A monster is a type of fictional creature found in horror, fantasy, science fiction, folklore, mythology and religion. They are very often depicted as dangerous and aggressive, with a strange or grotesque appearance that causes terror and fear, often in humans. Monsters usually resemble bizarre, deformed, otherworldly and/or mutated animals or entirely unique creatures of varying sizes, but may also take a human form, such as mutants, ghosts, spirits, zombies, or cannibals, among other things. They may or may not have supernatural powers, but are usually capable of killing or causing some form of destruction, threatening the social or moral order of the human world in the process.

In Greek mythology, Talos, also spelled Talus or Talon, was a man of bronze who protected Crete from pirates and invaders. Despite the popular idea that he was a giant, no ancient source states this explicitly.

Psychological horror is a subgenre of horror and psychological fiction with a particular focus on mental, emotional, and psychological states to frighten, disturb, or unsettle its audience. The subgenre frequently overlaps with the related subgenre of psychological thriller, and often uses mystery elements and characters with unstable, unreliable, or disturbed psychological states to enhance the suspense, horror, drama, tension, and paranoia of the setting and plot and to provide an overall creepy, unpleasant, unsettling, or distressing atmosphere.

A merman, the male counterpart of the mythical female mermaid, is a legendary creature which is human from the waist up and fish-like from the waist down, but may assume normal human shape. Sometimes mermen are described as hideous and other times as handsome.

Lamia, in ancient Greek mythology, was a child-eating monster and, in later tradition, was regarded as a type of night-haunting spirit or "daimon".

Ambroise Paré was a French barber surgeon who served in that role for kings Henry II, Francis II, Charles IX and Henry III. He is considered one of the fathers of surgery and modern forensic pathology and a pioneer in surgical techniques and battlefield medicine, especially in the treatment of wounds. He was also an anatomist, invented several surgical instruments, and was a member of the Parisian barber surgeon guild.

Mary Dyer was an English and colonial American Puritan-turned-Quaker who was hanged in Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony, for repeatedly defying a Puritan law banning Quakers from the colony. She is one of the four executed Quakers known as the Boston martyrs.

The Battle of Ravenna, fought on 11 April 1512, was a major battle of the War of the League of Cambrai. It pitted forces of the Holy League against France and their Ferrarese allies. Although the French and Ferrarese eliminated the Papal–Spanish forces as a serious threat, their triumph was overshadowed by the loss of their young general Gaston of Foix. The victory therefore did not help them secure northern Italy. The French withdrew entirely from Italy in the summer of 1512, as Swiss mercenaries hired by Pope Julius II and Imperial troops under Emperor Maximilian I arrived in Lombardy. The Sforza were restored to power in Milan.

"The House of Asterion" is a short story by Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges. The story was first published in 1947 in the literary magazine Los Anales de Buenos Aires and republished in Borges's short story collection The Aleph in 1949. It is based on the Greek myth of Theseus and the Minotaur and is told from the perspective of Asterion, the Minotaur.

Theodore M. Porter is a historian of science emeritus in the Department of History at UCLA. He is known for his histories of statistical thinking and quantification, particularly the sociology of quantification.

Barbara Creed is a professor of cinema studies in the School of Culture and Communication at the University of Melbourne. She is the author of six books on gender, feminist film theory, and the horror genre. Creed is a graduate of Monash and La Trobe universities where she completed doctoral research using the framework of psychoanalysis and feminist theory to examine horror films. She is known for her cultural criticism.

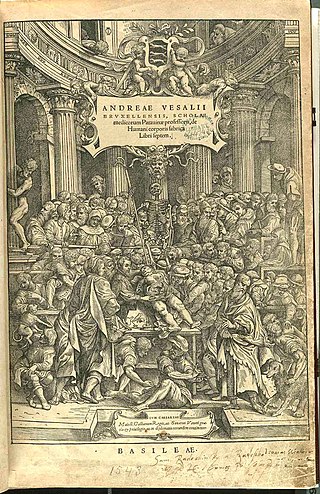

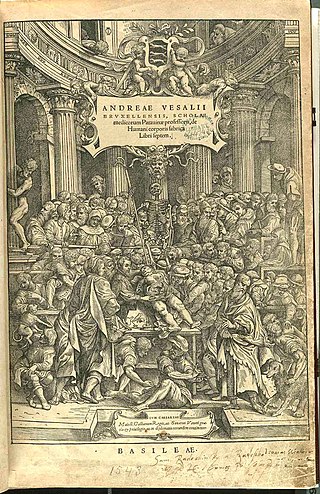

The Medical Renaissance, from around 1400 to 1700 CE, was a period of progress in European medical knowledge, with renewed interest in the ideas of the ancient Greek, Roman civilizations and Islamic medicine, following the translation into Medieval Latin of many works from these societies. Medical discoveries during the Medical Renaissance are credited with paving the way for modern medicine.

In late Classical Greek art, an ichthyocentaur was a centaurine sea being with the upper body of a human, the lower anterior half and fore-legs of a horse, and the tailed posterior half of a fish. The earliest example dates to the 2nd century BC, among the friezes in the Pergamon Altar. There are further examples of Aphros and/or Bythos, the personifications of foam and abyss, respectively, depicted as ichthyocentaurs in mosaics and sculptures.

Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus is an 1818 Gothic novel written by English author Mary Shelley. Frankenstein tells the story of Victor Frankenstein, a young scientist who creates a sapient creature in an unorthodox scientific experiment. Shelley started writing the story when she was 18, and the first edition was published anonymously in London on 1 January 1818, when she was 20. Her name first appeared in the second edition, which was published in Paris in 1821.

Historia animalium, published in Zurich in 1551–1558 and 1587, is an encyclopedic "inventory of renaissance zoology" by Conrad Gessner (1516–1565). Gessner was a medical doctor and professor at the Carolinum in Zürich, the precursor of the University of Zurich. The Historia animalium, after Aristotle's work of the same name, is the first modern zoological work that attempts to describe all the animals known, and the first bibliography of natural history writings. The five volumes of natural history of animals cover more than 4500 pages. The animals are presented in alphabetical order, marking the change from Middle Ages encyclopedias, or "mirrors" to a modern view of a consultation work.

A monstrous birth, variously defined in history, is a birth in which a defect renders the animal or human child malformed to such a degree as to be considered "monstrous". Such births were often taken as omens, signs of God, or moral warnings to be wielded by society at large as a tool for manipulation in various ways. The development of the field of obstetrics helped do away with spurious associations with evil but the historical significance of these fetuses remains noteworthy. In early and medieval Christianity, monstrous births were presented as and used to pose difficult theological problems about humanity and salvation.

The representation of gender in horror films, particularly depictions of women, has been the subject of critical commentary.

Physica Curiosa written by scholar, Jesuit priest and scientist Gaspar Schott is a seventeenth century encyclopedia, published first in 1662, is divided into twelve books and has been richly illustrated with prints of copper engravings. It is the first part of a two-volume work, the other being Technica Curiosa, published in 1664.

The Portrait of Antonietta Gonzales is a portrait by one of the most important Italian Renaissance women artists, Lavinia Fontana. The portrait is oil on canvas and depicts a girl with hypertrichosis named Antonietta Gonzales, daughter of Petrus Gonsalvus. Antonietta is dressed in finery to show her noble status, but as someone who would have been ostracized because of her unusual appearance, she would have been seen as more animal than human and would not have had the same freedoms as other courtiers.