Related Research Articles

In Greek mythology, Agamemnon was a king of Mycenae, the son, or grandson, of King Atreus and Queen Aerope, the brother of Menelaus, the husband of Clytemnestra and the father of Iphigenia, Electra or Laodike (Λαοδίκη), Orestes and Chrysothemis. Legends make him the king of Mycenae or Argos, thought to be different names for the same area. When Menelaus's wife, Helen, was taken to Troy by Paris, Agamemnon commanded the united Greek armed forces in the ensuing Trojan War.

Aegisthus was a figure in Greek mythology. Aegisthus is known from two primary sources: the first is Homer's Odyssey, believed to have been first written down by Homer at the end of the 8th century BC, and the second from Aeschylus's Oresteia, written in the 5th century, BC.

In Greek mythology, Atreus was a king of Mycenae in the Peloponnese, the son of Pelops and Hippodamia, and the father of Agamemnon and Menelaus. Collectively, his descendants are known as Atreidai or Atreidae.

In Greek mythology, Aerope was the daughter of Catreus, king of Crete, and sister to Clymene, Apemosyne and Althaemenes. Aerope's father Catreus gave her to Nauplius, to be drowned, or sold abroad, but Nauplius spared her, and she became the wife of Atreus, or Pleisthenes, and by most accounts the mother of Agamemnon and Menelaus. While the wife of Atreus, she became the lover of his brother Thyestes, and gave Thyestes the golden lamb, by which he became the king of Mycenae.

In Greek mythology, Thyestes was a king of Olympia. Thyestes and his brother, Atreus, were exiled by their father for having murdered their half-brother, Chrysippus, in their desire for the throne of Olympia. They took refuge in Mycenae, where they ascended the throne upon the absence of King Eurystheus, who was fighting the Heracleidae. Eurystheus had meant for their lordship to be temporary; it became permanent because of his death in conflict.

In Greek mythology, Pleisthenes or Plisthenes, is the name of several members of the house of Tantalus, the most important being a son of Atreus, said to be the father of Agamemnon and Menelaus. Although these two brothers are usually considered to be the sons of Atreus himself, according to some accounts, Pleisthenes was their father, but he died, and Agamemnon and Menelaus were adopted by their grandfather Atreus.

In Greek mythology, Pelops was king of Pisa in the Peloponnesus region. His father, Tantalus, was the founder of the House of Atreus through Pelops's son of that name.

Hippodamia was a Greek mythological figure. She was the queen of Pisa as the wife of Pelops.

In Greek mythology, Chrysippus was a divine hero of Elis in the Peloponnesus (Greece), sometimes referred to as Chrysippus of Pisa.

Exekias was an ancient Greek vase-painter and potter who was active in Athens between roughly 545 BC and 530 BC. Exekias worked mainly in the black-figure technique, which involved the painting of scenes using a clay slip that fired to black, with details created through incision. Exekias is regarded by art historians as an artistic visionary whose masterful use of incision and psychologically sensitive compositions mark him as one of the greatest of all Attic vase painters. The Andokides painter and the Lysippides Painter are thought to have been students of Exekias.

The Kleophon Painter is the name given to an anonymous Athenian vase painter in the red-figure style who flourished in the mid-to-late 5th century BC. He is thus named because one of the works attributed to him bears an inscription in praise of a youth named "Kleophon". He appears to have been originally from the workshop of Polygnotos, and in turn to have taught the so-called Dinos Painter. Three vases suggest a collaboration with the Achilles Painter, while a number of black-figure works have also been attributed to him by some scholars.

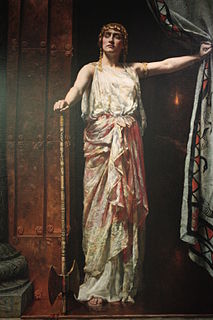

Clytemnestra, in Greek mythology, was the wife of Agamemnon, king of Mycenae, and the sister of Helen of Troy. In Aeschylus' Oresteia, she murders Agamemnon – said by Euripides to be her second husband – and the Trojan princess Cassandra, whom Agamemnon had taken as a war prize following the sack of Troy; however, in Homer's Odyssey, her role in Agamemnon's death is unclear and her character is significantly more subdued.

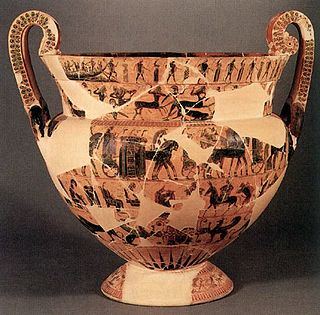

The François Vase is a large Attic volute krater decorated in the black-figure style. It stands at 66 cm in height and was inspired by earlier bronze vases. It was used for wine. A milestone in the development of ancient Greek pottery due to the drawing style used as well as the combination of related stories depicted in the numerous friezes, it is dated to circa 570/560 BCE. The Francois Vase was discovered in 1844 in Chiusi where an Etruscan tomb in the necropolis of Fonte Rotella was found located in central Italy. It was named after its discoverer Alessandro François, it is now in the Museo Archeologico at Florence. It remains uncertain whether the krater was used in Greece or in Etruria, and whether the handles were broken and repaired in Greece or in Etruria. Perhaps the François Vase was made for a symposium given by a member of an aristocratic family in Solonian Athens, then broken and, after being carefully repaired, was sent to Etruria, perhaps as an instance of elite-gift exchange. It bears the inscriptions Ergotimos mepoiesen and Kleitias megraphsen, meaning 'Ergotimos made me' and 'Kleitias painted me'. It depicts 270 figures, 121 of which have accompanying inscriptions which is highly unusual for so many to be identified; the scenes depicted represent a number of mythological themes. In 1900 the vase was smashed into 638 pieces by a museum guard by hurling a wooden stool against the protective glass. It was later restored by Pietro Zei in 1902, followed by a second reconstruction in 1973 incorporating previously missing pieces.

The Pan Painter was an ancient Greek vase-painter of the Attic red-figure style, probably active c. 480 to 450 BCE. John Beazley attributed over 150 vases to his hand in 1912:

"Cunning composition; rapid motion; quick deft draughtsmanship; strong and peculiar stylisation; a deliberate archaism, retaining old forms, but refining, refreshing, and galvanizing them; nothing noble or majestic, but grace, humour, vivacity, originality, and dramatic force: these are the qualities which mark the Boston krater, and which characterize the anonymous artist who, for the sake of convenience, may be called the 'master of the Boston Pan-vase', or, more briefly, 'the Pan-master'."

In Greek mythology, Thesprotus may refer to two individuals:

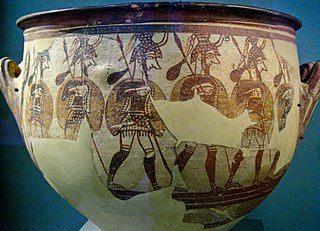

The Mycenaean Warrior Vase, found by Heinrich Schliemann on the acropolis of Mycenae, is one of the prominent treasures of the National Archaeological Museum, Athens. The Warrior Vase, dated to the 12th century BCE, is probably the best-known piece of Late Helladic pottery. It is a krater, a mixing bowl used for the dilution of wine with water, a custom which the ancient Greeks believed to be a sign of civilized behavior.

The calyx-krater by the artist called the "Painter of the Berlin Hydria" depicting an Amazonomachy is an ancient Greek painted vase in the red figure style, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. It is a krater, a bowl made for mixing wine and water, and specifically a calyx-krater, where the bowl resembles the calyx of a flower. Vessels such as these were often used at a symposion, which was an elite party for drinking.

Ancient Greek funerary vases are decorative grave markers made in ancient Greece that were designed to resemble liquid-holding vessels. These decorated vases were placed on grave sites as a mark of elite status. There are many types of funerary vases, such as amphorae, kraters, oinochoe, and kylix cups, among others. One famous example is the Dipylon amphora. Every-day vases were often not painted, but wealthy Greeks could afford luxuriously painted ones. Funerary vases on male graves might have themes of military prowess, or athletics. However, allusions to death in Greek tragedies was a popular motif. Famous centers of vase styles include Corinth, Lakonia, Ionia, South Italy, and Athens.

The Athenian Band Cup is an Attic Greek kylix attributed to the Oakeshott Painter. It is further classified as a band cup, a type of Little-Master cup.

In Greek mythology, Pelopia, less commonly known as Mnesiphae, was the daughter of Thyestes.

References

- ↑ Taplin, Oliver (2007). Pots & plays : interactions between tragedy and Greek vase-painting of the fourth century B.C. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum. p. 320. ISBN 978-0892368075.

- ↑ "Mixing bowl (calyx-krater)". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. Retrieved 28 April 2016.

- ↑ Neer, Richard T. (2012). Greek art and archaeology : a new history, c. 2500-c. 150 BCE. New York, NY: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0500288771.

- ↑ "FABLES 50 - 99, TRANSLATED BY MARY GRANT" . Retrieved 29 April 2016.

- ↑ Vermeule, Emily (28 February 2013). "Baby Aigisthos and the Bronze Age". Proceedings of the Cambridge Philological Society. 33: 122–152. doi:10.1017/S006867350000496X.