Life

Origin and the palace coups of 944

Marianos was the eldest son of the general Leo Argyros, active in the first decades of the 10th century. He had a brother, Romanos Argyros, who in 921 married Agathe, a daughter of Emperor Romanos I Lekapenos (r. 920–944). The Argyroi therefore were counted among the firmest supporters of the Lekapenos regime. [1] Romanos Lekapenos had risen to power in 919 as regent over the young Constantine VII Porphyrogennetos (r. 913–959), whom he married to his daughter Helena. By December 920, his position had become so unassailable that he was crowned senior emperor. [2] To consolidate his hold on power, and possibly aiming to supplant the ruling Macedonian dynasty with his own family, Romanos raised his eldest son Christopher to co-emperor in 921, while the younger sons Stephen and Constantine were proclaimed co-emperors in 924. [3] Christopher died in 931, and as Constantine VII remained sidelined, Stephen and Constantine assumed an increased prominence, although formally they still ranked after their brother-in-law in the college of emperors. [4] However, in 943, the elderly Romanos drafted a will which would leave Constantine VII as the senior emperor following his death. This greatly upset his two sons, who started planning to seize power through a coup d'état, with Stephen apparently the ringleader and Constantine a rather reluctant partner. [5]

It is in this context that Marianos Argyros is first mentioned in December 944. At the time, he was a monk, and a confidant of Stephen Lekapenos. [6] According to the 11th-century historian John Skylitzes, he had earlier been honoured and trusted by Romanos. Marianos nevertheless was one of the conspirators, men such as Basil Peteinos and Manuel Kourtikes, who supported the coup of the Lekapenoi brothers on 20 December, which successfully deposed Romanos and exiled him to a monastery on the island of Prote. [7] [8] [6] A few weeks later, however, with the support of the populace, Constantine VII managed to sideline the Lekapenoi, who joined their father in exile. [9] It appears that Marianos had changed sides in time, for he participated in the arrest of the Lekapenoi. As a reward, Constantine VII, now sole ruler, freed him of his monastic vows and raised him to the rank of patrikios and the post of Count of the Stable. [6] [10] His abandonment of the monastic habit earned him the nickname "Apambas" or "Apabbas" (Ἄπαμβας/Ἀπαββᾶς), whose etymology is unclear. [6] [11]

Command in southern Italy

Marianos then disappears from the scene until he was sent at the head of troops from the themes of Macedonia and Thrace in an expedition to southern Italy, dated by modern scholars to 955. A rebellion that had broken out in the local Byzantine themes of Langobardia and Calabria, involving also the imperial vassal city-state of Naples. The Byzantine expeditionary force encircled and besieged Naples, until the city surrendered. [6] Marianos then took over the governance of the Byzantine provinces of Italy: in 956, he is attested as strategos (governor) of Calabria and Langobardia in a charter of privilege for the monastery of Monte Cassino. [6] At about the same time, following a Fatimid raid on Almeria, war had broken out between the Fatimids and the Umayyad Caliphate of Cordoba. Fatimid sources report that the Umayyads proposed joint action with Byzantium, but Marianos appears to have been focused on suppressing the rebellion rather than engaging in war with the Fatimids. Byzantine envoys even went to the Fatimid caliph, al-Mu'izz, and offered to renew and extend the existing truce. Al-Mu'izz however, determined to expose the Umayyads' collaboration with the infidel enemy and emulate the achievements of his father, refused. [6] [12] [13]

The Caliph dispatched new forces to Sicily under Ammar ibn Ali al-Kalbi and his brother al-Hasan ibn Ali al-Kalbi. In spring/summer 956, the Fatimid fleet clashed with and defeated the Byzantine fleet in two battles in the Straits of Messina, followed by Fatimid raids on the Calabrian coast. In the aftermath of these raids, Marianos travelled to the Fatimid court in person, and sought a truce in exchange for the resumption of a payment of tribute and the annual release of prisoners of war taken in the East. Al-Mu'izz agreed to these terms, but warfare resumed soon after, when the Byzantine admiral Basil destroyed the mosque built by the Fatimids at Rhegion and raided Termini. Marianos therefore returned to the Fatimid court in a second embassy in 957, going first through Sicily, where he apparently delivered to the local Fatimid governor, Ahmad ibn al-Hasan al-Kalbi, the agreed tribute. During the reception by al-Mu'izz, Marianos presented a letter by Constantine VII confirming the terms agreed during the first embassy, but this time al-Mu'izz rejected the terms. As a result of the breakdown in these negotiations, Constantine VII sent a massive expedition to Italy under admirals Krambeas and Moroleon, while Marianos commanded the land troops. The Fatimids, under the Kalbid brothers, al-Hasan and Ammar, were victorious over Marianos, but following the arrival of the Byzantine reinforcements the Fatimid fleet left Calabria, only to suffer a shipwreck on its return to Sicily. [6] [14] Marianos is no longer mentioned in Italy after that, although he may have led a third embassy to al-Mu'izz in September 958, which led to the conclusion of a five-year truce between the two powers. [6] [15]

Command in the Balkans and death

In ca. 959/961, he defeated a raid by the Magyars into Thrace, taking many of them prisoner. [6] In connection with this operation, Theophanes Continuatus refers to him as " monostrategos of the theme of Macedonia and katepano of the West", a position equivalent to that of the Domestic of the Schools of the West, in command of all the "western" (European) troops. It is unclear, however, whether this means a permanent appointment or was an ad hoc position, i.e. as strategos of Macedonia and temporary overall commander of detachments from the other European themes. The latter is more likely, as it is documented that Leo Phokas the Younger held the post of Domestic of the West, but was fighting against the Arabs in the east at the time. [6] [10]

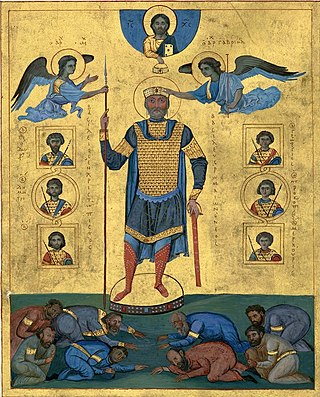

On 15 March 963, Emperor Romanos II (r. 959–963) unexpectedly died, leaving his young sons Basil II and Constantine VIII as emperors. The powerful general Nikephoros Phokas (the brother of Leo) decided to seize the throne for himself, but was opposed by the parakoimomenos (head chamberlain) and guardian of the young emperors, Joseph Bringas. Seeking support, Bringas offered Marianos the high command in the east and potentially even the throne if he would aid him. [6] [10] [16] Marianos first suggested trying to win over Nikephoros Phokas' popular nephew and lieutenant, the strategos of the Anatolic Theme, John Tzimiskes. The latter not only refused, but took his letter straight to his uncle, who summoned his armies to Caesarea and had them proclaim him emperor in early summer. [6] [16]

As Phokas' army advanced across Asia Minor on Constantinople, Marianos tried to stage a coup in Constantinople with men of the Macedonian regiments and armed prisoners of war. This move was opposed by the populace, resulting in clashes in the streets. The populace became especially enraged when Marianos tried to forcibly remove the Phokades' elderly father, Bardas, from the Hagia Sophia, where he had sought sanctuary, on 15 August. Marianos was reportedly hit on the head by a platter, thrown by a woman from a nearby house roof. Mortally wounded, he died on the next day. [6] [10] [17] Phokas' supporters rapidly prevailed thereafter. Bringas was forced to flee himself to the Hagia Sophia, and on 16 August Nikephoros Phokas was crowned senior emperor as guardian of Basil and Constantine. [18]