Related Research Articles

Evolutionary psychology is a theoretical approach in psychology that examines cognition and behavior from a modern evolutionary perspective. It seeks to identify human psychological adaptations with regards to the ancestral problems they evolved to solve. In this framework, psychological traits and mechanisms are either functional products of natural and sexual selection, non-adaptive by-products of other adaptive traits, or noise.

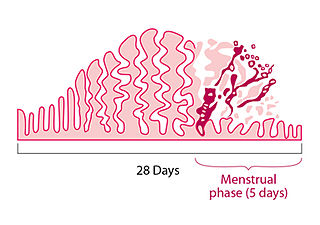

Menstruation is the regular discharge of blood and mucosal tissue from the inner lining of the uterus through the vagina. The menstrual cycle is characterized by the rise and fall of hormones. Menstruation is triggered by falling progesterone levels and is a sign that pregnancy has not occurred.

A pheromone is a secreted or excreted chemical factor that triggers a social response in members of the same species. Pheromones are chemicals capable of acting like hormones outside the body of the secreting individual, to affect the behavior of the receiving individuals. There are alarm pheromones, food trail pheromones, sex pheromones, and many others that affect behavior or physiology. Pheromones are used by many organisms, from basic unicellular prokaryotes to complex multicellular eukaryotes. Their use among insects has been particularly well documented. In addition, some vertebrates, plants and ciliates communicate by using pheromones. The ecological functions and evolution of pheromones are a major topic of research in the field of chemical ecology.

Sexual attraction is attraction on the basis of sexual desire or the quality of arousing such interest. Sexual attractiveness or sex appeal is an individual's ability to attract other people sexually, and is a factor in sexual selection or mate choice. The attraction can be to the physical or other qualities or traits of a person, or to such qualities in the context where they appear. The attraction may be to a person's aesthetics, movements, voice, or smell, among other things. The attraction may be enhanced by a person's adornments, clothing, perfume or style. It can be influenced by individual genetic, psychological, or cultural factors, or to other, more amorphous qualities. Sexual attraction is also a response to another person that depends on a combination of the person possessing the traits and on the criteria of the person who is attracted.

Instinct is the inherent inclination of a living organism towards a particular complex behaviour, containing both innate (inborn) and learned elements. The simplest example of an instinctive behaviour is a fixed action pattern (FAP), in which a very short to medium length sequence of actions, without variation, are carried out in response to a corresponding clearly defined stimulus.

Concealed ovulation or hidden œstrus in a species is the lack of any perceptible change in an adult female when she is fertile and near ovulation. Some examples of perceptible changes are swelling and redness of the genitalia in baboons and bonobos, and pheromone release in the feline family. In contrast, the females of humans and a few other species that undergo hidden estrus have few external signs of fecundity, making it difficult for a mate to consciously deduce, by means of external signs only, whether or not a female is near ovulation.

Sociobiological theories of rape explore how evolutionary adaptation influences the psychology of rapists. Such theories are highly controversial, as traditional theories typically do not consider rape a behavioral adaptation. Some object to such theories on ethical, religious, political, or scientific grounds. Others argue correct knowledge of rape causes is necessary for effective preventive measures.

Menstrual synchrony, also called the McClintock effect, or the Wellesley effect, is a contested process whereby women who begin living together in close proximity would experience their menstrual cycle onsets becoming more synchronized together in time than when previously living apart. "For example, the distribution of onsets of seven female lifeguards was scattered at the beginning of the summer, but after 3 months spent together, the onset of all seven cycles fell within a 4-day period."

A psychological adaptation is a functional, cognitive or behavioral trait that benefits an organism in its environment. Psychological adaptations fall under the scope of evolved psychological mechanisms (EPMs), however, EPMs refer to a less restricted set. Psychological adaptations include only the functional traits that increase the fitness of an organism, while EPMs refer to any psychological mechanism that developed through the processes of evolution. These additional EPMs are the by-product traits of a species’ evolutionary development, as well as the vestigial traits that no longer benefit the species’ fitness. It can be difficult to tell whether a trait is vestigial or not, so some literature is more lenient and refers to vestigial traits as adaptations, even though they may no longer have adaptive functionality. For example, xenophobic attitudes and behaviors, some have claimed, appear to have certain EPM influences relating to disease aversion, however, in many environments these behaviors will have a detrimental effect on a person's fitness. The principles of psychological adaptation rely on Darwin's theory of evolution and are important to the fields of evolutionary psychology, biology, and cognitive science.

Androstenol, also known as 5α-androst-16-en-3α-ol, is a 16-androstene class steroidal pheromone and neurosteroid in humans and other mammals, notably pigs. It possesses a characteristic musk-like odor.

Stephen Marc Breedlove is the Barnett Rosenberg professor of Neuroscience at Michigan State University in East Lansing, Michigan. He was born and raised in the Ozarks of southwestern Missouri. After graduating from Central High School in 1972, he earned a bachelor's degree in Psychology from Yale University in 1976, and a Ph.D. in psychology from UCLA in 1982. He was a professor of psychology at the University of California, Berkeley from 1982 to 2003, moving to Michigan State in 2001. He works in the fields of Behavioral Neuroscience and Neuroendocrinology. He is a member of the Society for Neuroscience and the Society for Behavioral Neuroendocrinology, and a fellow of the Association for Psychological Science (APS) and the Biological Sciences section of the American Association for the Advancement of Science (AAAS).

The Whitten effect is stimulation, by male pheromones, of synchronous estrus in a female population.

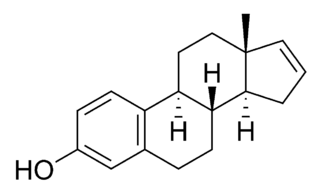

Estratetraenol, also known as estra-1,3,5(10),16-tetraen-3-ol, is an endogenous steroid found in women that has been described as having pheromone-like activities in primates, including humans. Estratetraenol is synthesized from androstadienone by aromatase likely in the ovaries, and is related to the estrogen sex hormones, yet has no known estrogenic effects. It was first identified from the urine of pregnant women.

Androstadienone, or androsta-4,16-dien-3-one, is a 16-androstene class endogenous steroid that has been described as having potent pheromone-like activities in humans. The compound is synthesized from androstadienol by 3β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase, and can be converted into androstenone by 5α-reductase, which can subsequently be converted into 3α-androstenol or 3β-androstenol by 3-ketosteroid reductase.

Odour is sensory stimulation of the olfactory membrane of the nose by a group of molecules. Certain body odours are connected to human sexual attraction. Humans can make use of body odour subconsciously to identify whether a potential mate will pass on favourable traits to their offspring. Body odour may provide significant cues about the genetic quality, health and reproductive success of a potential mate.

Dario Maestripieri is an Italian behavioral biologist who is known for his research and writings about biological aspects of behavior in nonhuman primates and humans. He is currently a Professor of Comparative Human Development, Evolutionary Biology, and Neurobiology at The University of Chicago.

The Great Pheromone Myth is a book on pheromones and their application to chemosensation in mammals by Richard Doty, director of the University of Pennsylvania's Smell and Taste Center in Philadelphia. Doty argues that the concept of pheromone introduced by Karlson and Lüscher is too simple for mammalian chemonsensory systems, failing to take into account learning and the context-dependence of chemosensation. In this book, he is especially critical of human pheromones, arguing that not only are there no definitive studies finding human pheromones, but that humans lack a functional vomeronasal organ to detect pheromones. Its publication received coverage in the news media, especially concerning its arguments that human pheromones do not exist.

No study has led to the isolation of true human sex pheromones, though various researchers have investigated the possibility of their existence. Sex pheromones are chemical (olfactory) signals, pheromones, released by an organism to attract an individual, encourage it to mate with it, or perform some other function closely related with sexual reproduction. While humans are highly dependent upon visual cues, when in proximity, smells also play a role in sociosexual behaviors. An inherent difficulty in studying human pheromones is the need for cleanliness and odorlessness in human participants. Experiments have focused on three classes of putative human pheromones: axillary steroids, vaginal aliphatic acids, and stimulators of the vomeronasal organ.

The ovulatory shift hypothesis holds that women experience evolutionarily adaptive changes in subconscious thoughts and behaviors related to mating during different parts of the ovulatory cycle. It suggests that what women want, in terms of men, changes throughout the menstrual cycle. Two meta-analyses published in 2014 reached opposing conclusions on whether the existing evidence was robust enough to support the prediction that women's mate preferences change across the cycle. A newer 2018 review does not show women changing the type of men they desire at different times in their fertility cycle.

Josephine Ball was an American comparative psychologist, endocrinologist, and clinical psychologist best known as an early pioneer in the study of reproductive behavior and neuroendocrinology (1920s-1940s). She later worked as a clinical psychologist in the New York State health system and at the Veteran's Administration Hospital in Perry Point, Maryland.

References

- ↑ "Martha K. McClintock: Distinguished Scientific Award for an Early Career Contribution to Psychology". American Psychologist. 38 (1): 57–60. 1983. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.38.1.57.

- ↑ Bass, E (1996). "Martha McClintock: Of mice and women". Ms. 6 (5): 31. ProQuest 204301464.

- ↑ "IMB Martha K. McClintock". 2004-03-14. Retrieved 2007-02-07.

- ↑ "Martha K. McClintock: Distinguished Scientific Award for an Early Career Contribution to Psychology". American Psychologist. 38 (1): 57–60. 1983. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.38.1.57.

- ↑ "Center for Interdisciplinary Health Disparities Research". Archived from the original on 2008-02-26. Retrieved 2008-01-03.

- ↑ McClintock, MK (1971). "Menstrual synchrony and suppression". Nature. 229 (5282): 244–5. doi:10.1038/229244a0. PMID 4994256. S2CID 4267390.

- ↑ Whitten, W (1999). "Reproductive biology: Pheromones and regulation of ovulation". Nature. 401 (6750): 232–3. doi: 10.1038/45720 . PMID 10499577. S2CID 4424785.

- ↑ Wilson, H.C. (1992). "A critical review of menstrual synchrony research". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 17 (6): 565–591. doi:10.1016/0306-4530(92)90016-z. PMID 1287678. S2CID 16011920.

- ↑ Wilson, H. C. (1987). "Female axillary secretions influence women's menstrual cycles: A critique". Hormones and Behavior. 21 (4): 536–50. doi:10.1016/0018-506x(87)90012-2. PMID 3428891. S2CID 22313169.

- ↑ Hummer, T.A.; McClintock, M.K. (2009). "Putative human pheromone androstadienone attunes the mind specifically to emotional information". Hormones and Behavior. 55 (4): 548–559. doi:10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.01.002. PMID 19470369. S2CID 17022112.

- ↑ Bass, E (1996). "Martha McClintock: Of mice and women". Ms. 6 (5): 31. ProQuest 204301464.

- ↑ "Martha McClintock – Institute for Mind and Biology at the University of Chicago".