Synopsis

We never learn her name, but the protagonist and principle narrator "Miss M." is playfully referred to as "Midgetina" by her faithless friend, Fanny. Hers is the story of a person who, though at home in nature and literature, is physically, spiritually, and intellectually out of place in the world. Her exact size is never made clear and seems to shift throughout the story. At times she is described as being of Thumbellina-like smallness. She recounts that she remembers as a child her father lifting her up in the palm of his hand to see herself in a small mirror. At the age of five or six, while sitting on a pomade jar watching her father shaving, she remembers being frightened when a jackdaw, attracted by her colourful red clothing, starts pecking at the window pane to get at her. She says she jumped up in alarm and ran away, tripping over a hairbrush, and falling sprawling beside a watch on his dressing table. She reads books that are taller than she is; and even at age twenty is carried on a tray and walks across the dining table. Yet she becomes a skilled horsewoman—riding sidesaddle on a pony—and at one point, we are told, can pass for a ten-year-old child.

Notwithstanding her stature Miss M.'s intellect is large and her perceptions preternaturally sharp. "Of a serious turn of mind", she studies astronomy; loves shells, fossils, flints, butterflies, taxidermy animals, and even investigates the phenomenon of death in the form of a maggot-eaten mole she finds rotting in her family's garden. She reads Elizabethan poetry, seventeenth century prose, and nineteenth century novels. Her family dotes on her, especially her grandfather, who is French, and who delights sending her miniature books and finely crafted custom furniture he has made for her. But her mother dies in a fall, possibly from fainting when Miss M. jokingly pretends to be dead, and her father, crushed by grief, soon follows, leaving his affairs in disarray. The house and furniture are sold to pay his debts. Miss M. at age 20 is left only with a small annual income from an unknown benefactor that in the course of the book, vanishes in a stock market downturn.

Most of the book's narrative covers the events of the twelve-month period between Miss M.'s twentieth and twenty-first years as she attempts to make her way in the world alone after the death of her parents. She lodges in the house of a dour but kindly, somewhat Dickensian, landlady, Mrs. Bowater, whose absent husband "follows the sea." Mrs. Bowater has a daughter Miss M.'s age, who teaches English at a provincial boys' school. "Beautiful, outspoken, and wonderfully alive", [2] Fanny Bowater is perhaps the book's most memorable and fully realized character. She comes home for the school holidays with a present for Miss M. of a red. hand-sewn jacket; and Miss M., in her turn, is smitten. The two go out together at night to study astronomy, though when they return home Fanny confides that the stars have never attracted her: "'Angels' tintacks' as they say in the Sunday schools. Fanny Bowater was looking for the moon." Consumed with ambition to escape her poverty and narrow surroundings, Fanny is "desperately capricious and of a cat-like cruelty." "A pitiless heartbreaker", critic Michael Dirda calls her, she "toys with Miss M., whose passions are awakened to such a pitch that today's readers may be astonished at the avowals not of girlish friendship but of passionate longing. But what can you expect from two young women who read Wuthering Heights together?" [3] Fanny has been stringing along the weak and unstable local curate, Mr. Crimble. He confides in Miss M., but she is herself ensnared by Fanny and is unable to help him. Miss M. advises Fanny to "cast the stone" and make a clean break with Mr. Crimble. She later learns Mr. Crimble has cut his throat with a knife. Fanny also repeatedly borrows money from Miss M.'s savings—it is implied at one point that she needs it for an abortion—finally draining them. Miss M., meanwhile, is courted by a brooding young man, whom she calls Mr. Anon, a name intended to be symbolic. Pale, dark-haired, and angular, Mr. Anon is a dwarf only four inches taller than herself. He lives in a cottage on the edge of the park of an abandoned mansion and has observed Miss M.s nocturnal star-gazing expeditions. Fanny calls Mr. Anon misshapen and ugly, but Miss M. states that the only thing grotesque about him are his oversized clothes—though in talking to Fanny she refers to him as a hunchback. Fanny's mother Mrs. Bowater, for her part, likes Mr. Anon. She speculates he may be the son of a lord, "Stranger things have happened", but fears he is unwell and may be tubercular. Miss M., however, is unable to return Mr. Anon's love. She rejects him and tells him she resents his watching over her.

Miss M. is taken up by the worldly and jaded Mrs. Monnerie, "the youngest daughter of Lord B.", whose blood is said to be "as blue as Caddis Bay on a cloudless morning." Mrs. Monnerie is a stout, mushroom-shaped woman of middle age who collects unusual objects and people. Highly intelligent, she is attracted as much by Miss M.'s wide reading and knowledge of poetry as by her unusual appearance, and she sets her up in her London house as a curiosity, a "pocket Venus" to be displayed at social gatherings. Mrs. Monnerie is likewise intrigued by Fanny Bowater's combination of beauty and cynicism and invites her into the household to be her personal companion. Unaware that everyone has read about it in the newspapers, Fanny makes Miss M. swear never to mention the affair of Mr. Crimble's suicide. She sets about to ensnare Miss Monnerie's empty-headed nephew Percy Maudlen and also flirts with the handsome fiancé of Miss Monnerie's niece Susan, a kind and considerate young woman, the polar opposite of Fanny, causing the breakup of that couple. Disgusted with her life in captivity as a living bibelot and wounded by Fanny's coldness, Miss M. becomes increasingly bad tempered. Her sourness offends her patroness and she is banished to Monk's House, Mrs. Monnerie's country residence. There Fanny visits her and accuses her of having betrayed her by breaking her promise not to gossip about the past. She tells Miss M. she hates her:

I can't endure the sight or sound or creep of you any longer. . . . Why? Because of your unspeakable masquerade. You play the pygmy, carried about, cosseted, smirked at . . . . But where have you come from? What are you in your past—in your mind? I ask you that: a thing more everywhere, more thief-like, more detestable than a conscience. Look at me, as we sit here now. I am the monstrosity. You see it, you think it, you hate even to touch me. From first moment to last you have secretly despised me—me! . . . these last nights I have lain awake and thought of it all. It came on me as if my life had been nothing but a filthy, aimless nightmare; and chiefly because of you. I've worked, I've thought, I've contrived, and forced my way. . . I refuse to be watched and taunted and goaded and defamed. [4]

Miss M. in turn (erroneously) believes Fanny has made fun of her relationship with Mr. Anon behind her back.

Miss M. resolves to achieve financial and spiritual independence by becoming a fortune teller and horseback rider in a circus and discovers that she likes and is good at performing. She also realizes that she now reciprocates Mr. Anon's love and friendship, and she promises to come away with him and set up housekeeping nearby, implying that they will marry at some future time. Mr. Anon insists that they leave immediately and that she stop displaying herself in public. Miss M. angrily refuses. She has performed for two of the three nights she promised the circus manager—in exchange for a large sum—though she is ashamed to mention the money to Mr. Anon, presenting it as a matter of not breaking her contract. They arrange for Mr. Anon to take Miss M.'s place in the ring for the last evening. Dressed in woman's clothes, he rides out, sidesaddle—to the jeers and mockery of the crowd. There is an accident and he is thrown from the horse and seriously injured, though he remounts and finishes his ride. As he and Miss M. leave together in his pony cart, he dies, just as Miss M. realises the depth of his love for her and the extent of her own recklessness and ingratitude. Tormented by guilt she wanders alone in the woods, fighting the impulse to kill herself. She is deterred, finally, by her conviction that only through leaving the world in a peaceful frame of mind will she be likely to meet her lover after death. In the meantime, her financial trustee, Sir Walter Pollacke, a banker, has been able to restore her fortune, enabling her repurchase her family home. The frame story of the novel, an introduction narrated by Sir Walter, recounts that Miss M. went on to live comfortably for many years in the house of her birth, seeing few people, with Mrs. Bowater as her housekeeper and himself as an occasional visitor. Mrs. Bowater has told Sir Walter that one evening she heard mysterious voices coming from Miss M.s room and when she went to check found no one, only a note from Miss M. saying that she had been "called away", perhaps, the reader is left to conclude, to the spirit world to join her lover in another dimension.

Critical reception

Memoirs of a Midget was published to high praise in 1921 and in that year received the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for fiction. Rebecca West later included Memoirs of a Midget on a list of the "best imaginative productions of the last decade in England". [5] Though it has since fallen into semi-obscurity, it still has its devoted admirers. Michael Dirda, book columnist for The Washington Post , notes that the American critic Edward Wagenknecht regarded Memoirs of a Midget "as the greatest English novel of its time." Dirda, himself a fan, adds, "(I'm not sure I'd disagree with him, even if nobody seems to read the book anymore: those interested can consult the essay on Memoirs of a Midget in my book Classics for Pleasure.) Born in 1900, Wagenknecht lived until 2004, publishing a book on Willa Cather when he was 94. I’ve sometimes wondered if he ever changed his mind about De la Mare or Memoirs of a Midget. I hope he didn't." [6] Dirda reminds us that the 1920s in Britain were a time that writers experimented in fantasy and unusual perspectives:

Yet for all its strangeness of perspective, Memoirs of a Midget may be regarded as one of the best novels Henry James never wrote. Its narrative voice is often severe, formal, elliptical, and diffuse, so much so that the book might well have been called "What Miss M. Knew." A reader who fails to pay attention will overlook for a long while, that Mrs. Bowater is not Fanny's real mother; that Mr. Anon is a hunchback; that Fanny probably needs money for an abortion; that the Reverend Crimble is going insane; and that Miss M. thinks a bit too well of herself. It is also, as in so much James, a book containing a considerable amount of death, violence, madness, and grotesquerie. "The world", writes Miss M., "wields a sharp pin, and is pitiless to bubbles." [7]

Dirda concludes that although Memoirs of a Midget is perhaps "too odd" to merit Wagenknecht's "blanket encomium", "in its sheer originality and uniqueness it is unforgettable. It lingers in the memory like a ghostly visitation or dream." [8]

In her preface to a 1982 edition of the book Angela Carter calls Memoirs of a Midget "a minor but authentic masterpiece, a novel that clearly sets out with the intention of being unique and, in fact, is so; lucid, enigmatic, and violent with the terrible violence that leaves behind no physical trace." [9]

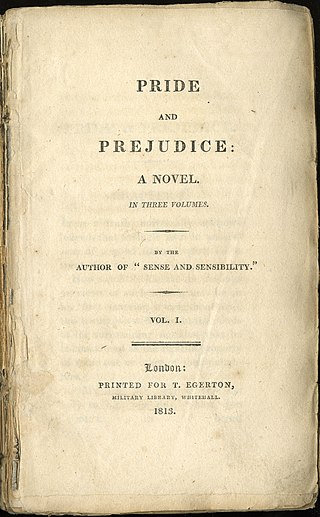

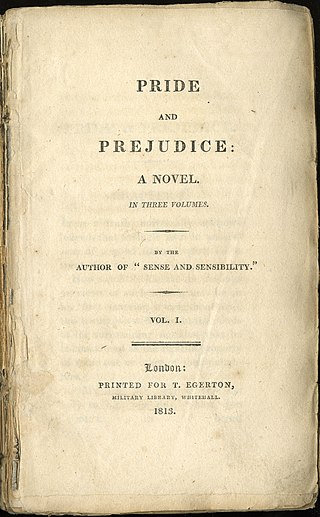

Pride and Prejudice is the second novel by English author Jane Austen, published in 1813. A novel of manners, it follows the character development of Elizabeth Bennet, the protagonist of the book, who learns about the repercussions of hasty judgments and comes to appreciate the difference between superficial goodness and actual goodness.

Sense and Sensibility is the first novel by the English author Jane Austen, published in 1811. It was published anonymously; By A Lady appears on the title page where the author's name might have been. It tells the story of the Dashwood sisters, Elinor and Marianne as they come of age. They have an older half-brother, John, and a younger sister, Margaret.

Jane Eyre is a novel by the English writer Charlotte Brontë. It was published under her pen name "Currer Bell" on 19 October 1847 by Smith, Elder & Co. of London. The first American edition was published the following year by Harper & Brothers of New York. Jane Eyre is a bildungsroman that follows the experiences of its eponymous heroine, including her growth to adulthood and her love for Mr Rochester, the brooding master of Thornfield Hall.

Emma is a novel written by English author Jane Austen. It is set in the fictional country village of Highbury and the surrounding estates of Hartfield, Randalls and Donwell Abbey, and involves the relationships among people from a small number of families. The novel was first published in December 1815, although the title page is dated 1816. As in her other novels, Austen explores the concerns and difficulties of genteel women living in Georgian–Regency England. Emma is a comedy of manners.

Little Dorrit is a novel by Charles Dickens, originally published in serial form between 1855 and 1857. The story features Amy Dorrit, youngest child of her family, born and raised in the Marshalsea prison for debtors in London. Arthur Clennam encounters her after returning home from a 20-year absence, ready to begin his life anew.

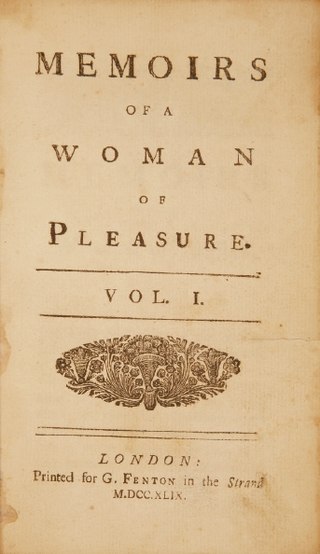

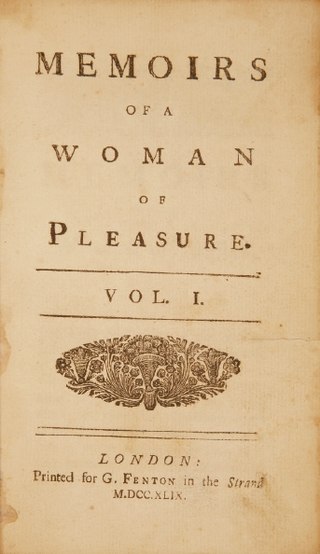

Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure—popularly known as Fanny Hill—is an erotic novel by the English novelist John Cleland first published in London in 1748. Written while the author was in debtors' prison in London, it is considered "the first original English prose pornography, and the first pornography to use the form of the novel". It is one of the most prosecuted and banned books in history.

John Cleland was an English novelist best known for his fictional Fanny Hill: or, the Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, whose eroticism led to his arrest. James Boswell called him "a sly, old malcontent".

Walter John de la Mare was an English poet, short story writer and novelist. He is probably best remembered for his works for children, for his poem "The Listeners", and for his psychological horror short fiction, including "Seaton's Aunt" and "All Hallows". In 1921, his novel Memoirs of a Midget won the James Tait Black Memorial Prize for fiction, and his post-war Collected Stories for Children won the 1947 Carnegie Medal for British children's books.

Persuasion is the last novel completed by the English author Jane Austen. It was published on 20 December 1817, along with Northanger Abbey, six months after her death, although the title page is dated 1818.

Nicholas Nickleby, or The Life and Adventures of Nicholas Nickleby, is the third novel by Charles Dickens, originally published as a serial from 1838 to 1839. The character of Nickleby is a young man who must support his mother and sister after his father dies.

Evelina, or the History of a Young Lady's Entrance into the World is a novel written by English author Fanny Burney and first published in 1778. Although published anonymously, its authorship was revealed by the poet George Huddesford in what Burney called a "vile poem".

Dombey and Son is a novel by English author Charles Dickens. It follows the fortunes of a shipping firm owner, who is frustrated at the lack of a son to follow him in his footsteps; he initially rejects his daughter's love before eventually becoming reconciled with her before his death.

The Awkward Age is a novel by Henry James, first published as a serial in Harper's Weekly in 1898–1899 and then as a book later in 1899. Originally conceived as a brief, light story about the complications created in her family's social set by a young girl coming of age, the novel expanded into a general treatment of decadence and corruption in English fin de siècle life.

Jessamy (1967) is a children's book by Barbara Sleigh, author of the Carbonel series. It sheds light on English life and childhood in the First World War, through a good-natured pre-adolescent female character, presented in detail, and a realistically written time-slip narrative.

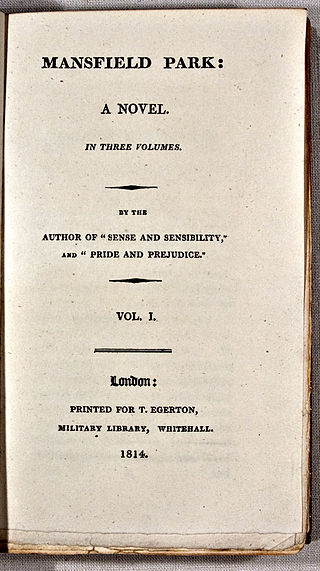

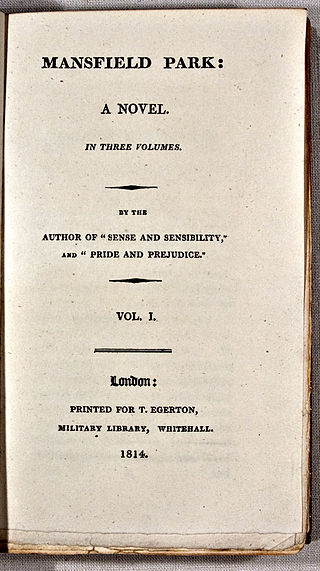

Mansfield Park is the third published novel by the English author Jane Austen, first published in 1814 by Thomas Egerton. A second edition was published in 1816 by John Murray, still within Austen's lifetime. The novel did not receive any public reviews until 1821.

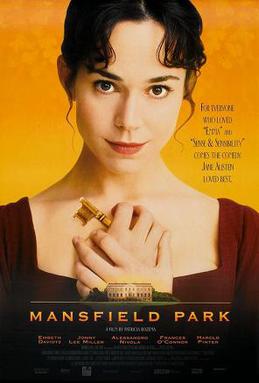

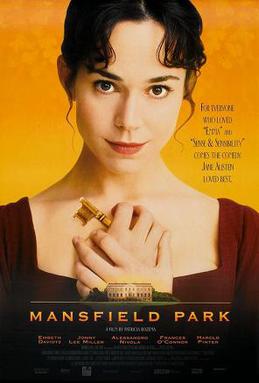

Mansfield Park is a 1999 British romantic comedy-drama film based on Jane Austen's 1814 novel of the same name, written and directed by Patricia Rozema. The film departs from the original novel in several respects. For example, the life of Jane Austen is incorporated into the film, as are the issues of slavery and West Indian plantations. The majority of the film was filmed on location at Kirby Hall in Northamptonshire.

Fanny Hill is a BBC adaptation of John Cleland's controversial 1748 novel Fanny Hill, written by Andrew Davies and directed by James Hawes. This is the first television adaptation of the novel. Fanny Hill was broadcast in October 2007 on BBC Four in two episodes. Fanny Hill tells the story of a young country girl who is lured into prostitution in 18th-century London.

Frances "Fanny" Price is the heroine in Jane Austen's 1814 novel, Mansfield Park. The novel begins when Fanny's overburdened, impoverished family—where she is both the second-born and the eldest daughter out of 10 children—sends her at the age of ten to live in the household of her wealthy uncle, Sir Thomas Bertram, and his family at Mansfield Park. The novel follows her growth and development, concluding in early adulthood.

Sense and Sensibility and Sea Monsters (2009) is a parody novel by Ben H. Winters, with Jane Austen credited as co-author. It is a mashup story containing elements from Jane Austen's 1811 novel Sense and Sensibility and common tropes from sea monster stories. It is the thematic sequel to another 2009 novel from the same publisher called Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. It was first published by Quirk Books on September 15, 2009.