Sofonisba Anguissola, also known as Sophonisba Angussola or Sophonisba Anguisciola, was an Italian Renaissance painter born in Cremona to a relatively poor noble family. She received a well-rounded education that included the fine arts, and her apprenticeship with local painters set a precedent for women to be accepted as students of art. As a young woman, Anguissola traveled to Rome where she was introduced to Michelangelo, who immediately recognized her talent, and to Milan, where she painted the Duke of Alba. The Spanish queen, Elizabeth of Valois, was a keen amateur painter and in 1559 Anguissola was recruited to go to Madrid as her tutor, with the rank of lady-in-waiting. She later became an official court painter to the king, Philip II, and adapted her style to the more formal requirements of official portraits for the Spanish court. After the queen's death, Philip helped arrange an aristocratic marriage for her. She moved to Sicily, and later Pisa and Genoa, where she continued to practice as a leading portrait painter.

Giorgio Giulio Clovio or Juraj Julije Klović was a Croatian-Italian illuminator, miniaturist, and painter born in the Kingdom of Croatia, who was mostly active in Renaissance Italy. He is considered the greatest illuminator of the Italian High Renaissance, and arguably the last very notable artist in the long tradition of the illuminated manuscript, before some modern revivals.

Lavinia Fontana was an Italian Mannerist painter active in Bologna and Rome. She is best known for her successful portraiture, but also worked in the genres of mythology and religious painting. She was trained by her father, Prospero Fontana. She is regarded as the first female career artist in Western Europe, as she relied on commissions for her income. Her family relied on her career as a painter, and her husband served as her agent and raised their 11 children. She was perhaps the first female artist to paint female nudes, but this is a topic of controversy among art historians.

Lucia Anguissola was an Italian Mannerist painter of the late Renaissance. Born in Cremona, Italy, she was the third daughter among the seven children of Amilcare Anguissola and Bianca Ponzoni. Her father was a member of the Genoese minor nobility and encouraged his five daughters to develop artistic skills alongside their humanist education. Lucia most likely trained with her renowned eldest sister Sofonisba Anguissola. Her paintings, mainly portraits, are similar in style and technique to those of her sister. Contemporary critics considered her skill exemplary; according to seventeenth-century biographer Filippo Baldinucci, Lucia had the potential to "become a better artist than even Sofonisba" had she not died so young.

A court painter was an artist who painted for the members of a royal or princely family, sometimes on a fixed salary and on an exclusive basis where the artist was not supposed to undertake other work. Painters were the most common, but the court artist might also be a court sculptor. In Western Europe, the role began to emerge in the mid-13th century. By the Renaissance, portraits, mainly of the family, made up an increasingly large part of their commissions, and in the early modern period one person might be appointed solely to do portraits, and another for other work, such as decorating new buildings.

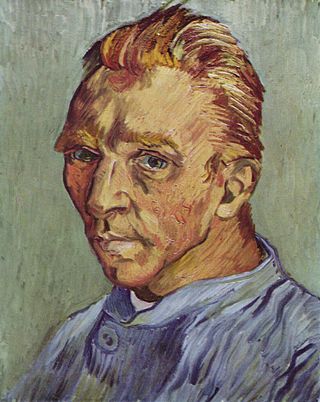

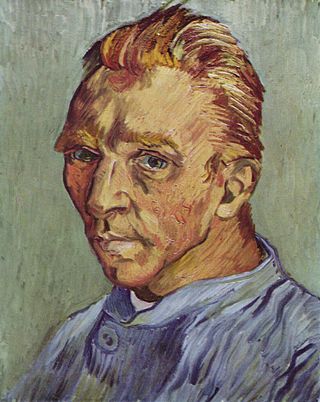

A self-portrait is a portrait of an artist made by themselves. Although self-portraits have been made since the earliest times, the practice of self-portraiture only gaining momentum in the Early Renaissance in the mid-15th century that artists can be frequently identified depicting themselves as either the main subject, or as important characters in their work. With better and cheaper mirrors, and the advent of the panel portrait, many painters, sculptors and printmakers tried some form of self-portraiture. Portrait of a Man in a Turban by Jan van Eyck of 1433 may well be the earliest known panel self-portrait. He painted a separate portrait of his wife, and he belonged to the social group that had begun to commission portraits, already more common among wealthy Netherlanders than south of the Alps. The genre is venerable, but not until the Renaissance, with increased wealth and interest in the individual as a subject, did it become truly popular.

Fede Galizia, better known as Galizia, was an Italian painter of still-lifes, portraits, and religious pictures. She is especially noted as a painter of still-lifes of fruit, a genre in which she was one of the earliest practitioners in European art. She is perhaps not as well known as other female artists, such as Angelica Kauffman and Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, because she did not have access to court-oriented or aristocratic social circles, nor had she sought the particular patronage of political rulers and noblemen.

Events from the year 1550 in art.

Self-portrait by Judith Leyster is a Dutch Golden Age painting in oils now in the collection of the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC. It was offered in 1633 as a masterpiece to the Haarlem Guild of St. Luke. It was attributed for centuries to Frans Hals and was only properly attributed to Judith Leyster upon acquisition by the museum in 1949. The style is indeed comparable to that of Hals, Haarlem's most famous portraitist.

Portrait of the Artist's Family is a 1558–59 oil-on-canvas painting by the Italian artist Sofonisba Anguissola in the Nivaagaard art gallery, in Copenhagen.

Self-Portrait as a Lute Player is one of many self-portrait paintings made by the Italian baroque artist Artemisia Gentileschi. It was created between 1615 and 1617 for the Medici family in Florence. Today, it hangs in the Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art, Hartford, Connecticut, US. It shows the artist posing as a lute player looking directly at the audience. The painting has symbolism in the headscarf and outfit that portray Gentileschi in a costume that resembles a Romani woman. Self-Portrait as a Lute Player has been interpreted as Gentileschi portraying herself as a knowledgeable musician, a self portrayal as a prostitute, and as a fictive expression of one aspect of her identity.

Elena Anguissola was an Italian painter and nun. She was the sister of the better-known painter Sofonisba Anguissola.

The Game of Chess is an oil-on-canvas painting executed ca. 1555 by Italian Renaissance artist Sofonisba Anguissola. Anguissola was 23 years old when she painted it.

Anna Maria Anguissola was a 16th-century Italian painter born in Cremona, Italy.

Self-portrait at an Easel is an oil-on-canvas painting created c. 1556–1565 by the Italian Renaissance painter Sofonisba Anguissola, now in Łańcut Castle. From the same era as Self-Portrait at a Spinet (Naples) it shows the artist painting a devotional canvas and is one of a group of self-portraits which also includes Self-Portrait (Vienna) and Miniature Self Portrait (Boston).

Self-Portrait is a small oil-on-panel painting by the Italian artist Sofonisba Anguissola, signed and dated 1554 on the open book held by the artist. The portrait is now in the Kunsthistorisches Museum, in Vienna.

Portrait of Elisabeth of Valois is an oil-on-canvas painting executed c.1561–1565 by the Italian artist Sofonisba Anguissola, now in the Museo del Prado, in Madrid.

Sofonisba Anguissola's Portrait of Massimiliano II Stampa, painted in 1557, captures a young nobleman dressed in elaborate court attire, symbolizing his inheritance of the Marchese of Soncino title. The inscription on the reverse of the canvas, revealed during a 1983 conservation, identified the subject as Massimiliano II, age nine, and the third marchese of Soncino. The painting includes a sleeping dog beside him, reflecting the Renaissance tradition of using animals as symbols of loyalty and virtue. The painting’s journey through various owners before settling at the Walters Art Museum in 1931 adds to its historical intrigue. Anguissola, one of the Renaissance's few celebrated female artists, is renowned for her insightful and detailed portraits, with this piece standing as one of her major early commissions. Despite the challenges faced by female artists during the period, Anguissola’s work, including this portrait, has gained recognition for its technical skill and symbolic depth.

Female self-portrait in painting is the representation of a person of the female gender painted by herself.

Bernardino Campi Painting Sofonisba Anguissola is an oil on canvas painting from the late 1550s by one of the most important woman artists of the Italian Renaissance, Sofonisba Anguissola. It is a double portrait in which Anguissola has painted a self-portrait as if it were a canvas being painted by her teacher, Bernardino Campi. Despite not being physically present in the scene, Anguissola established herself as the primary subject of the piece by making the self-portrait appear larger than the artist. Witney Chadwick has called this "the first historical example of the woman artist consciously collapsing the subject-object position." Mary Garrard has noted that this is an important example of what Giorgio Vasari termed a "breathing likeness."