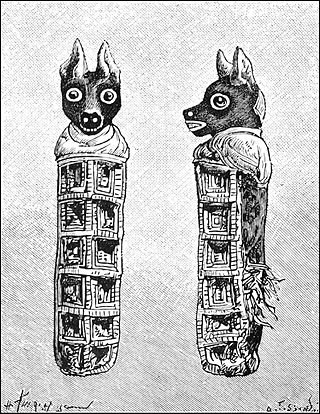

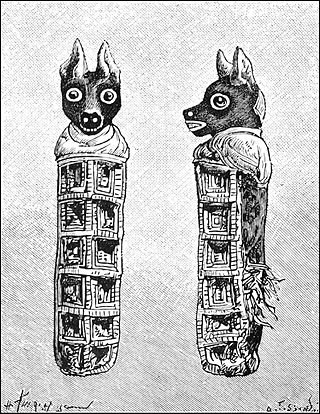

Zooarchaeology or archaeozoology merges the disciplines of zoology and archaeology, focusing on the analysis of animal remains within archaeological sites. This field, managed by specialists known as zooarchaeologists or faunal analysts, examines remnants such as bones, shells, hair, chitin, scales, hides, and proteins, such as DNA, to derive insights into historical human-animal interactions and environmental conditions. While bones and shells tend to be relatively more preserved in archaeological contexts, the survival of faunal remains is generally infrequent. The degradation or fragmentation of faunal remains presents challenges in the accurate analysis and interpretation of data.

Processual archaeology is a form of archaeological theory. It had its beginnings in 1958 with the work of Gordon Willey and Philip Phillips, Method and Theory in American Archaeology, in which the pair stated that "American archaeology is anthropology, or it is nothing", a rephrasing of Frederic William Maitland's comment: "My own belief is that by and by, anthropology will have the choice between being history, and being nothing." The idea implied that the goals of archaeology were the goals of anthropology, which were to answer questions about humans and human culture. This was meant to be a critique of the former period in archaeology, the cultural-history phase in which archaeologists thought that information artifacts contained about past culture would be lost once the items became included in the archaeological record. Willey and Phillips believed all that could be done was to catalogue, describe, and create timelines based on the artifacts.

Lewis Roberts Binford was an American archaeologist known for his influential work in archaeological theory, ethnoarchaeology and the Paleolithic period. He is widely considered among the most influential archaeologists of the later 20th century, and is credited with fundamentally changing the field with the introduction of processual archaeology in the 1960s. Binford's influence was controversial, however, and most theoretical work in archaeology in the late 1980s and 1990s was explicitly construed as either a reaction to or in support of the processual paradigm. Recent appraisals have judged that his approach owed more to prior work in the 1940s and 50s than suggested by Binford's strong criticism of his predecessors.

Ethnoarchaeology is the ethnographic study of peoples for archaeological reasons, usually through the study of the material remains of a society. Ethnoarchaeology aids archaeologists in reconstructing ancient lifeways by studying the material and non-material traditions of modern societies. Ethnoarchaeology also aids in the understanding of the way an object was made and the purpose of what it is being used for. Archaeologists can then infer that ancient societies used the same techniques as their modern counterparts given a similar set of environmental circumstances.

Environmental archaeology is a sub-field of archaeology which emerged in 1970s and is the science of reconstructing the relationships between past societies and the environments they lived in. The field represents an archaeological-palaeoecological approach to studying the palaeoenvironment through the methods of human palaeoecology and other geosciences. Reconstructing past environments and past peoples' relationships and interactions with the landscapes they inhabited provide archaeologists with insights into the origins and evolution of anthropogenic environments and human systems. This includes subjects such as including prehistoric lifestyle adaptations to change and economic practices.

Cognitive archaeology is a theoretical perspective in archaeology that focuses on the ancient mind. It is divided into two main groups: evolutionary cognitive archaeology (ECA), which seeks to understand human cognitive evolution from the material record, and ideational cognitive archaeology (ICA), which focuses on the symbolic structures discernable in or inferable from past material culture.

Archaeological theory refers to the various intellectual frameworks through which archaeologists interpret archaeological data. Archaeological theory functions as the application of philosophy of science to archaeology, and is occasionally referred to as philosophy of archaeology. There is no one singular theory of archaeology, but many, with different archaeologists believing that information should be interpreted in different ways. Throughout the history of the discipline, various trends of support for certain archaeological theories have emerged, peaked, and in some cases died out. Different archaeological theories differ on what the goals of the discipline are and how they can be achieved.

Alfred Vincent Kidder was an American archaeologist considered the foremost of the southwestern United States and Mesoamerica during the first half of the 20th century. He saw a disciplined system of archaeological techniques as a means to extend the principles of anthropology into the prehistoric past and so was the originator of the first comprehensive, systematic approach to North American archaeology.

George L. Cowgill was an American anthropologist and archaeologist. He was a professor of anthropology at Arizona State University from 1990-2005, and research professor emeritus from 2005 until his death. He received his PhD from Harvard in 1963 with a dissertation on The Post-Classic Period in the Southern Maya Lowlands. Most of his career was devoted to research at the ancient Mexican city of Teotihuacán. He taught at Brandeis University between 1960 and 1990. Cowgill made important contributions in a number of areas, including the archaeology of Mesoamerica, the comparative study of early states and cities, and quantitative methods in archaeology.

The Sobaipuri were one of many indigenous groups occupying Sonora and what is now Arizona at the time Europeans first entered the American Southwest. They were a Piman or O'odham group who occupied southern Arizona and northern Sonora in the 15th–19th centuries. They were a subgroup of the O'odham or Pima, surviving members of which include the residents of San Xavier del Bac which is now part of the Tohono O'odham Nation and the Akimel O'odham.

Archaeology or archeology is the study of human activity through the recovery and analysis of material culture. The archaeological record consists of artifacts, architecture, biofacts or ecofacts, sites, and cultural landscapes. Archaeology can be considered both a social science and a branch of the humanities. It is usually considered an independent academic discipline, but may also be classified as part of anthropology, history or geography. The discipline involves surveying, excavation, and eventually analysis of data collected, to learn more about the past. In broad scope, archaeology relies on cross-disciplinary research.

The archaeology of religion and ritual is a growing field of study within archaeology that applies ideas from religious studies, theory and methods, anthropological theory, and archaeological and historical methods and theories to the study of religion and ritual in past human societies from a material perspective.

Albert Clanton Spaulding was an American anthropologist and processual archaeologist who encouraged the application of quantitative statistics in archaeological research and the legitimacy of anthropology as a science. His push for thorough statistical analysis in the field triggered a series of academic debates with archaeologist James Ford in which the nature of archaeological typologies was meticulously investigated—a dynamic discourse now known as the Ford-Spaulding Debate. He was also instrumental in increasing funding for archaeology through the National Science Foundation.

Sally Binford was an archaeologist and feminist. A prehistorian, she contributed alongside her husband to the formation of processual archaeology.

There are two main approaches currently used to analyze archaeological remains from an evolutionary perspective: evolutionary archaeology and behavioral ecology. The former assumes that cultural change observed in the archaeological record can be best explained by the direct action of natural selection and other Darwinian processes on heritable variation in artifacts and behavior. The latter assumes that cultural and behavioral change results from phenotypic adaptations to varying social and ecological environments.

James M. Skibo was an American archaeologist who was the State Archaeologist of Wisconsin from 2021 to 2023. His archaeological research focused on the production and use of ceramics as well as the theory of archaeology and ethnoarchaeology. He was mainly concerned with the Great Lakes, the Southwest United States, and the Philippines.

Behavioural archaeology is an archaeological theory that expands upon the nature and aims of archaeology in regards to human behaviour and material culture. The theory was first published in 1975 by American archaeologist Michael B. Schiffer and his colleagues J. Jefferson Reid, and William L. Rathje. The theory proposes four strategies that answer questions about past, and present cultural behaviour. It is also a means for archaeologists to observe human behaviour and the archaeological consequences that follow.

Carol Kramer was an American archaeologist known for conducting ethnoarchaeology research in the Middle East and South Asia. Kramer also advocated for women in anthropology and archaeology, receiving the Squeaky Wheel Award from the Committee on the Status of Women in Anthropology in 1999. Kramer co-wrote Ethnoarchaeology in Action (2001) with Nicolas David, the first comprehensive text on ethnoarchaeology, and received the Award for Excellence in Archaeological Analysis posthumously in 2003.

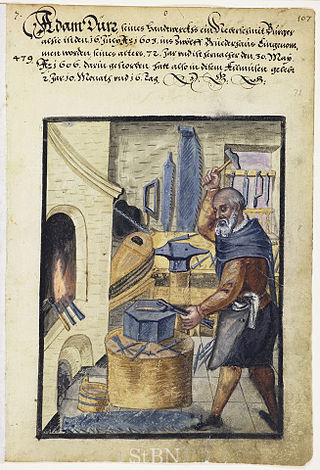

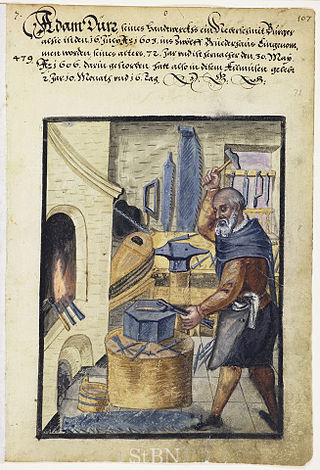

The anthropology of technology (AoT) is a unique, diverse, and growing field of study that bears much in common with kindred developments in the sociology and history of technology: first, a growing refusal to view the role of technology in human societies as the irreversible and predetermined consequence of a given technology's putative "inner logic"; and second, a focus on the social and cultural factors that shape a given technology's development and impact in a society. However, AoT defines technology far more broadly than the sociologists and historians of technology.

William A. Longacre II was an American archaeologist and one of the founders of the processual "New Archaeology" of the 1960s.