Health informatics is the study and implementation of computer structures and algorithms to improve communication, understanding, and management of medical information. It can be viewed as a branch of engineering and applied science.

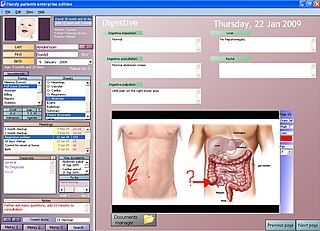

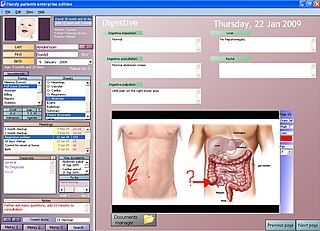

An electronic health record (EHR) is the systematized collection of patient and population electronically stored health information in a digital format. These records can be shared across different health care settings. Records are shared through network-connected, enterprise-wide information systems or other information networks and exchanges. EHRs may include a range of data, including demographics, medical history, medication and allergies, immunization status, laboratory test results, radiology images, vital signs, personal statistics like age and weight, and billing information.

Telehealth is the distribution of health-related services and information via electronic information and telecommunication technologies. It allows long-distance patient and clinician contact, care, advice, reminders, education, intervention, monitoring, and remote admissions. Telemedicine is sometimes used as a synonym, or is used in a more limited sense to describe remote clinical services, such as diagnosis and monitoring. When rural settings, lack of transport, a lack of mobility, conditions due to outbreaks, epidemics or pandemics, decreased funding, or a lack of staff restrict access to care, telehealth may bridge the gap as well as provide distance-learning; meetings, supervision, and presentations between practitioners; online information and health data management and healthcare system integration. Telehealth could include two clinicians discussing a case over video conference; a robotic surgery occurring through remote access; physical therapy done via digital monitoring instruments, live feed and application combinations; tests being forwarded between facilities for interpretation by a higher specialist; home monitoring through continuous sending of patient health data; client to practitioner online conference; or even videophone interpretation during a consult.

eHealth describes healthcare services which are supported by digital processes, communication or technology such as electronic prescribing, Telehealth, or Electronic Health Records (EHRs). The use of electronic processes in healthcare dated back to at least the 1990s. Usage of the term varies as it covers not just "Internet medicine" as it was conceived during that time, but also "virtually everything related to computers and medicine". A study in 2005 found 51 unique definitions. Some argue that it is interchangeable with health informatics with a broad definition covering electronic/digital processes in health while others use it in the narrower sense of healthcare practice using the Internet. It can also include health applications and links on mobile phones, referred to as mHealth or m-Health. Key components of eHealth include electronic health records (EHRs), telemedicine, health information exchange, mobile health applications, wearable devices, and online health information. These technologies enable healthcare providers, patients, and other stakeholders to access, manage, and exchange health information more effectively, leading to improved communication, decision-making, and overall healthcare outcomes.

Telenursing refers to the use of information technology in the provision of nursing services whenever physical distance exists between patient and nurse, or between any number of nurses. As a field, it is part of telemedicine, and has many points of contacts with other medical and non-medical applications, such as telediagnosis, teleconsultation, and telemonitoring. The field, however, is still being developed as the information on telenursing isn't comprehensive enough.

A personal health record (PHR) is a health record where health data and other information related to the care of a patient is maintained by the patient. This stands in contrast to the more widely used electronic medical record, which is operated by institutions and contains data entered by clinicians to support insurance claims. The intention of a PHR is to provide a complete and accurate summary of an individual's medical history which is accessible online. The health data on a PHR might include patient-reported outcome data, lab results, and data from devices such as wireless electronic weighing scales or from a smartphone.

Telepsychiatry or telemental health refers to the use of telecommunications technology to deliver psychiatric care remotely for people with mental health conditions. It is a branch of telemedicine.

Home automation for the elderly and disabled focuses on making it possible for older adults and people with disabilities to remain at home, safe and comfortable. Home automation is becoming a viable option for older adults and people with disabilities who would prefer to stay in the comfort of their homes rather than move to a healthcare facility. This field uses much of the same technology and equipment as home automation for security, entertainment, and energy conservation but tailors it towards old people and people with disabilities.

Protected health information (PHI) under U.S. law is any information about health status, provision of health care, or payment for health care that is created or collected by a Covered Entity, and can be linked to a specific individual. This is interpreted rather broadly and includes any part of a patient's medical record or payment history.

mHealth is an abbreviation for mobile health, a term used for the practice of medicine and public health supported by mobile devices. The term is most commonly used in reference to using mobile communication devices, such as mobile phones, tablet computers and personal digital assistants (PDAs), and wearable devices such as smart watches, for health services, information, and data collection. The mHealth field has emerged as a sub-segment of eHealth, the use of information and communication technology (ICT), such as computers, mobile phones, communications satellite, patient monitors, etc., for health services and information. mHealth applications include the use of mobile devices in collecting community and clinical health data, delivery/sharing of healthcare information for practitioners, researchers and patients, real-time monitoring of patient vital signs, the direct provision of care as well as training and collaboration of health workers.

Services for mental health disorders provide treatment, support, or advocacy to people who have psychiatric illnesses. These may include medical, behavioral, social, and legal services.

A doctor's visit, also known as a physician office visit or a consultation, or a ward round in an inpatient care context, is a meeting between a patient with a physician to get health advice or treatment plan for a symptom or condition, most often at a professional health facility such as a doctor's office, clinic or hospital. According to a survey in the United States, a physician typically sees between 50 and 100 patients per week, but it may vary with medical specialty, but differs only little by community size such as metropolitan versus rural areas.

The use of electronic and communication technologies as a therapeutic aid to healthcare practices is commonly referred to as telemedicine or eHealth. The use of such technologies as a supplement to mainstream therapies for mental disorders is an emerging mental health treatment field which, it is argued, could improve the accessibility, effectiveness and affordability of mental health care. Mental health technologies used by professionals as an adjunct to mainstream clinical practices include email, SMS, virtual reality, computer programs, blogs, social networks, the telephone, video conferencing, computer games, instant messaging and podcasts.

Remote patient monitoring (RPM) is a technology to enable monitoring of patients outside of conventional clinical settings, such as in the home or in a remote area, which may increase access to care and decrease healthcare delivery costs. RPM involves the constant remote care of patients by their physicians, often to track physical symptoms, chronic conditions, or post-hospitalization rehab.

Digital health is a discipline that includes digital care programs, technologies with health, healthcare, living, and society to enhance the efficiency of healthcare delivery and to make medicine more personalized and precise. It uses information and communication technologies to facilitate understanding of health problems and challenges faced by people receiving medical treatment and social prescribing in more personalised and precise ways. The definitions of digital health and its remits overlap in many ways with those of health and medical informatics.

Health care analytics is the health care analysis activities that can be undertaken as a result of data collected from four areas within healthcare; claims and cost data, pharmaceutical and research and development (R&D) data, clinical data, and patient behavior and sentiment data (patient behaviors and preferences,. Health care analytics is a growing industry in the United States, expected to grow to more than $31 billion by 2022. The industry focuses on the areas of clinical analysis, financial analysis, supply chain analysis, as well as marketing, fraud and HR analysis.

Digital therapeutics, a subset of digital health, are evidence-based therapeutic interventions driven by high quality software programs to prevent, manage, or treat a medical disorder or disease. Digital therapeutic companies should publish trial results inclusive of clinically meaningful outcomes in peer-reviewed journals. The treatment relies on behavioral and lifestyle changes usually spurred by a collection of digital impetuses. Because of the digital nature of the methodology, data can be collected and analyzed as both a progress report and a preventative measure. Treatments are being developed for the prevention and management of a wide variety of diseases and conditions, including type 1 & type II diabetes, congestive heart failure, obesity, Alzheimer's disease, dementia, asthma, substance abuse, ADHD, hypertension, anxiety, depression, and several others. Digital therapeutics often employ strategies rooted in cognitive behavioral therapy.

Health data is any data "related to health conditions, reproductive outcomes, causes of death, and quality of life" for an individual or population. Health data includes clinical metrics along with environmental, socioeconomic, and behavioral information pertinent to health and wellness. A plurality of health data are collected and used when individuals interact with health care systems. This data, collected by health care providers, typically includes a record of services received, conditions of those services, and clinical outcomes or information concerning those services. Historically, most health data has been sourced from this framework. The advent of eHealth and advances in health information technology, however, have expanded the collection and use of health data—but have also engendered new security, privacy, and ethical concerns. The increasing collection and use of health data by patients is a major component of digital health.

Internet-based treatments for trauma survivors is a growing class of online treatments that allow for an individual who has experienced trauma to seek and receive treatment without needing to attend psychotherapy in person. The progressive movement to online resources and the need for more accessible mental health services has given rise to the creation of online-based interventions aimed to help those who have experienced traumatic events. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) has shown to be particularly effective in the treatment of trauma-related disorders and adapting CBT to an online format has been shown to be as effective as in-person CBT in the treatment of trauma. Due to its positive outcomes, CBT-based internet treatment options for trauma survivors has been an expanding field in both research and clinical settings.

Before the COVID-19 pandemic, telehealth adoption was gradually increasing. Some patients preferred in-person consultations and expressed concerns about privacy during video calls. However, with the outbreak of COVID-19 in early 2020, healthcare professionals reduced in-person visits to minimize exposure. As a result, telehealth usage surged dramatically, experiencing a 5,000% increase from February to March 2020. Telehealth has since remained widely utilized in healthcare services.