The visual system is the physiological basis of visual perception. The system detects, transduces and interprets information concerning light within the visible range to construct an image and build a mental model of the surrounding environment. The visual system is associated with the eye and functionally divided into the optical system and the neural system.

Amblyopia, also called lazy eye, is a disorder of sight in which the brain fails to fully process input from one eye and over time favors the other eye. It results in decreased vision in an eye that typically appears normal in other aspects. Amblyopia is the most common cause of decreased vision in a single eye among children and younger adults.

Sensory substitution is a change of the characteristics of one sensory modality into stimuli of another sensory modality.

Visual or vision impairment is the partial or total inability of visual perception. In the absence of treatment such as corrective eyewear, assistive devices, and medical treatment, visual impairment may cause the individual difficulties with normal daily tasks, including reading and walking. The terms low vision and blindness are often used for levels of impairment which are difficult or impossible to correct and significantly impact daily life. In addition to the various permanent conditions, fleeting temporary vision impairment, amaurosis fugax, may occur, and may indicate serious medical problems.

Cortical blindness is the total or partial loss of vision in a normal-appearing eye caused by damage to the brain's occipital cortex. Cortical blindness can be acquired or congenital, and may also be transient in certain instances. Acquired cortical blindness is most often caused by loss of blood flow to the occipital cortex from either unilateral or bilateral posterior cerebral artery blockage and by cardiac surgery. In most cases, the complete loss of vision is not permanent and the patient may recover some of their vision. Congenital cortical blindness is most often caused by perinatal ischemic stroke, encephalitis, and meningitis. Rarely, a patient with acquired cortical blindness may have little or no insight that they have lost vision, a phenomenon known as Anton–Babinski syndrome.

Paralympic cross-country skiing is an adaptation of cross-country skiing for athletes with disabilities. Paralympic cross-country skiing is one of two Nordic skiing disciplines in the Winter Paralympic Games; the other is biathlon. Competition is governed by the International Paralympic Committee (IPC).

Recovery from blindness is the phenomenon of a blind person gaining the ability to see, usually as a result of medical treatment. As a thought experiment, the phenomenon is usually referred to as Molyneux's problem. It is often stated that the first published human case was reported in 1728 by the surgeon William Cheselden. However, there is no evidence that Cheselden's patient, Daniel Dolins, actually recovered any vision. Patients who experience dramatic recovery from blindness experience significant to total visual agnosia – serious confusion with their visual perception.

The Paralympic sports comprise all the sports contested in the Summer and Winter Paralympic Games. As of 2020, the Summer Paralympics included 22 sports and 539 medal events, and the Winter Paralympics include 5 sports and disciplines and about 80 events. The number and kinds of events may change from one Paralympic Games to another.

The Winter Paralympic Games is an international multi-sport event where athletes with physical disabilities compete in snow and ice sports. The event includes athletes with mobility impairments, amputations, blindness, and cerebral palsy. The Winter Paralympic Games are held every four years directly following the Winter Olympic Games and hosted in the same city. The International Paralympic Committee (IPC) oversees the Games. Medals are awarded in each event: with gold for first place, silver for second, and bronze for third, following the tradition that the Olympic Games began in 1904.

The effects of sleep deprivation on cognitive performance are a broad range of impairments resulting from inadequate sleep, impacting attention, executive function and memory. An estimated 20% of adults or more have some form of sleep deprivation. It may come with insomnia or major depressive disorder, or indicate other mental disorders. The consequences can negatively affect the health, cognition, energy level and mood of a person and anyone around. It increases the risk of human error, especially with technology.

A sighted guide is a person who guides a person with blindness or vision impairment.

Cross modal plasticity is the adaptive reorganization of neurons to integrate the function of two or more sensory systems. Cross modal plasticity is a type of neuroplasticity and often occurs after sensory deprivation due to disease or brain damage. The reorganization of the neural network is greatest following long-term sensory deprivation, such as congenital blindness or pre-lingual deafness. In these instances, cross modal plasticity can strengthen other sensory systems to compensate for the lack of vision or hearing. This strengthening is due to new connections that are formed to brain cortices that no longer receive sensory input.

Form perception is the recognition of visual elements of objects, specifically those to do with shapes, patterns and previously identified important characteristics. An object is perceived by the retina as a two-dimensional image, but the image can vary for the same object in terms of the context with which it is viewed, the apparent size of the object, the angle from which it is viewed, how illuminated it is, as well as where it resides in the field of vision. Despite the fact that each instance of observing an object leads to a unique retinal response pattern, the visual processing in the brain is capable of recognizing these experiences as analogous, allowing invariant object recognition. Visual processing occurs in a hierarchy with the lowest levels recognizing lines and contours, and slightly higher levels performing tasks such as completing boundaries and recognizing contour combinations. The highest levels integrate the perceived information to recognize an entire object. Essentially object recognition is the ability to assign labels to objects in order to categorize and identify them, thus distinguishing one object from another. During visual processing information is not created, but rather reformatted in a way that draws out the most detailed information of the stimulus.

B1 is a medical-based Paralympic classification for blind sport. Athletes in this classification are totally or almost totally blind. It is used by a number of blind sports including blind tennis, para-alpine skiing, para-Nordic skiing, blind cricket, blind golf, five-a-side football, goalball and judo. Some other sports, including adaptive rowing, athletics and swimming, have equivalents to this class.

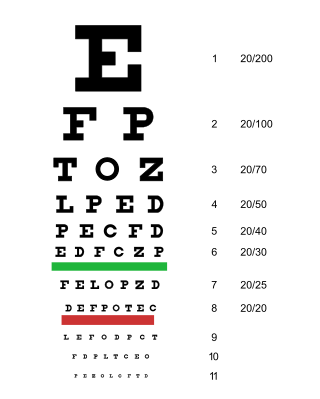

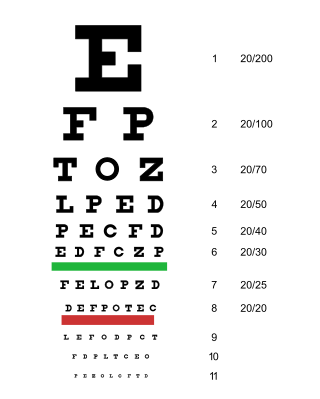

B2 is a medical based Paralympic classification for blind sport. Competitors in this classification have vision that falls between the B1 and B3 classes. The International Blind Sports Federation (IBSA) defines this classification as "visual acuity ranging from LogMAR 1.50 to 2.60 (inclusive) and/or visual field constricted to a diameter of less than 10 degrees." It is used by a number of blind sports including para-alpine skiing, para-Nordic skiing, blind cricket, blind golf, five-a-side football, goalball and judo. Some sports, including adaptive rowing, athletics and swimming, have equivalents to this class.

B3 is a medical based Paralympic classification for blind sport. Competitors in this classification have partial sight, with visual acuity from 2/60 to 6/60. It is used by a number of blind sports including para-alpine skiing, para-Nordic skiing, blind cricket, blind golf, five-a-side football, goalball and judo. Some other sports, including adaptive rowing, athletics and swimming, have equivalents to this class.

Para-alpine skiing classification is the classification system for para-alpine skiing designed to ensure fair competition between alpine skiers with different types of disabilities. The classifications are grouped into three general disability types: standing, blind and sitting. Classification governance is handled by International Paralympic Committee Alpine Skiing. Prior to that, several sport governing bodies dealt with classification including the International Sports Organization for the Disabled (ISOD), International Stoke Mandeville Games Federation (ISMWSF), International Blind Sports Federation (IBSA) and Cerebral Palsy International Sports and Recreation Association (CP-ISRA). Some classification systems are governed by bodies other than International Paralympic Committee Alpine Skiing, such as the Special Olympics. The sport is open to all competitors with a visual or physical disability. It is not open to people with intellectual disabilities.

Para-Nordic skiing classification is the classification system for para-Nordic skiing which includes the biathlon and cross-country events. The classifications for Para-Nordic skiing mirrors the classifications for Para-Alpine skiing with some exceptions. A functional mobility and medical classification is in use, with skiers being divided into three groups: standing skiers, sit skiers and visually impaired skiers. International classification is governed by International Paralympic Committee, Nordic Skiing (IPC-NS). Other classification is handled by national bodies. Before the IPC-NS took over classification, a number of organizations handled classification based on the type of disability.

Sight Scotland is a Scottish Charity based in Edinburgh, Scotland founded in 1793. The charity provides care, education and employment for people of all ages who are blind or partially sighted. Sight Scotland provides the following services: Royal Blind School, Forward Vision, Scottish Braille Press and Kidscene. Sight Scotland’s sister charity is Sight Scotland Veterans.

Macmilton "Mac" Marcoux is a Canadian Paralympic alpine skier who won three titles at the IPC Alpine Skiing World Cup at the age of 15. With guide Robin Femy, he won three medals in alpine skiing at the 2014 Winter Paralympics, including gold in the men's visually impaired giant slalom. He also has numerous awards including being inducted into the Sault Ste. Marie Walk of Fame. He has an older brother and a younger sister. He also enjoys riding BMX and mountain bikes.