fairfax County, Virginia, where his grandmother lived and where he returned with his wife in 1910 to raise their family. A prolific letter writer both to newspapers in the Washington, D.C., metropolitan area and Alabama, Henderson also helped organize the Fairfax County branch of the NAACP and twice served as President of the Virginia NAACP in the 1950s.

Sue Bailey Thurman was an American author, lecturer, historian and civil rights activist. She was the first non-white student to earn a bachelor's degree in music from Oberlin College, Ohio. She briefly taught at the Hampton Institute in Virginia, before becoming involved in international work with the YWCA in 1930. During a six-month trip through Asia in the mid-1930s, Thurman became the first African-American woman to have an audience with Mahatma Gandhi. The meeting with Gandhi inspired Thurman and her husband, theologian Howard Thurman, to promote non-violent resistance as a means of creating social change, bringing it to the attention of a young preacher, Martin Luther King Jr. While she did not actively protest during the Civil Rights Movement, she served as spiritual counselors to many on the front lines, and helped establish the first interracial, non-denominational church in the United States.

Alain LeRoy Locke was an American writer, philosopher, educator, and patron of the arts. Distinguished in 1907 as the first African-American Rhodes Scholar, Locke became known as the philosophical architect—the acknowledged "Dean"—of the Harlem Renaissance. He is frequently included in listings of influential African Americans. On March 19, 1968, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. proclaimed: "We're going to let our children know that the only philosophers that lived were not Plato and Aristotle, but W. E. B. Du Bois and Alain Locke came through the universe."

Sarah Keys v. Carolina Coach Company, 64 MCC 769 (1955) is a landmark civil rights case in the United States in which the Interstate Commerce Commission, in response to a bus segregation complaint filed in 1953 by a Women's Army Corps (WAC) private named Sarah Louise Keys, broke with its historic adherence to the Plessy v. Ferguson separate but equal doctrine and interpreted the non-discrimination language of the Interstate Commerce Act as banning the segregation of black passengers in buses traveling across state lines.

Harriet Gibbs Marshall was an American pianist, writer, and educator of music. She is best known for opening the Washington Conservatory of Music and School of Expression in 1903 in Washington, D.C.

Anna E. Cooper was a Liberian educator, she was the first female dean of the University of Liberia.

Lula Vashti Turley Murphy was an American educator and community leader, one of the founding members of Delta Sigma Theta, the historically black sorority.

Lois Towles was an American classical pianist, music educator, and community activist. Born in Texarkana, Arkansas, she grew up in the town straddling the Arkansas and Texas line. From an early age, she was interested in music and began piano lessons at age 9. After graduating as valedictorian of her high school class, she obtained a bachelor's degree from Wiley College in Marshall, Texas, and worked as a high school teacher from 1936 to 1941. In 1942, Towles enrolled in the University of Iowa and earned two master's degrees in 1943. She went on to further her education at Juilliard, the University of California, Berkeley, the Conservatoire de Paris, and the American Conservatory at Fountainebleau.

Vivian Eileen Scott (1926–2010) was an American classical pianist and music educator. After obtaining an undergraduate degree from Howard University and a master's degree from Juilliard, she performed with distinction internationally throughout the 1950s. She was also involved in the desegregation of the Girl Scouts of the United States of America.

Mary Dudley, known as Mary Dee, was an American disc jockey who is widely considered the first African-American woman disc jockey in the United States. She grew up in Homestead, Pennsylvania, and then studied at Howard University for two years. After having her family, she attended Si Mann School of Radio in Pittsburgh, and on August 1, 1948, went on the air at WHOD radio. Gaining national attention, Dee broadcast from a storefront, "Studio Dee", in the Hill District of Pittsburgh from 1951 to 1956. She moved her show, Movin' Around with Mary Dee, to Baltimore and broadcast from station WSID from 1956 to 1958. In 1958, she moved to Philadelphia and hosted Songs of Faith on WHAT until her death in 1964.

Alyce Chenault Gullattee was an American psychiatrist, medical school professor, activist, and expert on addiction. She was a faculty member in the psychiatry department at Howard University College of Medicine for over fifty years.

Edwina Kruse was an American educator, born in Puerto Rico. She was principal of Howard High School in Wilmington, Delaware for almost 40 years, and a close associate of Alice Dunbar-Nelson, who taught at Howard.

Grace Baxter Fenderson was an American educator and clubwoman based in Newark, New Jersey. A teacher at Monmouth Street School in Newark for over 40 years, Fenderson was a co-founder of the Newark chapter of the NAACP and served as president of the Lincoln-Douglass Memorial Association. In 1959, Fenderson received the Sojourner Truth Award from the New Jersey chapter of the National Association of Negro Business and Professional Women's Clubs (NANBPWC).

Helen Hale TuckCohron was an American educator, clubwoman, and college dean. She was acting Dean of Women at Howard University from 1919 to 1922, and an active clubwoman in Harlem in the 1930s and 1940s.

Pauline Weeden Maloney, born Margaret Pauline Fletcher, was an American educator based in Lynchburg, Virginia. She was the third national president of The Links, and rector of Norfolk State University.

Madree Penn White was an American editor, educator, businesswoman and suffragist. She was one of the founders of Delta Sigma Theta, and the sorority's second president.

Eliza Pearl Shippen was an American educator, and one of the founding members of Delta Sigma Theta. She was an English professor and Dean of Women at University of the District of Columbia.

Othello Maria Harris-Jefferson was an American educator and activist from Texas. From 1929 to the 1960s, she taught at Bluefield State Teachers College in West Virginia, where the Othello Harris-Jefferson Student Center is named in her honor.

Susan "Susie" Russell Quander was an American educator, churchworker, and clubwoman. She worked with Carter G. Woodson and Charles H. Wesley on running the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH) and coordinating Negro History Week events across the United States.

References

- ↑ Fund, Julius Rosenwald (1940). "Review for the Two-year Period".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Boyd, Herb (August 22, 2019). "Dr. Margaret Just Butcher, Educator and Political Activist". Amsterdam News. p. 1. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- 1 2 3 Barnes, Paula C. (1993). "Butcher, Margaret Just". In Hine, Darlene Clark; Brown, Elsa Barkley; Terborg-Penn, Rosalyn (eds.). Black Women in America: An Historical Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. Brooklyn, New york: Carlson Publishing Inc. pp. 207. ISBN 0926019619.

- 1 2 "Margaret Butcher, Capital Teacher Gets Defense Post". Waco Tribune-Herald. August 17, 1952. p. 27. Retrieved February 15, 2020– via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 "Howard U. Prof. Hailed In Europe". The Pittsburgh Courier. July 22, 1950. p. 6. Retrieved February 14, 2020– via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Educator to Talk at Central State". The Journal Herald. March 26, 1954. p. 2. Retrieved February 14, 2020– via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Morocco Teacher to Speak". The Akron Beacon Journal. December 1, 1962. p. 9. Retrieved February 17, 2020– via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Morch, Albert (August 30, 1974). "Prince Here for Sailing Competition". The San Francisco Examiner. p. 26. Retrieved February 17, 2020– via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "CLA News". CLA Journal. 12 (2): 178. 1968. ISSN 0007-8549. JSTOR 44321495.

- ↑ "Howard U. Prof. On D.C. Board". The Pittsburgh Courier. June 27, 1953. p. 10. Retrieved February 16, 2020– via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "New D.C. School Board Appointee a Fighter!". The Pittsburgh Courier. January 9, 1954. p. 4. Retrieved February 16, 2020– via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 Hamilton, Mildred (September 3, 1974). "A Lifelong Opponent of Injustice". The San Francisco Examiner. p. 23. Retrieved February 16, 2020– via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Cover: Margaret Just Butcher Biographical Note". Negro History Bulletin. 20 (1): 15. 1956. ISSN 0028-2529. JSTOR 44215203.

- ↑ "Negroes' Battle to Be Continued". The Greenville News. April 6, 1954. p. 16. Retrieved February 16, 2020– via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "U.S. Capital School Directors Outline Anti-Segregation Policy, But Delay Action". The Morning Call. May 26, 1954. p. 10. Retrieved February 16, 2020– via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Rivera, Jr., A. M. (November 6, 1954). "NAAWP Seeking Ouster". The Pittsburgh Courier. p. 13. Retrieved February 16, 2020– via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "NAACP Member Criticizes [sic] DC School Superintendent". The Times and Democrat. November 20, 1954. p. 5. Retrieved February 16, 2020– via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Professor is Speaker for NAACP Unit". Daily Press. November 7, 1954. p. 33. Retrieved February 16, 2020– via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Segregation Remains in D.C. Schools Says Dr. Butcher". The Pittsburgh Courier. January 15, 1955. p. 3. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ↑ Blackwell, Lee (January 8, 1955). "1954 in Review". The New York Age. p. 9. Retrieved February 16, 2020– via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Dr. Margaret Butcher of D.C. is Honored by Nat'l Sorority". Alabama Tribune. December 3, 1954. p. 4. Retrieved February 16, 2020– via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Dr. Margaret Just Butcher asso-". Honolulu Star-Bulletin. July 16, 1952. p. 11. Retrieved February 14, 2020– via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ "Replaces Mrs. Bethune". The Pittsburgh Courier. June 28, 1952. p. 2. Retrieved February 17, 2020– via Newspapers.com.

- 1 2 3 Boyd, Herb (August 22, 2019). "Dr. Margaret Just Butcher, Educator and Political Activist". New York Amsterdam News. p. 2. Archived from the original on February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 16, 2020.

- ↑ "Dr. Margaret J. Butcher, Star Professor of Eng-". The Pittsburgh Courier. December 25, 1971. p. 11. Retrieved February 17, 2020– via Newspapers.com.

- ↑ Winslow, Henry F. (December 1956). "Mosaic Vision". The Crisis. 63 (10): 633–634.

- ↑ Peterson, Bernard L. (1990). Early Black American Playwrights and Dramatic Writers: A Biographical Directory and Catalog of Plays, Films, and Broadcasting Scripts. New York: Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 48. ISBN 978-0-313-26621-8.

- ↑ "Margaret J. Butcher Seeks Divorce from Hubby". Jet. 16 (5): 13. May 28, 1959.