Colonialism is the pursuing, establishing and maintaining of control and exploitation of people and of resources by a foreign group. Colonizers monopolize political power and hold conquered societies and their people to be inferior to their conquerors in legal, administrative, social, cultural, or biological terms. While frequently advanced as an imperialist regime, colonialism can also take the form of settler colonialism, whereby colonial settlers invade and occupy territory to permanently replace an existing society with that of the colonizers, possibly towards a genocide of native populations.

A pandemic is an epidemic of an infectious disease that has a sudden increase in cases and spreads across a large region, for instance multiple continents or worldwide, affecting a substantial number of individuals. Widespread endemic diseases with a stable number of infected individuals such as recurrences of seasonal influenza are generally excluded as they occur simultaneously in large regions of the globe rather than being spread worldwide.

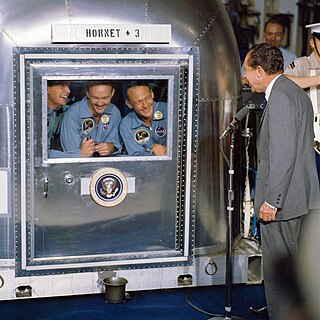

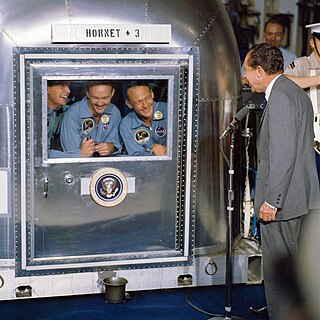

A quarantine is a restriction on the movement of people, animals, and goods which is intended to prevent the spread of disease or pests. It is often used in connection to disease and illness, preventing the movement of those who may have been exposed to a communicable disease, yet do not have a confirmed medical diagnosis. It is distinct from medical isolation, in which those confirmed to be infected with a communicable disease are isolated from the healthy population.

Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies is a 1997 transdisciplinary non-fiction book by the American author Jared Diamond. The book attempts to explain why Eurasian and North African civilizations have survived and conquered others, while arguing against the idea that Eurasian hegemony is due to any form of Eurasian intellectual, moral, or inherent genetic superiority. Diamond argues that the gaps in power and technology between human societies originate primarily in environmental differences, which are amplified by various positive feedback loops. When cultural or genetic differences have favored Eurasians, he asserts that these advantages occurred because of the influence of geography on societies and cultures and were not inherent in the Eurasian genomes.

The plague of Justinian or Justinianic plague was an epidemic that afflicted the entire Mediterranean Basin, Europe, and the Near East, severely affecting the Sasanian Empire and the Byzantine Empire, especially Constantinople. The plague is named for the Byzantine Emperor Justinian I, who according to his court historian Procopius contracted the disease and recovered in 542, at the height of the epidemic which killed about a fifth of the population in the imperial capital. The contagion arrived in Roman Egypt in 541, spread around the Mediterranean Sea until 544, and persisted in Northern Europe and the Arabian Peninsula until 549. By 543, the plague had spread to every corner of the empire. As the first episode of the first plague pandemic, it had profound economic, social, and political effects across Europe and the Near East and cultural and religious impact on Eastern Roman society.

The Columbian exchange, also known as the Columbian interchange, was the widespread transfer of plants, animals, precious metals, commodities, culture, human populations, technology, diseases, and ideas between the New World in the Western Hemisphere, and the Old World (Afro-Eurasia) in the Eastern Hemisphere, in the late 15th and following centuries. It is named after the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus and is related to the European colonization and global trade following his 1492 voyage. Some of the exchanges were purposeful while others were unintended. Communicable diseases of Old World origin resulted in an 80 to 95 percent reduction in the number of Indigenous peoples of the Americas from the 15th century onwards, most severely in the Caribbean. The cultures of both hemispheres were significantly impacted by the migration of people, both free and enslaved, from the Old World to the New. European colonists and African slaves replaced Indigenous populations across the Americas, to varying degrees. The number of Africans taken to the New World was far greater than the number of Europeans moving to the New World in the first three centuries after Columbus.

The Antonine Plague of AD 165 to 180, also known as the Plague of Galen, was a prolonged and destructive epidemic, which impacted the Roman Empire. It was possibly contracted and spread by soldiers who were returning from campaign in the Near East. Scholars generally believe the plague was smallpox, although measles has also been suggested, and recent genetic evidence strongly suggests that the most severe form of smallpox only arose in Europe much later. In AD 169 the plague may have claimed the life of the Roman emperor Lucius Verus, who was co-regnant with Marcus Aurelius. These two emperors had risen to the throne by virtue of being adopted by the previous emperor, Antoninus Pius, and as a result, their family name, Antoninus, has become associated with the pandemic.

Environmental history is the study of human interaction with the natural world over time, emphasising the active role nature plays in influencing human affairs and vice versa.

The Plague of Athens was an epidemic that devastated the city-state of Athens in ancient Greece during the second year of the Peloponnesian War when an Athenian victory still seemed within reach. The plague killed an estimated 75,000 to 100,000 people, around 25% of the population, and is believed to have entered Athens through Piraeus, the city's port and sole source of food and supplies. Thucydides, an Athenian survivor, wrote that much of the eastern Mediterranean also saw an outbreak of the disease, albeit with less impact.

Ecological imperialism is an explanatory concept, introduced by Alfred Crosby, that points out the contribution of European biological species such as animals, plants and pathogens in the success of European colonists. Crosby wrote Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900-1900 in 1986. He used the term "Neo-Europes" to describe the places colonized and conquered by Europeans.

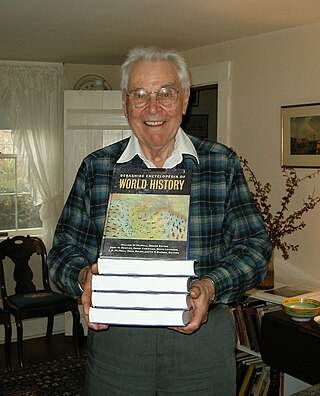

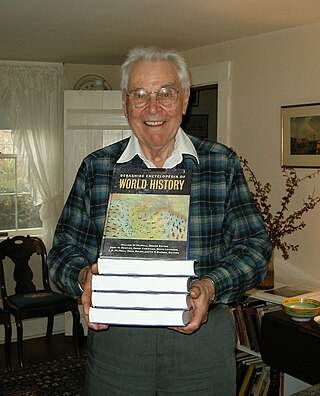

William Hardy McNeill was an American historian and author, noted for his argument that contact and exchange among civilizations is what drives human history forward, first postulated in The Rise of the West (1963). He was the Robert A. Millikan Distinguished Service Professor Emeritus of History at the University of Chicago, where he taught from 1947 until his retirement in 1987.

Globalization, the flow of information, goods, capital, and people across political and geographic boundaries, allows infectious diseases to rapidly spread around the world, while also allowing the alleviation of factors such as hunger and poverty, which are key determinants of global health. The spread of diseases across wide geographic scales has increased through history. Early diseases that spread from Asia to Europe were bubonic plague, influenza of various types, and similar infectious diseases.

In epidemiology, a disease vector is any living agent that carries and transmits an infectious pathogen such as a parasite or microbe, to another living organism. Agents regarded as vectors are mostly blood-sucking insects such as mosquitoes. The first major discovery of a disease vector came from Ronald Ross in 1897, who discovered the malaria pathogen when he dissected the stomach tissue of a mosquito.

The 1837 Great Plains smallpox epidemic spanned 1836 through 1840 but reached its height after the spring of 1837, when an American Fur Company steamboat, the SS St. Peter, carried infected people and supplies up the Missouri River in the Midwestern United States. The disease spread rapidly to indigenous populations with no natural immunity, causing widespread illness and death across the Great Plains, especially in the Upper Missouri River watershed. More than 17,000 Indigenous people died along the Missouri River alone, with some bands becoming nearly extinct.

The history of smallpox extends into pre-history. Genetic evidence suggests that the smallpox virus emerged 3,000 to 4,000 years ago. Prior to that, similar ancestral viruses circulated, but possibly only in other mammals, and possibly with different symptoms. Only a few written reports dating from about 500 AD to 1000 AD are considered reliable historical descriptions of smallpox, so understanding of the disease prior to that has relied on genetics and archaeology. However, during the 2nd millennium AD, especially starting in the 16th century, reliable written reports become more common. The earliest physical evidence of smallpox is found in the Egyptian mummies of people who died some 3,000 years ago. Smallpox has had a major impact on world history, not least because indigenous populations of regions where smallpox was non-native, such as the Americas and Australia, were rapidly and greatly reduced by smallpox during periods of initial foreign contact, which helped pave the way for conquest and colonization. During the 18th century the disease killed an estimated 400,000 Europeans each year, including five reigning monarchs, and was responsible for a third of all blindness. Between 20 and 60% of all those infected—and over 80% of infected children—died from the disease.

Although a variety of infectious diseases existed in the Americas in pre-Columbian times, the limited size of the populations, smaller number of domesticated animals with zoonotic diseases, and limited interactions between those populations hampered the transmission of communicable diseases. One notable infectious disease that may be of American origin is syphilis. Aside from that, most of the major infectious diseases known today originated in the Old World. The American era of limited infectious disease ended with the arrival of Europeans in the Americas and the Columbian exchange of microorganisms, including those that cause human diseases. Eurasian infections and epidemics had major effects on Native American life in the colonial period and nineteenth century, especially.

The social history of viruses describes the influence of viruses and viral infections on human history. Epidemics caused by viruses began when human behaviour changed during the Neolithic period, around 12,000 years ago, when humans developed more densely populated agricultural communities. This allowed viruses to spread rapidly and subsequently to become endemic. Viruses of plants and livestock also increased, and as humans became dependent on agriculture and farming, diseases such as potyviruses of potatoes and rinderpest of cattle had devastating consequences.

In epidemiology, a virgin soil epidemic is an epidemic in which populations that previously were in isolation from a pathogen are immunologically unprepared upon contact with the novel pathogen. Virgin soil epidemics have occurred with European colonization, particularly when European explorers and colonists brought diseases to lands they conquered in the Americas, Australia and Pacific Islands.

The Massachusetts smallpox epidemic or colonial epidemic was a smallpox outbreak that hit Massachusetts in 1633. Smallpox outbreaks were not confined to 1633 however, and occurred nearly every ten years. Smallpox was caused by two different types of variola viruses: variola major and variola minor. The disease was hypothesized to be transmitted due to an increase in the immigration of European settlers to the region who brought Old World smallpox aboard their ships.

Diseases and epidemics of the 19th century included long-standing epidemic threats such as smallpox, typhus, yellow fever, and scarlet fever. In addition, cholera emerged as an epidemic threat and spread worldwide in six pandemics in the nineteenth century.