Related Research Articles

Margaret Plantagenet, Countess of Salisbury, was the only surviving daughter of George Plantagenet, Duke of Clarence and his wife Isabel Neville. As a result of Margaret's marriage to Richard Pole, she was also known as Margaret Pole. She was one of just two women in 16th-century England to be a peeress in her own right without a husband in the House of Lords.

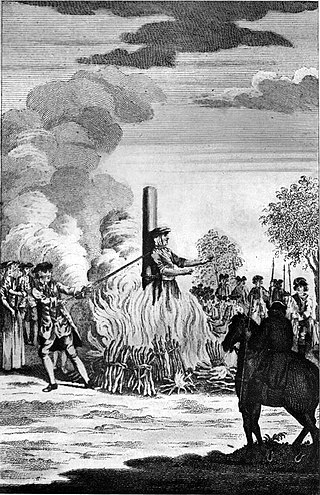

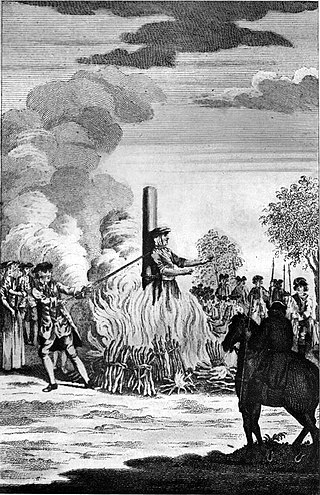

Death by burning is an execution, murder, or suicide method involving combustion or exposure to extreme heat. It has a long history as a form of public capital punishment, and many societies have employed it as a punishment for and warning against crimes such as treason, heresy, and witchcraft. The best-known execution of this type is burning at the stake, where the condemned is bound to a large wooden stake and a fire lit beneath. A holocaust is a religious animal sacrifice that is completely consumed by fire, also known as a burnt offering. The word derives from the ancient Greek holokaustos, the form of sacrifice in which the victim was reduced to ash, as distinguished from an animal sacrifice that resulted in a communal meal.

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu was an English aristocrat, medical pioneer, writer, and poet. Born in 1689, Lady Mary spent her early life in England. In 1712, Lady Mary married Edward Wortley Montagu, who later served as the British ambassador to the Sublime Porte. Lady Mary joined her husband on the Ottoman excursion, where she was to spend the next two years of her life. During her time there, Lady Mary wrote extensively on her experience as a woman in Ottoman Constantinople. After her return to England, Lady Mary devoted her attention to the upbringing of her family before dying of cancer in 1762.

Mary Toft, also spelled Tofts, was an English woman from Godalming, Surrey, who in 1726 became the subject of considerable controversy when she tricked doctors into believing that she had given birth to rabbits.

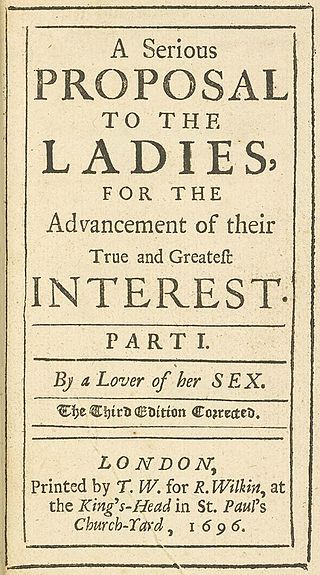

Mary Astell was an English protofeminist writer, philosopher, and rhetorician who advocated for equal educational opportunities for women. Astell is primarily remembered as one of England's inaugural advocates for women's rights and some commentators consider her to have been "the first English feminist."

Laurel Thatcher Ulrich is a Pulitzer Prize-winning American historian specializing in early America and the history of women, and a professor at Harvard University. Her approach to history has been described as a tribute to "the silent work of ordinary people". Ulrich has also been a MacArthur Genius Grant recipient. Her most famous book, A Midwife’s Tale, was later the basis for a PBS documentary film.

Martha Moore Ballard was an American midwife and healer. Unusual for the time, Ballard kept a diary with thousands of entries over nearly three decades, which has provided historians with invaluable insight into colonial frontier-women's lives.

Mariticide literally means the killing of one's own husband. It can refer to the act itself or the person who carries it out. It can also be used in the context of the killing of one's own boyfriend. In current common law terminology, it is used as a gender-neutral term for killing one's own spouse or significant other of either sex. Conversely, the killing of a wife or girlfriend is called uxoricide.

Events from the year 1687 in England.

Elizabeth Cellier, commonly known as the "Popish Midwife", was a notable Catholic midwife in seventeenth-century England. She stood trial for treason in 1679 for her alleged part in the "Meal-Tub Plot" against the future King James II, but was eventually freed. Cellier was later imprisoned for allegations made in her 1680 work Malice Defeated, in which she recounted the events of the alleged conspiracy against the future King. She later became a pamphleteer and advocated for advancements in the field of midwifery. Cellier published A Scheme for the Foundation of a Royal Hospital in 1687, where she outlined plans for a hospital and a college for instructions in midwifery, as well as proposing that midwives of London should enter into a corporation and use their fees to establish parish houses where any woman could give birth. Cellier resided in London, England until her death.

Catherine Hayes, sometimes spelled Catharine Hayes, was an English woman who was burned at the stake for committing petty treason by killing her husband.

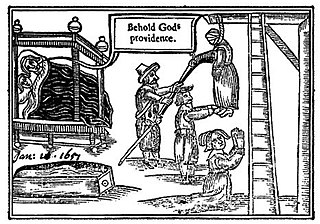

Anne Greene was an English domestic servant who was accused of committing infanticide in 1650. She is known for surviving her attempted execution by hanging, being revived by physicians from the University of Oxford.

Sidney Kennon, known as Mrs. Cannon, was an 18th-century British midwife who delivered the babies of royalty and other great families. She collected numerous creatures, curiosities and specimens. Her collections were auctioned after her death and she left a large sum of money to promote the delivery of babies by women rather than men.

Thomas Moundeford M.D. (1550–1630) was an English academic and physician, President of the London College of Physicians for three periods.

In England, death by burning was a legal punishment inflicted on women found guilty of high treason, petty treason, and heresy during the Middle Ages and Early Modern period. Over a period of several centuries, female convicts were publicly burnt at the stake, sometimes alive, for a range of activities including coining and mariticide.

Elizabeth Johnson, néeReynolds, was an English pamphleteer who attempted to win one of the rewards offered by the 1714 Longitude Act passed, which offered monetary rewards for anyone who could find a simple and practical method for the precise determination of a ship's longitude. Johnson and Jane Squire are the only two women known to have made such an attempt as it was not considered an appropriate subject for early modern women especially given its financial, maritime, and government dimensions.

The Pittenweem witches were five Scottish women accused of witchcraft in the small fishing village of Pittenweem in Fife on the east coast of Scotland in 1704. Another two women and a man were named as accomplices. Accusations made by a teenage boy, Patrick Morton, against a local woman, Beatrix Layng, led to the death in prison of Thomas Brown, and, in January 1705, the murder of Janet Cornfoot by a lynch mob in the village.

Mary Channing was an English woman from the county of Dorset. Channing is known for being convicted of poisoning her husband and being burnt at the stake.

Theodosia, Lady Ivie or Ivy (1628–1697) was an aristocratic heiress and a figure of notoriety in the east end of London in the 17th century. Famed for her “wit, beauty and cunning in law above all others,” her claims to own land stretching from Wapping to Ratcliff led to a constant stream of litigation which ran for almost 75 years. At one particular trial, presided over by Lord Chief Justice Jeffreys, evidence emerged that Ivie had presented the court with forged deeds on which she made her land claims and Jeffreys subsequently arranged for charges to be brought against her for forgery.

Mary Lakeland also known as Mother Lakeland and the “Ipswich Witch”, was an English woman executed for witchcraft in Ipswich. She belonged to the few people in England to have been executed by burning after a conviction of witchcraft. She was the last person executed for witchcraft in the town of Ipswich.

References

- ↑ Dolan 2010, p. 89.

- ↑ Capp, B. S. (2004). When Gossips Meet: Women, Family, and Neighbourhood in Early Modern England. Oxford University Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-0-19-927319-5.

- 1 2 3 Phillips, Roderick (1991). Untying the Knot: A Short History of Divorce. Cambridge University Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-0-521-42370-0.

- 1 2 3 Dolan 2010, p. 90.

- 1 2 3 Martin, Randall (2007). Women, Murder, and Equity in Early Modern England. Routledge. pp. 71–79. ISBN 978-1-135-89945-5.

- 1 2 Dolan 2010, p. 91.

- ↑ Bicks, Caroline (2017). Midwiving Subjects in Shakespeare's England. Taylor & Francis. p. 106. ISBN 978-1-351-91766-7.

- ↑ Bramston, Sir John (1845). The Autobiography of Sir John Bramston, K.B., of Skreens, in the Hundred of Chelmsford: Now First Printed from the Original Ms. in the Possession of His Lineal Descendant Thomas William Bramston, Esq., One of the Knights of the Shire for South Essex. Camden Society. p. 305.

- ↑ Granger, James (1824). A Biographical History of England, from Egbert the Great to the Revolution. W. Baynes and son. pp. 178–79.

- ↑ Smith, Alfred Russell (1878). A Catalogue of Ten Thousand Tracts and Pamphlets: And Fifty Thousand Prints and Drawings, Illustrating the Topography and Antiquities of England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland. Collected During the Last Thirty-five Years by the Late William Upcott and John Russell Smith. Now Offered for Sale ... p. 240.

- ↑ Banerjee 2016, p. 158.

- ↑ Banerjee 2016, p. 187.