Related Research Articles

Wicca, also known as "The Craft", is a modern pagan, syncretic, earth-centered religion. Scholars of religion categorize it as both a new religious movement and as part of occultist Western esotericism. It was developed in England during the first half of the 20th century and was introduced to the public in 1954 by Gerald Gardner, a retired British civil servant. Wicca draws upon a diverse set of ancient pagan and 20th-century hermetic motifs for its theological structure and ritual practices.

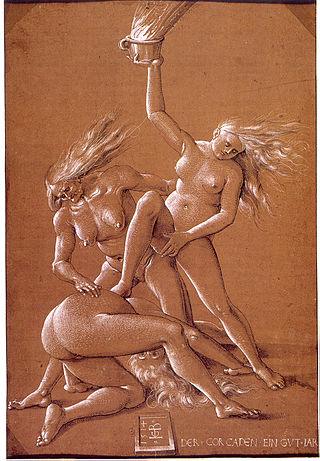

Witchcraft, as most commonly understood in both historical and present-day communities, is the use of alleged supernatural powers of magic. A witch is a practitioner of witchcraft. Traditionally, "witchcraft" means the use of magic or supernatural powers to inflict harm or misfortune on others, and this remains the most common and widespread meaning. According to Encyclopedia Britannica, "Witchcraft thus defined exists more in the imagination of contemporaries than in any objective reality. Yet this stereotype has a long history and has constituted for many cultures a viable explanation of evil in the world." The belief in witchcraft has been found in a great number of societies worldwide. Anthropologists have applied the English term "witchcraft" to similar beliefs in occult practices in many different cultures, and societies that have adopted the English language have often internalised the term.

Muthi is a traditional medicine practice in Southern Africa as far north as Lake Tanganyika.

The Witchcraft Acts were historically a succession of governing laws in England, Scotland, Wales, Ireland, and the British colonies on penalties for the practice, or—in later years—rather for pretending to practise witchcraft.

Traditional healers of Southern Africa are practitioners of traditional African medicine in Southern Africa. They fulfill different social and political roles in the community like divination, healing physical, emotional, and spiritual illnesses directing birth or death rituals, finding lost cattle, protecting warriors, counteracting witchcraft and narrating the history, cosmology, and concepts of their tradition.

A witch doctor was originally a type of healer who treated ailments believed to be caused by witchcraft. The term is now more commonly used to refer to healers, particularly in regions which use traditional healing rather than contemporary medicine.

Asian witchcraft encompasses various types of witchcraft practices across Asia. In ancient times, magic played a significant role in societies such as ancient Egypt and Babylonia, as evidenced by historical records. In the Middle East, references to magic can be found in the Torah and the Quran, where witchcraft is condemned due to its association with belief in magic, as it is within other Abrahamic religions.

Witchcraft in Latin America, known in Spanish as brujería, is a complex blend of indigenous, African, and European influences. Indigenous cultures had spiritual practices centered around nature and healing, while the arrival of Africans brought syncretic religions like Santería and Candomblé. European witchcraft beliefs merged with local traditions during colonization, contributing to the region's magical tapestry. Practices vary across countries, with accusations historically intertwined with social dynamics. A male practitioner is called a brujo, a female practitioner is a bruja.

European witchcraft is a multifaceted historical and cultural phenomenon that unfolded over centuries, leaving a mark on the continent's social, religious, and legal landscapes. The roots of European witchcraft trace back to classical antiquity when concepts of magic and religion were closely related, and society closely integrated magic and supernatural beliefs. Ancient Rome, then a pagan society, had laws against harmful magic. In the Middle Ages, accusations of heresy and devil worship grew more prevalent. By the early modern period, major witch hunts began to take place, partly fueled by religious tensions, societal anxieties, and economic upheaval. Witches were often viewed as dangerous sorceresses or sorcerers in a pact with the Devil, capable of causing harm through black magic. A feminist interpretation of the witch trials is that misogynist views of women led to the association of women and malevolent witchcraft.

The history of Wicca documents the rise of the Neopagan religion of Wicca and related witchcraft-based Neopagan religions. Wicca originated in the early 20th century, when it developed amongst secretive covens in England who were basing their religious beliefs and practices upon what they read of the historical witch-cult in the works of such writers as Margaret Murray. It also is based on the beliefs from the magic that Gerald Gardner saw when he was in India. It was subsequently founded in the 1950s by Gardner, who claimed to have been initiated into the Craft – as Wicca is often known – by the New Forest coven in 1939. Gardner's form of Wicca, the Gardnerian tradition, was spread by both him and his followers like the High Priestesses Doreen Valiente, Patricia Crowther and Eleanor Bone into other parts of the British Isles, and also into other, predominantly English-speaking, countries across the world. In the 1960s, new figures arose in Britain who popularized their own forms of the religion, including Robert Cochrane, Sybil Leek and Alex Sanders, and organizations began to be formed to propagate it, such as the Witchcraft Research Association. It was during this decade that the faith was transported to the United States, where it was further adapted into new traditions such as Feri, 1734 and Dianic Wicca in the ensuing decades, and where organizations such as the Covenant of the Goddess were formed.

Modern pagans are a religious minority in every country where they exist and have been subject to religious discrimination and/or religious persecution. The largest modern pagans communities are in North America and the United Kingdom, and the issue of discrimination receives most attention in those locations, but there are also reports from other countries.

Religion in South Africa is dominated by various branches of Christianity, which collectively represent around 78% of the country's total population.

Cunning folk, also known as folk healers or wise folk, were practitioners of folk medicine, helpful folk magic and divination in Europe from the Middle Ages until the 20th century. Their practices were known as the cunning craft. Their services also included thwarting witchcraft. Although some cunning folk were denounced as witches themselves, they made up a minority of those accused, and the common people generally made a distinction between the two. The name 'cunning folk' originally referred to folk-healers and magic-workers in Britain, but the name is now applied as an umbrella term for similar people in other parts of Europe.

The Witchcraft Act 1735 was an Act of the Parliament of the Kingdom of Great Britain in 1735 which made it a crime for a person to claim that any human being had magical powers or was guilty of practising witchcraft. With this, the law abolished the hunting and executions of witches in Great Britain. The maximum penalty set out by the Act was a year's imprisonment.

In Sub-Saharan Africa, "the practice of ritual killing and human sacrifice continues to take place ... in contravention of the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights and other human rights instruments." In the 21st century, in Nigeria, Uganda, Swaziland, Liberia, Tanzania, Namibia, and Zimbabwe, as well as Mozambique, and Mali, such practices have gotten the report.

The Witchcraft Suppression Act 3 of 1957 is an act of the Parliament of South Africa that prohibits various activities related to witchcraft, witch smelling or witch-hunting. It is based on the Witchcraft Suppression Act 1895 of the Cape Colony, which was in turn based on the Witchcraft Act 1735 of Great Britain.

Neopaganism in South Africa is primarily represented by the traditions of Wicca, Neopagan witchcraft, Germanic neopaganism and Neo-Druidism. The movement is related to comparable trends in the United States and Western Europe and is mostly practiced by White South Africans of urban background; it is to be distinguished from folk healing and mythology in local Bantu culture.

South Africa is a secular state, with freedom of religion enshrined in the Constitution.

Witchcraft is deeply rooted in many African countries and communities in Sub-Saharan Africa. It has been specifically relevant to Ghana's culture, beliefs, and lifestyle. It continues to shape lives daily and with that it has promoted tradition, fear, violence, and spiritual beliefs. The perceptions on witchcraft change from region to region within Ghana, as well as in other countries in Africa. The commonality is that it is not something to take lightly, and the word spreads fast if there are rumors' surrounding civilians practicing it. The actions taken by local citizens and the government towards witchcraft and violence related to it have also varied within regions in Ghana. Traditional African religions have depicted the universe as a multitude of spirits that are able to be used for good or evil through religion.

In Africa, witchcraft refers to various beliefs and practices. These beliefs often play a significant role in shaping social dynamics and can influence how communities address challenges and seek spiritual assistance.

References

- 1 2 Leff, Damon (2 September 2007). "S.A. Witches Will Define Themselves, Thank You". witchvox.com. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ↑ Witchcraft Suppression Act 3 of 1957

- ↑ "A National Health Plan for South Africa". anc.org.za. 30 May 1994. Archived from the original on 24 October 2012. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ↑ "Traditional Health Practitioners Act 22 of 2007". Archived from the original on 16 November 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ↑ Shonisani, Tshifhiwa (13 May 2011). "Healers threaten poll boycott". South Africa: The Citizen. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ↑ "Notice of Nominations of Members of the Interim Traditional Health Practitioners Council of South Africa: Traditional Health Practitioners Act, 2007 (Act No. 22 of 2007)" (PDF). doh.gov.za. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 November 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ↑ Harnischfeger, Johannes (2001). "Witchcraft and the State in South Africa". africana.ru.

- ↑ Niehaus, Isak (2001). Witchcraft, power, and politics: exploring the occult in the South African lowveld. Cape Town: David Philip. ISBN 9780745315638.

- ↑ Ashforth, Adam (2005). Witchcraft, Violence, and Democracy in South Africa. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226029733.

- ↑ "Religious discrimination in the new South Africa?". vuya.net. 24 July 2006. Archived from the original on 30 November 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ↑ "Truth and Reconciliation Commission Amnesty Hearing, Thohoyandou 12 July 1999". justice.gov.za. 12 July 1999. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ↑ Commission on Gender Equality (September 1998). "The Thohoyandou Declaration on Ending Witchcraft Violence". vuya.net. Archived from the original on 16 September 2007. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- 1 2 Department of Local Government and Housing, Mpumalanga Provincial Government (24 June 2008). "Mpumalanga province suspends the drafting of the provincial Witchcraft Suppression Bill of 2007". info.gov.za. Archived from the original on 4 July 2008. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ↑ Mpumalanga Provincial Government (31 May 2007). "Mashego-Dlamini: Mpumalanga Local Government and Housing Prov Budget Vote, 2007/08". polity.org.za. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- 1 2 Hlatshwayo, Riot (18 July 2007). "Healers, pagans oppose new witchcraft bill". The Sowetan. Retrieved 15 October 2012. "The Traditional Health Organisation (THO) and the South African Pagan Council (SAPC) opposed the bill. About 50 THO members, led by its national president, Nhlavana Maseko, met the Local Government and Housing Department."

- 1 2 "Bewitched or de-witched?". Mail & Guardian. 20 July 2007. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ↑ Flanagan, Louise (20 July 2007). "Witches need protection, says Sapra". South Africa: Independent Online. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ↑ Walker, Kylie (29 July 2007). "Western witches set out to defeat new law". South Africa: Independent Online. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ↑ "Sapra Appeal for legislative reform". vuya.net. 10 July 2007. Archived from the original on 20 December 2012. Retrieved 17 October 2012.

- ↑ Department of Justice and Constitutional Development. "Current Investigations: Progress Report; Project 135: Review of witchcraft legislation". justice.gov.za. Retrieved 15 October 2012.

- ↑ "South African Law Reform Commission Thirty Eighth Annual Report 2010/2011" (PDF). justice.gov.za. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ↑ "Review of Witchcraft Suppression Act (Act 3 of 1957)". paganrightsalliance.org. 6 March 2012. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- ↑ Petrus, Theodore (2009). An Anthropological Study of Witchcraft-related Crime in the Eastern Cape and its Implications for Law Enforcement Policy and Practice (PDF) (PhD thesis). Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University.

- ↑ De Lange, Ilse (6 July 2012). "Witchcraft education needed; South Africa not only needs new legislation to combat witchcraft-related crime, including muti murders, but also serious education campaigns and initiatives, particularly in rural communities". South Africa: The Citizen. Archived from the original on 21 May 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2012.