A Christogram is a monogram or combination of letters that forms an abbreviation for the name of Jesus Christ, traditionally used as a religious symbol within the Christian Church.

A rood or rood cross, sometimes known as a triumphal cross, is a cross or crucifix, especially the large crucifix set above the entrance to the chancel of a medieval church. Alternatively, it is a large sculpture or painting of the crucifixion of Jesus.

The Gero Cross or Gero Crucifix, of around 965–970, is the oldest large sculpture of the crucified Christ north of the Alps, and has always been displayed in Cologne Cathedral in Germany. It was commissioned by Gero, Archbishop of Cologne, who died in 976, thus providing a terminus ante quem for the work. It is carved in oak, and painted and partially gilded – both have been renewed. The halo and cross-pieces are original, but the Baroque surround was added in 1683. The figure is 187 cm high, and the span of its arms is 165 cm. It is the earliest known Western depiction of Christ on the cross while dead; earlier depictions had Christ appearing alive.

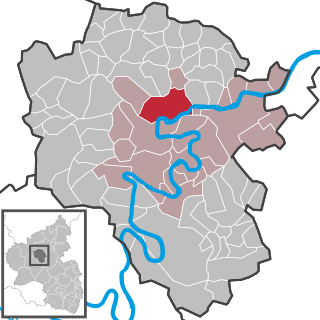

Klotten is an Ortsgemeinde – a municipality belonging to a Verbandsgemeinde, a kind of collective municipality – in the Cochem-Zell district in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It belongs to the Verbandsgemeinde of Cochem, whose seat is in the like-named town. It is a winemaking centre.

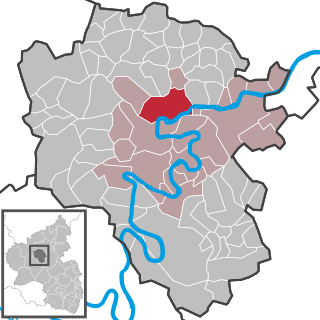

Moselkern is an Ortsgemeinde – a municipality belonging to a Verbandsgemeinde, a kind of collective municipality – in the Cochem-Zell district in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It belongs to the Verbandsgemeinde of Cochem.

Müden an der Mosel is an Ortsgemeinde – a municipality belonging to a Verbandsgemeinde, a kind of collective municipality – and a tourism resort in the Cochem-Zell district in Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany. It belongs to the Verbandsgemeinde of Cochem.

Crucifixions and crucifixes have appeared in the arts and popular culture from before the era of the pagan Roman Empire. The crucifixion of Jesus has been depicted in a wide range of religious art since the 4th century CE, frequently including the appearance of mournful onlookers such as the Virgin Mary, Pontius Pilate, and angels, as well as antisemitic depictions portraying Jews as responsible for Christ's death. In more modern times, crucifixion has appeared in film and television as well as in fine art, and depictions of other historical crucifixions have appeared as well as the crucifixion of Christ. Modern art and culture have also seen the rise of images of crucifixion being used to make statements unconnected with Christian iconography, or even just used for shock value.

The basalt cross is a particular type of stone cross found in the Eifel mountains of Germany, bearing witness to the piety of the local population in times past. These crosses indicate their beliefs as well as the wealth and standing of the people who erected them. Details such as accidents, occupations and prayer requests have survived, thanks to the extremely weather-resistant material of which the crosses are made. Their geographic distribution is centred on the basalt quarries of Mayen and Mendig, and covers an area with a radius of approximately 30 kilometres between the Rhine, Ahr and Moselle rivers. The exact number of monuments is not known. Local historian, Kurt Müller-Veltin, estimates that there are about 4,500 wayside crosses and about 6,000 grave crosses. The conservation of these monuments is undertaken by the Rhenisch Society for Monument Conservation.

A forked cross, is a Gothic cross in the form of the letter Y that is also known as a crucifixus dolorosus, furca, ypsilon cross, Y-cross, robber's cross or thief's cross.

The Cross of Mathilde is an Ottonian processional cross in the crux gemmata style which has been in Essen in Germany since it was made in the 11th century. It is named after Abbess Mathilde who is depicted as the donor on a cloisonné enamel plaque on the cross's stem. It was made between about 1000, when Mathilde was abbess, and 1058, when Abbess Theophanu died; both were princesses of the Ottonian dynasty. It may have been completed in stages, and the corpus, the body of the crucified Christ, may be a still later replacement. The cross, which is also called the "second cross of Mathilde", forms part of a group along with the Cross of Otto and Mathilde or "first cross of Mathilde" from late in the preceding century, a third cross, sometimes called the Senkschmelz Cross, and the Cross of Theophanu from her period as abbess. All were made for Essen Abbey, now Essen Cathedral, and are kept in Essen Cathedral Treasury, where this cross is inventory number 4.

The Bernward Column also known as the Christ Column is a bronze column, made c. 1020 for St. Michael's Church in Hildesheim, Germany, and regarded as a masterpiece of Ottonian art. It was commissioned by Bernward, the thirteenth bishop of Hildesheim in 1020, and made at the same time. It depicts images from the life of Jesus, arranged in a helix similar to Trajan's Column: it was originally topped with a cross or crucifix. During the 19th century, it was moved to a courtyard and later to Hildesheim Cathedral. During the restoration of the cathedral from 2010 to 2014, it was moved back to its original location in St. Michael's, but was returned to the Cathedral in August 2014.

The Christian cross, with or without a figure of Christ included, is the main religious symbol of Christianity. A cross with a figure of Christ affixed to it is termed a crucifix and the figure is often referred to as the corpus.

The Magdeburg Ivories are a set of 16 surviving ivory panels illustrating episodes of Christ's life. They were commissioned by Emperor Otto I, probably to mark the dedication of Magdeburg Cathedral, and the raising of the Magdeburg see to an archbishopric in 968. The panels were initially part of an unknown object in the cathedral that has been variously conjectured to be an antependium or altar front, a throne, door, pulpit, or an ambon; traditionally this conjectural object, and therefore the ivories as a group, has been called the Magdeburg Antependium. This object is believed to have been dismantled or destroyed in the 1000s, perhaps after a fire in 1049.

The Přemyslid Crucifix is a polychromed wooden cross from Jihlava dating from the first half of the 14th century. It is on display at the Picture Gallery of Strahov Monastery in Prague. In 2010, it was declared a national cultural monument by the Czech government.

The term Crucifixion plaque refers to small early medieval sculptures with a central panel of the still alive but crucified Jesus surrounded by four smaller ancillary panels, consisting of Stephaton and Longinus in the lower quadrants, and two hovering attendant angels in the quadrants above his arms. Notable examples are found in classical Roman and 8th to mid-12th century Irish Insular art.

The Clonmacnoise Crucifixion Plaque is a late-10th or early-11th century Irish gilt-bronze sculpture showing the Crucifixion of Jesus, with two attendant angels hovering above his arms to his immediate left and right. Below them are representations of the Roman soldiers Stephaton and Longinus driving spears into his chest.

The Niederdollendorf stone or gravestone is a carved Frankish stele from the 7th century CE, named for the town Niederdollendorf where it was found in 1901 in a Frankish graveyard. The stone is a notable both as an exemplary work of Frankish sculpture and as a possible early example of Germanic Christian material culture.

The Landelinus buckle or Ladoix-Serrigny buckle is a 7th-century Merovingian belt buckle uncovered in Ladoix-Serrigny, France. The belt buckle is a notable example of early Christian iconography in Merovingian Burgundy, conjectured to depict an apocalyptic Christ on horseback. The buckle bears a Latin inscription identifying its creator as Landelinus, conjecturally identified by one scholar with Saint Landelin.

The Hornhausen stones are a set of fragmentary, 7th-century carved stones found in the village of Hornhausen in Saxony-Anhalt, Germany. The carved stones feature interlaced animal figures, deer, riders and their steeds, and a Christian flag.

The Essen-Werden casket is a reliquary casket of St Liudger Church in Essen-Werden. The casket is supposed to have originally served as a container for a small part of the wood from the cross of Jesus, which St Liudger (742–809) had received from the Pope in Rome in 784.

![Art historian Victor H. Elbern [de] has compared the Moselkern stele to such early medieval crucifixion reliefs as the Carndonagh stone. Carndonagh Marigold Stone East Face 2019 08 26.jpg](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/6/6d/Carndonagh_Marigold_Stone_East_Face_2019_08_26.jpg/220px-Carndonagh_Marigold_Stone_East_Face_2019_08_26.jpg)