Related Research Articles

Samizdat was a form of dissident activity across the Eastern Bloc in which individuals reproduced censored and underground makeshift publications, often by hand, and passed the documents from reader to reader. The practice of manual reproduction was widespread, because typewriters and printing devices required official registration and permission to access. This was a grassroots practice used to evade official Soviet censorship.

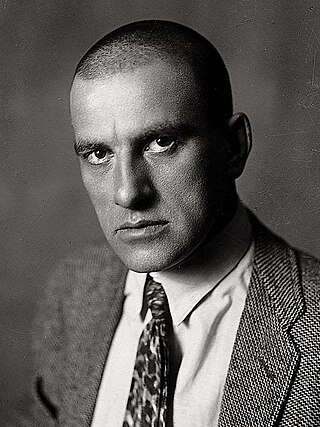

Vladimir Vladimirovich Mayakovsky was a Soviet Russian poet, playwright, artist, and actor. During his early, pre-Revolution period leading into 1917, Mayakovsky became renowned as a prominent figure of the Russian Futurist movement. He co-signed the Futurist manifesto, A Slap in the Face of Public Taste (1913), and wrote such poems as "A Cloud in Trousers" (1915) and "Backbone Flute" (1916). Mayakovsky produced a large and diverse body of work during the course of his career: he wrote poems, wrote and directed plays, appeared in films, edited the art journal LEF, and produced agitprop posters in support of the Communist Party during the Russian Civil War of 1917–1922.

Vladimir Konstantinovich Bukovsky was a Russian-born British human rights activist and writer. From the late 1950s to the mid-1970s, he was a prominent figure in the Soviet dissident movement, well known at home and abroad. He spent a total of twelve years in the psychiatric prison-hospitals, labour camps, and prisons of the Soviet Union during Brezhnev rule.

Yuri Timofeyevich Galanskov was a Russian poet, historian, human rights activist and dissident. For his political activities, such as founding and editing samizdat almanac Phoenix, he was incarcerated in prisons, camps and forced treatment psychiatric hospitals (Psikhushkas). He died in a labor camp.

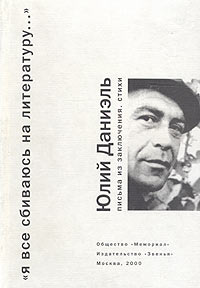

Yuli Markovich Daniel was a Russian writer and Soviet dissident known as a defendant in the Sinyavsky–Daniel trial in 1966.

Edward Samoilovich Kuznetsov is a Soviet-Israeli dissident, refusenik, journalist, and writer. One of the leaders of the 1970 Dymshits–Kuznetsov hijacking affair, Kuznetsov's case drew international attention following his death sentence. As a result of global protests, his sentence was commuted to fifteen years' imprisonment.

Alexander Sergeyevich Esenin-Volpin was a Russian-American poet and mathematician.

Natalya Yevgenyevna Gorbanevskaya was a Russian poet, a translator of Polish literature and a civil-rights activist. She was one of the founders and the first editor of A Chronicle of Current Events (1968–1982). On 25 August 1968, with seven others, she took part in the 1968 Red Square demonstration against the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. In 1970 a Soviet court sentenced Gorbanevskaya to incarceration in a psychiatric hospital. She was released from the Kazan Special Psychiatric Hospital in 1972, and emigrated from the USSR in 1975, settling in France. In 2005, she became a citizen of Poland.

They Chose Freedom is a four-part TV documentary on the history of political dissent in the USSR from the 1950s to the 1990s. It was produced in 2005 by Vladimir Kara-Murza.

Soviet dissidents were people who disagreed with certain features of Soviet ideology or with its entirety and who were willing to speak out against them. The term dissident was used in the Soviet Union (USSR) in the period from the mid-1960s until the Fall of Communism. It was used to refer to small groups of marginalized intellectuals whose challenges, from modest to radical to the Soviet regime, met protection and encouragement from correspondents, and typically criminal prosecution or other forms of silencing by the authorities. Following the etymology of the term, a dissident is considered to "sit apart" from the regime. As dissenters began self-identifying as dissidents, the term came to refer to an individual whose non-conformism was perceived to be for the good of a society. The most influential subset of the dissidents is known as the Soviet human rights movement.

Vadim Nikolaevich Delaunay was a Soviet poet and dissident, who participated in the 1968 Red Square demonstration of protest against military suppression of the Prague Spring.

The 1968 Red Square demonstration took place in Moscow on 25 August 1968. It was a protest by eight demonstrators against the invasion of Czechoslovakia on the night of 20–21 August 1968 by the Soviet Union and its Warsaw Pact allies, crushing the Prague Spring, the challenge to centralised planning and censorship by communist leader Alexander Dubček.

Lyudmila Mikhaylovna Alexeyeva was a Russian historian and human-rights activist who was a founding member in 1976 of the Moscow Helsinki Watch Group and one of the last Soviet dissidents active in post-Soviet Russia.

The glasnost meeting, also known as the glasnost rally, was the first spontaneous public political demonstration in the Soviet Union after the Second World War. It took place in Moscow on 5 December 1965 as a response to the trial of writers Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel. The demonstration is considered to mark the beginning of a movement for civil rights in the Soviet Union.

SMOG was one of the earliest informal literary groups independent of the Soviet state in the post-Stalin Soviet Union. Among several interpretations of the acronym are Smelost', Mysl', Obraz i Glubina, and, humorously, Samoe Molodoe Obshchestvo Geniev. It is also a pun: the Russian word "смог" means "<he> was able ".

The Dubravny Camp, Special Camp No.3, commonly known as the Dubravlag, was a Gulag labor camp of the Soviet Union located in Yavas, Mordovia from 1948 to 2005.

Campaign Against Psychiatric Abuse was a group that was founded by Soviet dissident Viktor Fainberg in April 1975 and participated in the struggle against political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union from 1975 to 1988.

In 1965 a human rights movement emerged in the USSR. Those actively involved did not share a single set of beliefs. Many wanted a variety of civil rights — freedom of expression, of religious belief, of national self-determination. To some it was crucial to provide a truthful record of what was happening in the country, not the heavily censored version provided in official media outlets. Others still were "reform Communists" who thought it possible to change the Soviet system for the better.

The Trial of the Four, also Galanskov–Ginzburg trial, was the 1968 trial of Yuri Galanskov, Alexander Ginzburg, Alexey Dobrovolsky and Vera Lahkova for their involvement in samizdat publications. The trial took place in Moscow City Court on January 8–12. All four defendants were sentenced to terms in labour camps. The trial played a major part in consolidating the emerging human rights movement in the Soviet Union.

Vladimir Nikolaevich Osipov was a Russian writer who founded the Soviet samizdat journal Veche (Assembly). The journal is considered to be an important document of the nationalist or Slavophile strand within the Soviet dissident movement.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bukovskii (1978). To build a castle: my life as a dissenter. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 Sundaram, Chantal (2006). ""The stone skin of the monument": Mayakovsky, Dissent and Popular Culture in the Soviet Union". Toronto Slavic Quarterly (16).

- ↑ Volgin, Igor (1997). "Na Ploshchadi Mayakovskogo materiaizovalos' vremya". In Polikovskaia, Liudmila (ed.). My predchuvstvie… predtecha…. Zveniia. (Google Books)

- 1 2 3 4 5 Alexeyeva, Lyudmila (1987). Soviet Dissent: Contemporary Movements for National, Religious, and Human Rights. John Glad, Carol Pearce (trans.). Middletown, Conn.: Wesleyan University Press. ISBN 0-8195-6176-2.

- 1 2 3 Boobbyer, Philip (2005). Conscience, Dissent and Reform in Soviet Russia. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Boris Kagarlitsky, The Thinking Reed: Intellectuals and the Soviet State from 1917 to the Present, London and New York, 1988, p. 147.

- ↑ Mikhail Kheifets, “Russkii patriot Vladimir Osipov,” Kontinent, 1981, No. 27, pp.159-212 (p.176)

- 1 2 Batshev, Vladimir (1997). "Oni peredali nam svoii opyt". In Polikovskaia, Liudmila (ed.). My predchuvstvie… predtecha…. Moskva: Zvenia. ISBN 9785787000023.

- ↑ Gozzi, Laura (2023-12-28). "Russian poets get jail sentences for anti-war poetry reading". BBC News . Retrieved 2023-12-28.

- ↑ VICE News (2024-03-09). Putin's Russia: A Country at War with Itself . Retrieved 2024-08-04– via YouTube.