Related Research Articles

Gnosticism is a collection of ancient religious ideas and systems which originated in the first century AD among early Christian and Jewish sects. These various groups emphasised personal spiritual knowledge (gnosis) over orthodox teachings, traditions, and the authority of the church. Viewing material existence as flawed or evil, Gnostic cosmogony generally presents a distinction between a supreme, hidden God and a malevolent lesser divinity who is responsible for creating the material universe. Gnostics considered the principal element of salvation to be direct knowledge of the supreme divinity in the form of mystical or esoteric insight. Many Gnostic texts deal not in concepts of sin and repentance, but with illusion and enlightenment.

Irenaeus was a Greek bishop noted for his role in guiding and expanding Christian communities in what is now the south of France and, more widely, for the development of Christian theology by combating heresy and defining orthodoxy. Originating from Smyrna, now Izmir in Turkey, he had seen and heard the preaching of Polycarp, the last known living connection with the Apostles, who in turn was said to have heard John the Evangelist.

In Christianity, Sabellianism is the eastern Church heresy equivalent to the western historic Patripassianism, which are both forms of theological modalism. Sabellianism is the belief that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit are three different modes or aspects of God, as opposed to a Trinitarian view of three distinct persons within the Godhead. The term Sabellianism comes from Sabellius, who was a theologian and priest from the 3rd century. None of his writings have survived and so all that is known about him comes from his opponents. All evidence shows that Sabellius held Jesus to be deity while denying the plurality of persons in God and holding a belief similar to modalistic monarchianism. Modalistic monarchianism has been generally understood to have arisen during the second and third centuries, and to have been regarded as heresy after the fourth, although this is disputed by some.

John Badby, one of the early Lollard martyrs, was a tailor in the west Midlands, and was condemned by the Worcester diocesan court for his denial of transubstantiation.

Edward Wightman was an English radical Anabaptist, executed at Lichfield on charges of heresy. He was the last person to be burned at the stake in England for heresy.

Word of Faith is a worldwide Evangelical Christian movement which teaches that Christians can access the power of faith through speech. Its teachings are found on radio, the internet, television, and in many Charismatic denominations and communities. The movement renounces poverty and physical suffering as either necessary to a godly life or glorifying Jesus Christ. It teaches that the salvation won by Jesus on the cross included wealth and prosperity for believers.

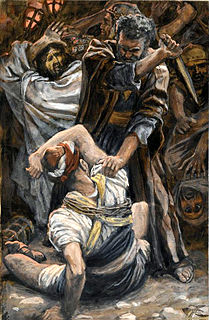

Malchus was the servant of the Jewish High Priest Caiaphas who participated in the arrest of Jesus as written in the four gospels. According to the Bible, one of the disciples, Simon Peter, being armed with a sword, cut off the servant's ear in an attempt to prevent the arrest of Jesus.

Terebinthus was a suggested pupil of Scythianus, during the 1st-2nd century AD, according to the writings of Christian writer and anti-Manichaean polemicist Cyril of Jerusalem, and is mentioned earlier in the anonymously written, critical biography of Mani known as Acta Archelai.

Cyril of Jerusalem

Apostasy in Christianity is the rejection of Christianity by someone who formerly was a Christian. The term apostasy comes from the Greek word apostasia ("ἀποστασία") meaning defection, departure, revolt or rebellion. It has been described as "a willful falling away from, or rebellion against, Christianity. Apostasy is the rejection of Christ by one who has been a Christian...." "Apostasy is a theological category describing those who have voluntarily and consciously abandoned their faith in the God of the covenant, who manifests himself most completely in Jesus Christ." "Apostasy is the antonym of conversion; it is deconversion."

Subordinationism is a belief that began within early Christianity that asserts that the Son and the Holy Spirit are subordinate to God the Father in nature and being. Various forms of subordinationism were believed or condemned until the mid-4th century, when the debate was decided against subordinationism as an element of the Arian controversy. In 381, after many decades of formulating the doctrine of the Trinity, the First Council of Constantinople condemned Arianism.

Heresy in Christianity denotes the formal denial or doubt of a core doctrine of the Christian faith as defined by one or more of the Christian churches.

The doctrine of the Trinity, considered the core of Christian theology by Trinitarians, is the result of continuous exploration by the church of the biblical data, thrashed out in debate and treatises, eventually formulated at the First Council of Nicaea in AD 325 in a way they believe is consistent with the biblical witness, and further refined in later councils and writings. The most widely recognized Biblical foundations for the doctrine's formulation are in the Gospel of John.

Francis Kett was an Anglican clergyman burned for heresy.

Edmund Freke was an English dean and bishop.

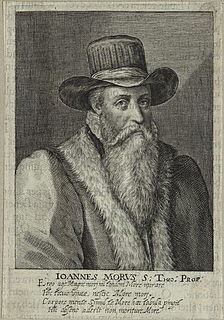

John More was an English clergyman, known as the 'Apostle of Norwich.' Tending to nonconformity, he was treated leniently by the church authorities.

William Burton was an English clergyman, known for his writings, an insider's view of the Puritan ascendancy at Norwich, and as an eyewitness to heresy executions.

Epikoros is a Jewish term cited in the Mishnah, referring to one who does not have a share in the world to come due to his casting off of the yoke of God and his commandments:

"All Israel have a share in the world to come as states: Your people are all righteous, they shall inherit the land for ever, the branch of My planting, the work of My hands, wherein I glory. And these are the ones who do not have a portion in the world to come: He who maintains that there is no resurrection of the dead derived from the Torah, and [He who maintains] that the Torah is not from the Heavens, and an Epikoros"

Heresy in the Catholic Church denotes the formal denial or doubt of a core doctrine of the Roman Catholic Church. Heresy has a very specific meaning in the Catholic Church and there are four elements which constitute formal heresy; a valid Christian baptism; a profession of still being a Christian; outright denial or positive doubt regarding a truth that the Catholic Church regards as revealed by God; and lastly, the disbelief must be morally culpable, that is, there must be a refusal to accept what is known to be a doctrinal imperative. Therefore, to become a heretic in the strict canonical sense and be excommunicated, one must deny or question a truth that is taught as the word of God, and at the same time recognize one's obligation to believe it. If the person is believed to have acted in good faith, as one might out of ignorance, then the heresy is only material and implies neither guilt nor sin against faith.

Malachi 4 is the fourth chapter of the Book of Malachi in the Hebrew Bible or the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. This book contains the prophecies attributed to the prophet Malachi, and is a part of the Book of the Twelve Minor Prophets.

References

- ↑ Mathew Carey Letters on religious persecution 1829 "Matthew Hamont, of Hetharset, three miles from Norwich, was "convicted before the Bishop of Norwich, for that he denied Christ to be our Saviour."

- ↑ Henry Martyn Dexter, Morton Dexter (1905). The England and Holland of the Pilgrims. Houghton, Mifflin. p. 140.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Gordon, Alexander (1885–1900). . Dictionary of National Biography . London: Smith, Elder & Co.

- ↑ "Jonathan Miller's 'A Short History of Disbelief'". secularsites.freeuk.com. Archived from the original on 11 February 2014. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- Attribution

![]()