Related Research Articles

Thomas Woodrow Wilson was the 28th president of the United States, serving from 1913 to 1921. He was the only Democrat to serve as president during the Progressive Era when Republicans dominated the presidency and legislative branches. As president, Wilson changed the nation's economic policies and led the United States into World War I. He was the leading architect of the League of Nations, and his stance on foreign policy came to be known as Wilsonianism.

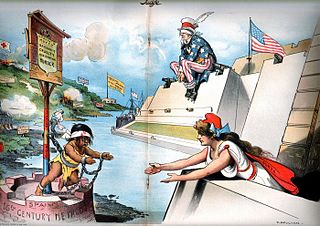

In the history of United States foreign policy, the Roosevelt Corollary was an addition to the Monroe Doctrine articulated by President Theodore Roosevelt in his 1904 State of the Union Address, largely as a consequence of the Venezuelan crisis of 1902–1903. The corollary states that the United States could intervene in the internal affairs of Latin American countries if they committed flagrant wrongdoings that "loosened the ties of civilized society".

The Good Neighbor policy was the foreign policy of the administration of United States President Franklin D. Roosevelt towards Latin America. Although the policy was implemented by the Roosevelt administration, President Woodrow Wilson had previously used the term, but subsequently went on to justify U.S. involvement in the Mexican Revolution and occupation of Haiti. Senator Henry Clay had coined the term Good Neighbor in the previous century. President Herbert Hoover turned against interventionism and developed policies that Roosevelt perfected.

American exceptionalism is the belief that the United States is either distinctive, unique, or exemplary compared to other nations. Proponents argue that the values, political system, and historical development of the U.S. are unique in human history, often with the implication that it is both destined and entitled to play a distinct and positive role on the world stage.

José Victoriano Huerta Márquez was a general in the Mexican Federal Army and 39th President of Mexico, who came to power by coup against the democratically elected government of Francisco I. Madero with the aid of other Mexican generals and the U.S. Ambassador to Mexico. His violent seizure of power set off a new wave of armed conflict in the Mexican Revolution.

The Tampico Affair began as a minor incident involving United States Navy sailors and the Mexican Federal Army loyal to Mexican dictator General Victoriano Huerta. On April 9, 1914, nine sailors had come ashore to secure supplies and were detained by Mexican forces. Commanding Admiral Henry Mayo demanded that the US sailors be released, and that Mexico issue an apology, raise and salute the US flag, and perform a 21-gun salute. Mexico refused the demand. US President Woodrow Wilson backed the demand, and the conflict escalated when the Americans occupied the port city of Veracruz for more than six months. This contributed to the fall of Huerta, who resigned in July 1914. Since the US had not had diplomatic relations with Mexico since Huerta's seizure of power in 1913, the ABC powers Argentina, Brazil, and Chile offered to mediate the conflict, in the Niagara Falls peace conference, held in Canada. The American occupation of Veracruz caused widespread anti-American sentiment.

Henry Lane Wilson was an American attorney, journalist, and diplomat who served successively as United States Minister to Chile (1897–1904), Minister to Belgium (1905–09), and Ambassador to Mexico (1909–13). He is best known to history for his involvement in the February 1913 coup d'etat which deposed and assassinated President of Mexico Francisco I. Madero, for which he remains controversial and "perhaps the most vilified United States official of [the 20th] century" in Mexico.

Gunboat diplomacy is the pursuit of foreign policy objectives with the aid of conspicuous displays of naval power, implying or constituting a direct threat of warfare should terms not be agreeable to the superior force.

Wilsonianism, or Wilsonian idealism, is a certain type of foreign policy advice. The term comes from the ideas and proposals of United States President Woodrow Wilson. He issued his famous Fourteen Points in January 1918 as a basis for ending World War I and promoting world peace. He was a leading advocate of the League of Nations to enable the international community to avoid wars and end hostile aggression. Wilsonianism is a form of liberal democratic internationalism.

The Banana Wars were a series of conflicts that consisted of military occupation, police action, and intervention by the United States in Central America and the Caribbean between the end of the Spanish–American War in 1898 and the inception of the Good Neighbor Policy in 1934. The military interventions were primarily carried out by the United States Marine Corps, which also developed a manual, the Small Wars Manual (1921), based on their experiences. On occasion, the United States Navy provided gunfire support and the United States Army also deployed troops.

Dollar diplomacy of the United States, particularly during the presidency of William Howard Taft (1909–1913) was a form of American foreign policy to minimize the use or threat of military force and instead further its aims in Latin America and East Asia through the use of its economic power by guaranteeing loans made to foreign countries. In his message to Congress on 3 December 1912, Taft summarized the policy of Dollar diplomacy:

The United States involvement in the Mexican Revolution was varied and seemingly contradictory, first supporting and then repudiating Mexican regimes during the period 1910–1920. For both economic and political reasons, the U.S. government generally supported those who occupied the seats of power, but could withhold official recognition. The U.S. supported the regime of Porfirio Díaz after initially withholding recognition since he came to power by coup. In 1909, Díaz and U.S. President Taft met in Ciudad Juárez, across the border from El Paso, Texas. Prior to Woodrow Wilson's inauguration on March 4, 1913, the U.S. Government focused on just warning the Mexican military that decisive action from the U.S. military would take place if lives and property of U.S. nationals living in the country were endangered. President William Howard Taft sent more troops to the US-Mexico border but did not allow them to intervene directly in the conflict, a move which Congress opposed. Twice during the Revolution, the U.S. sent troops into Mexico, to occupy Veracruz in 1914 and to northern Mexico in 1916 in a failed attempt to capture Pancho Villa. U.S. foreign policy toward Latin America was to assume the region was the sphere of influence of the U.S., articulated in the Monroe Doctrine. However the U.S. role in the Mexican Revolution has been exaggerated. It did not directly intervene in the Mexican Revolution in a sustained manner.

The presidency of Woodrow Wilson began on March 4, 1913, when Woodrow Wilson was inaugurated as the 28th President of the United States, and ended on March 4, 1921. He took office after defeating incumbent President William Howard Taft and former President Theodore Roosevelt in the 1912 presidential election. Wilson was a Democrat, who previously served as governor of New Jersey. He gained a large majority in the electoral vote and a 42% plurality of the popular vote in a four-candidate field. Wilson was re-elected in 1916 by a narrow margin. Despite his New Jersey base, most Southern leaders worked with him as a fellow Southerner. Wilson experienced several strokes in the last year and a half of his presidency causing him to be largely incapacitated. He was succeeded by Republican Warren G. Harding, who won the 1920 election.

Missionary diplomacy was the policy of US President Woodrow Wilson that Washington had a moral responsibility to deny diplomatic recognition to any Latin American government that was not democratic. It was an expansion of President James Monroe's 1823 Monroe Doctrine.

The Ypiranga Incident occurred on April 21, 1914, at the port of Veracruz in Mexico during the Mexican Revolution. Ypiranga was a German steamship that was commissioned to transport arms and munitions to the Mexican federal government under Victoriano Huerta. The United States had placed Mexico under an arms embargo to stifle the flow of weaponry to the war-torn state, then in the throes of civil war, forcing Huerta's government to look to Europe and Japan for armaments.

The United States entered into World War I on 6 April 1917, more than two and a half years after the war began in Europe.

The Empire of Liberty is a theme developed first by Thomas Jefferson to identify what he considered the responsibility of the United States to spread freedom across the world. Jefferson saw the mission of the U.S. in terms of setting an example, expansion into western North America, and by intervention abroad. Major exponents of the theme have been James Monroe, Andrew Jackson and James K. Polk, Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson (Wilsonianism), Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry Truman, Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, and George W. Bush.

History of the United States foreign policy is a brief overview of major trends regarding the foreign policy of the United States from the American Revolution to the present. The major themes are becoming an "Empire of Liberty", promoting democracy, expanding across the continent, supporting liberal internationalism, contesting World Wars and the Cold War, fighting international terrorism, developing the Third World, and building a strong world economy with low tariffs.

The history of U.S. foreign policy from 1913–1933 covers the foreign policy of the United States during World War I and much of the Interwar period. The administrations of Presidents Woodrow Wilson, Warren G. Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover successively handled U.S. foreign policy during this period.

The foreign policy under the presidency of Woodrow Wilson deals with American diplomacy, and political, economic, military, and cultural relationships with the rest of the world from 1913 to 1921. Although Wilson had no experience in foreign policy, he made all the major decisions, usually with the top advisor Edward M. House. His foreign policy was based on his messianic philosophical belief that America had the utmost obligation to spread its principles while reflecting the 'truisms' of American thought.

References

- 1 2 Woodrow Wilson's Address at Independence Hall: "The Meaning of Liberty July 4, 1914 Address http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/index.php?pid=65381

- ↑ "Moral Diplomacy | Justice and Government". Archived from the original on 2013-07-10. Retrieved 2013-06-06.

- ↑ "Wilson and Moral Diplomacy". Archived from the original on 2007-05-10.

- ↑ Winfried Fluck et al (2011). Re-Framing the Transnational Turn in American Studies. UP New England. p. 207.

- ↑ de Tocqueville, Alexis. Democracy in America (1840), part 2, page 36: "The position of the Americans is therefore quite exceptional, and it may be believed that no other democratic people will ever be placed in a similar one."

- ↑ Paul Horgan, Great River: the Rio Grande in North American History (Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 1984), 913