An uprising of the Guelph faction in Milan led by Guido della Torre (hence also known as the Torriani faction) on 12 February 1311 was crushed by the troops of King Henry VII on the same day.

An uprising of the Guelph faction in Milan led by Guido della Torre (hence also known as the Torriani faction) on 12 February 1311 was crushed by the troops of King Henry VII on the same day.

Henry had arrived in Milan some weeks earlier, on 23 December 1310, [2] and had been crowned King of Italy on 6 January 1311. [3] The Tuscan Guelphs refused to attend the ceremony, and began preparing for resistance. Henry also rehabilitated the Visconti, the ousted former rulers of Milan, who returned from exile. Guido della Torre, who had thrown the Visconti out of Milan, objected and organised a revolt against Henry.

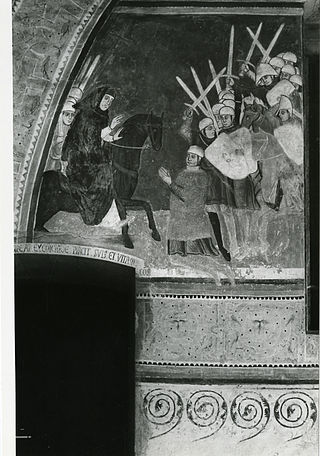

Around noon of 12 February, Duke Leopold of Austria, returning from a pleasure ride with few companions, was passing the Torriani quarter on his way back to his camp outside of Porta Comasina, northwest of the city, when he heard unusual noise of voices, weapons and horses, and through an open door he could see a congregation of men in full armour. Leopold sent his men back to his camp with the command to arm his followers, and went to king Henry, who was residing in the city palace, to warn him of the impending attack. Henry sent his brother Baldwin to fetch the German troops camped outside Porta Romana, southwest of the city, while a group of knights led by Henry of Flandres and John of Calcea rode to the Visconti palace and from there to the Torriani quarter, where they were immediately engaged in heavy combat. Henry remained in the palace, and ordered the palace gates to be barricaded, just in time before the arrival of an armed mob.

At the same time, the contingent of Teutonic Knights arrived, and in a single charge killed or dispersed most of the rebels. The German chronicles are unanimous in praising the bravery and valour of the knights in this attack, and especially their leader, the commander of Franconia and later Deutschmeister Konrad von Gundelfingen. The Austrian reinforcements had been delayed by barricades erected by the rebels at Porta Comasina. The Visconti reinforcement likewise arrived suspiciously late, in what was afterwards taken to imply at least passive support of the uprising. When the reinforcements arrived in the Torriani quarter, the fight there was mostly over. The soldiers now went on to loot the Torriani residences in a massacre that continued until nightfall. [1]

Guido della Torre escaped, and was condemned to death in absence by Henry. Archbishop Cassone della Torre was exiled.[ dubious ] Matteo I Visconti was also accused of supporting the uprising, mostly by his enemy John of Cermenate. Unlike Guido della Torre and his sons, who had escaped the city, Matteo Visconti appeared before Henry to receive judgement. The fact that his son Galeazzo had supported Leopold against the rebels counted in Matteo's favour. Both Matteo and Galeazzo were still briefly exiled from the city, suggesting that Henry was not fully convinced of their loyalty.

The Visconti were soon returned to power, however, with Henry appointing Matteo I Visconti as the Imperial vicar of Milan. [3] He also imposed his brother-in-law, Amadeus of Savoy, as the vicar-general in Lombardy. Wernher von Homberg was given the title of lieutenant general of Lombardy, and was given the right to collect the imperial tax at Flüelen.

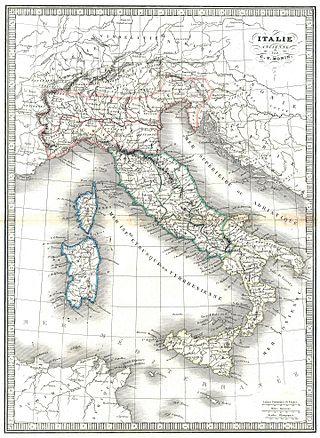

In the aftermath of the uprising, the Guelph cities of Northern Italy were turned against Henry, resisting the enforcement of his imperial claims on what had become communal lands and rights, and attempted to replace communal regulations with imperial laws. [4] Nevertheless, Henry managed to restore some semblance of imperial power in parts of northern Italy. Cities such as Parma, Lodi, Verona and Padua all accepted his rule. [3]

While German chronicles (such as Codex Balduini and Gesta Treverorum ) emphasise the valour of the German knights in the fight against the rebels, [1] Milanese historiography tended to depict the reprisals as the Germans unexpectedly assaulting the Torriani in their own homes. [5] An 1895 drawing by Lodovico Pogliaghi with the title "Assault on the houses of the Torriani in Milan" (assalto alle case dei Torriani a Milano, nel 1311) was included in Francesco Bertolini's Storia d'Italia. The Torriani houses damaged or destroyed by the Germans gave rise to the name case rotte ("broken houses") of that part of the city (modern Via Case Rotte, 45°28′01″N9°11′27″E / 45.4669°N 9.1909°E ).

Year 1311 (MCCCXI) was a common year starting on Friday of the Julian calendar.

The Visconti of Milan are a noble Italian family. They rose to power in Milan during the Middle Ages where they ruled from 1277 to 1447, initially as Lords then as Dukes, and several collateral branches still exist. The effective founder of the Visconti Lordship of Milan was the Archbishop Ottone, who wrested control of the city from the rival Della Torre family in 1277.

Leopold I, called The Glorious, was Duke of Austria and Styria – as co-ruler with his elder brother Frederick the Fair – from 1308 until his death. A member of the House of Habsburg, he was the third son of Albert I of Germany and Elisabeth of Gorizia-Tyrol, a scion of the Meinhardiner dynasty.

The Lord of Milan was a medieval noble title for the dynastic head of state of the city of Milan and surrounding countryside in northern Italy. From 1277 to 1395, Visconti of Milan family held the title, after which they were elevated to Duke of Milan.

The Castello Sforzesco is a medieval fortification located in Milan, Northern Italy. It was built in the 15th century by Francesco Sforza, Duke of Milan, on the remnants of a 14th-century fortification. Later renovated and enlarged, in the 16th and 17th centuries it was one of the largest citadels in Europe. Extensively rebuilt by Luca Beltrami in 1891–1905, it now houses several of the city's museums and art collections.

Martino della Torre was an Italian condottiero and statesman.

Giovanni Visconti (1290–1354) was an Italian Roman Catholic cardinal, who was co-ruler in Milan and lord of other Italian cities. He also was a military leader who fought against Florence, and used force to capture and hold other cities.

Ottone Visconti was Archbishop of Milan and Lord of Milan, the first of the Visconti line. Under his rule, the commune of Milan became a strong Ghibelline city and one of the Holy Roman Empire's seats in Italy.

The House of Della Torre were an Italian noble family who rose to prominence in Lombardy during the 12th–14th centuries, until they held the lordship of Milan before being ousted by the Visconti.

Milan, Italy is an ancient city in northern Italy first settled under the name Medhelanon in about 590 BC by a Celtic tribe belonging to the Insubres group and belonging to the Golasecca culture. The settlement was conquered by the Romans in 222 BC and renamed it Mediolanum. Diocletian divided the Roman Empire, choosing the eastern half for himself, making Milan the seat of the western half of the empire, from which Maximian ruled, in the late 3rd and early 4th century AD. In 313 AD Emperors Constantine and Licinius issued the Edict of Milan, which officially ended the persecution of Christians. In 774 AD, Milan surrendered to Charlemagne and the Franks.

The Battle of Desio was fought on 21 January 1277 between the Della Torre and Visconti families for the control of Milan and its countryside. The battlefield is located near the modern Desio, a commune outside the city in Lombardy, Northern Italy.

Napoleone della Torre, also known as Napo della Torre or Napo Torriani, was an Italian nobleman, who was effective Lord of Milan in the late 13th century. He was a member of the della Torre family, the father of Corrado della Torre and the brother of Raimondo della Torre.

Guido della Torre was a Lord of Milan between 1302 and 1312.

Henry VII, also known as Henry of Luxembourg, was Count of Luxembourg, King of Germany from 1308 and Holy Roman Emperor from 1312. He was the first emperor of the House of Luxembourg. During his brief career he reinvigorated the imperial cause in Italy, which was racked with the partisan struggles between the divided Guelph and Ghibelline factions, and inspired the praise of Dino Compagni and Dante Alighieri. He was the first emperor since the death of Frederick II in 1250, ending the Great Interregnum of the Holy Roman Empire; however, his premature death threatened to undo his life's work. His son, John of Bohemia, failed to be elected as his successor, and there was briefly another anti-king, Frederick the Fair, contesting the rule of Louis IV.

Bonacossa Borri, also known as Bonaca, or Bonaccossi Bonacosta (1254–1321), was Lady of Milan by marriage from 1269 to 1321.

Matteo I Visconti (1250–1322) was the second of the Milanese Visconti family to govern Milan. Matteo was born to Teobaldo Visconti and Anastasia Pirovano.

The following is a timeline of the history of the city of Milan, Italy.

Corrado della Torre, also called Mosca was an Italian medieval politician and condottiero, a member of the Torriani family.

Cassone della Torre, also called Mosca was an Italian medieval condottiero and feudal lord. A member of the Torriani family, he was Archbishop of Milan from 1308 to 1316 and patriarch of Aquileia from 1317 to 1318.

Palazzo Carmagnola is a palazzo quattrocentesco in Milano, which was remodelled several times in the following centuries. Historically belonging to the Sestiere di Porta Comasina, it is located in via Rovello 2.