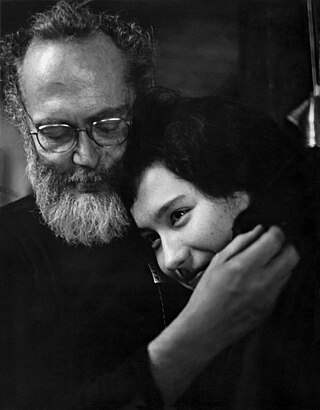

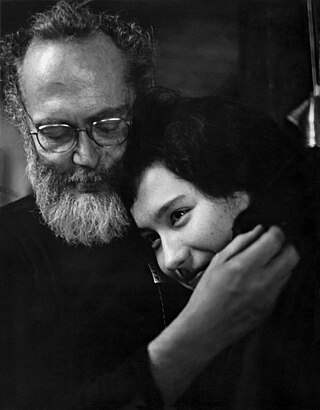

William Eugene Smith was an American photojournalist. He has been described as "perhaps the single most important American photographer in the development of the editorial photo essay." His major photo essays include World War II photographs, the visual stories of an American country doctor and a nurse midwife, the clinic of Albert Schweitzer in French Equatorial Africa, the city of Pittsburgh, and the pollution which damaged the health of the residents of Minamata in Japan. His 1948 series, Country Doctor, photographed for Life, is now recognized as "the first extended editorial photo story".

The Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) is a public medical school in Charleston, South Carolina. It opened in 1824 as a small private college aimed at training physicians and has since established hospitals and medical facilities across the state. It is one of the oldest continually operating schools of medicine in the United States and the oldest in the Deep South.

Nurse education consists of the theoretical and practical training provided to nurses with the purpose to prepare them for their duties as nursing care professionals. This education is provided to student nurses by experienced nurses and other medical professionals who have qualified or experienced for educational tasks, traditionally in a type of professional school known as a nursing school of college of nursing. Most countries offer nurse education courses that can be relevant to general nursing or to specialized areas including mental health nursing, pediatric nursing, and post-operative nursing. Nurse education also provides post-qualification courses in specialist subjects within nursing.

The Frontier Nursing Service (FNS) provides healthcare services to rural, underserved populations since 1925, and educates nurse-midwives since 1939.

Mary Carson Breckinridge was an American nurse midwife and the founder of the Frontier Nursing Service (FNS), which provided comprehensive family medical care to the mountain people of rural Kentucky. FNS served remote and impoverished areas off the road and rail system but accessible by horseback. She modeled her services on European practices and sought to professionalize American nurse-midwives to practice autonomously in homes and decentralized clinics. Although Breckinridge's work demonstrated efficacy by dramatically reducing infant and maternal mortality in Appalachia, at a comparatively low cost, her model of nurse-midwifery never took root in the United States.

Dame Mary Rosalind Paget, DBE, ARRC, was a noted British nurse, midwife and reformer. She was the first superintendent, later inspector general, of the Queen's Jubilee Institute for District Nursing, which was renamed as the Queen's Institute of District Nursing in 1928 and as the Queen's Nursing Institute in 1973.

A monthly nurse is a woman who looks after a mother and her baby during the postpartum or postnatal period. The phrase is now largely obsolete, but the role is still performed under other names and conditions worldwide.

Ruth Watson Lubic, CNM, EdD, FAAN, FACNM, is an American nurse-midwife and applied anthropologist who pioneered the role of nurse-midwives as primary care providers for women, particularly in maternity care. Lubic is considered to be one of the leaders of the nurse-midwifery movement in the United States.

In the United States, certified nurse midwives (CNMs) are advanced practice registered nurses in nurse midwifery, the nursing care of women during pregnancy and the postpartum period. CNMs are considered as midwives.

Midwives in the United States assist childbearing women during pregnancy, labor and birth, and the postpartum period. Some midwives also provide primary care for women including well-woman exams, health promotion, and disease prevention, family planning options, and care for common gynecological concerns. Before the turn of the 20th century, traditional midwives were informally trained and helped deliver almost all births. Today, midwives are professionals who must undergo formal training. Midwives in the United States formed the Midwifery Education, Regulation, and Association task force to establish a framework for midwifery.

Mary Francis Hill Coley was an American lay midwife who ran a successful business providing a range of birth services and who starred in a critically acclaimed documentary film used to train midwives and doctors. Her competence projected an image of black midwives as the face of an internationally esteemed medical profession, while working within the context of deep social and economic inequality in health care provided to African Americans. Her life story and work exist in the context of Southern granny midwives who served birthing women outside of hospitals.

A midwife is a health professional who cares for mothers and newborns around childbirth, a specialization known as midwifery.

Victoria Joyce Ely was an American nurse who served in World War I in the Army Nurse Corps and then provided nursing services in the Florida Panhandle in affiliation with the American Red Cross. To address the high infant and maternal death rates in Florida in the 1920s, she lectured and worked at the state health office. Due to her work, training improved for birth attendants and death rates dropped. After 15 years in the state's service, she opened a rural health clinic in Ruskin, Florida, providing both basic nursing services and midwife care. The facility was renamed the Joyce Ely Health Center in her honor in 1954. In 1983, she was inducted into Florida Public Health Association's Hall of Memory and in 2002 was inducted into the Florida Women's Hall of Fame.

Angela Murdaugh is an American Catholic religious sister in the Franciscan Sisters of Mary, a Certified Nurse‐Midwife. She was a pioneer in promoting nurse midwives and birth centers. Out of this passion, she founded the Holy Family Birth Center in Weslaco, TX in 1983.

Margaret Charles Smith was an African-American midwife, who became known for her extraordinary skill over a long career, spanning over thirty years. Despite working primarily in rural areas with women who were often in poor health, she lost very few of the more than 3000 babies she delivered, and none of the mothers in childbirth. In 1949, she became one of the first official midwives in Green County, Alabama, and she was still practicing in 1976, when the state passed a law outlawing traditional midwifery. In the 1990s, she cowrote a book about her career, Listen to Me Good: The Life Story of an Alabama Midwife, and in 2010 she was inducted into the Alabama Women's Hall of Fame.

Mary Lee Mills was an American nurse. Born into a family of eleven children, she attended the Lincoln Hospital School of Nursing and graduated in a nursing degree and became a registered nurse. After working as a midwife, she joined the United States Public Health Service (USPHS) in 1946 and served as their chief nursing officer of Liberia, working to hold some of their first campaigns in public health education. Mills later worked in Lebanon and established the country's first nursing school, and helped to combat treatable diseases. She was later assigned to South Vietnam, Cambodia and Chad to provide medical education.

Eunice Katherine Macdonald "Kitty" Ernst was an American nurse midwife and leader in the nurse-midwife movement in the United States.

Mamie Odessa Hale was a leader in public health and a midwife consultant who worked in Arkansas for the Department of Health from 1945 to 1950. During this time, Hale's objective was to educate and train 'granny midwives.' Her efforts were in place to address the public health disparity between black and white women that was currently evident.

Elizabeth Sager Sharp CNM, DrPH, FAAN, FACNM, was an American nurse and midwife who specialized in maternal and newborn health. In 1999, she received the American College of Nurse-Midwives' Hattie Hemschemeyer Award.