Muhi al-Din Muhammad, commonly known as Aurangzeb and by his regnal title Alamgir I, was the sixth emperor of the Mughal Empire, ruling from July 1658 until his death in 1707. Under his emperorship, the Mughals reached their greatest extent with their territory spanning nearly the entirety of the Indian subcontinent.

Mirza Nur-ud-Din Muhammad Salim, known by his imperial name Jahangir, was the fourth Mughal Emperor, who ruled from 1605 until his death in 1627. He was the third and only surviving son of Akbar and his chief empress, Mariam-uz-Zamani, born to them in the year 1569. He was named after the Indian Sufi saint, Salim Chishti.

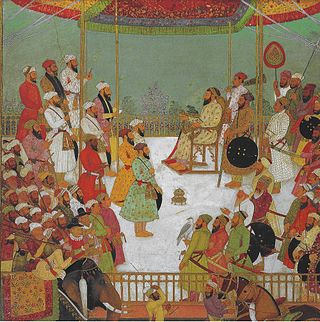

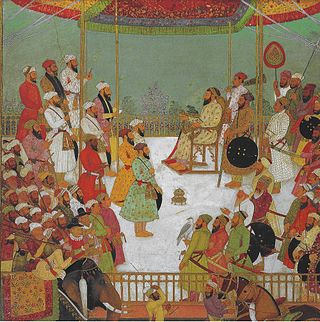

Mirza Shahab-ud-Din Baig Muhammad Khan Khurram, also known as Shah Jahan I, was the fifth Muslim emperor of the Mughal Empire, reigning from January 1628 until July 1658. Under his emperorship, the Mughals reached the peak of their architectural achievements and cultural glory.

Mumtaz Mahal, born Arjumand Banu Begum was the empress consort of Mughal Empire from 19 January 1628 to 17 June 1631 as the chief consort of the fifth Mughal emperor, Shah Jahan. The Taj Mahal in Agra, often cited as one of the Wonders of the World, was commissioned by her husband to act as her tomb.

Jahanara Begum was a Mughal princess and later the Padshah Begum of the Mughal Empire from 1631 to 1658 and again from 1668 until her death. She was the second and the eldest surviving child of Emperor Shah Jahan and Mumtaz Mahal.

Nur Jahan, born Mehr-un-Nissa was the twentieth wife and chief consort of the Mughal emperor Jahangir.

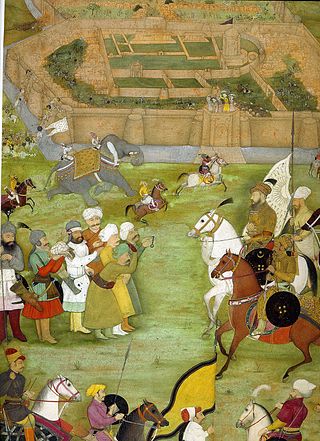

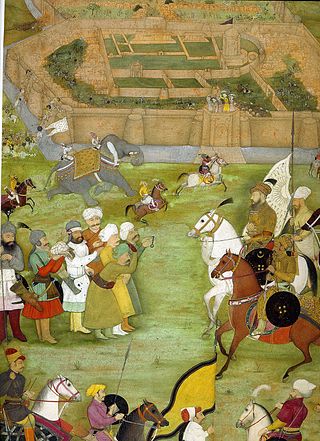

The Agra Fort is a historical fort in the city of Agra, and also known as Agra's Red Fort. Mughal emperor Humayun was crowned at this fort. It was later renovated by the Mughal emperor Akbar from 1565 and the present-day structure was completed in 1573. It served as the main residence of the rulers of the Mughal dynasty until 1638, when the capital was shifted from Agra to Delhi. It was also known as the "Lal-Qila" or "Qila-i-Akbari". Before capture by the British, the last Indian rulers to have occupied it were the Marathas. In 1983, the Agra fort was inscribed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site because of its importance during the Mughal Dynasty. It is about 2.5 kilometers (1.6 mi) northwest of its more famous sister monument, the Taj Mahal. The fort can be more accurately described as a walled city. It was later renovated by Shah Jahan.

Mughal architecture is the type of Indo-Islamic architecture developed by the Mughals in the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries throughout the ever-changing extent of their empire in the Indian subcontinent. It developed from the architectural styles of earlier Muslim dynasties in India and from Iranian and Central Asian architectural traditions, particularly Timurid architecture. It also further incorporated and syncretized influences from wider Indian architecture, especially during the reign of Akbar. Mughal buildings have a uniform pattern of structure and character, including large bulbous domes, slender minarets at the corners, massive halls, large vaulted gateways, and delicate ornamentation; examples of the style can be found in modern-day Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India and Pakistan.

Mirza Ghiyas Beg, also known by his title of I'timad-ud-Daulah, was an important Persian official in the Mughal empire, whose children served as wives, mothers, and generals of the Mughal emperors.

Salaf-ud-Din Muhammad Shahryar, better known as Shahryar Mirza, was the fifth and youngest son of the Mughal emperor Jahangir. At the end of Jahangir's life and after his death, Shahryar made an attempt to become emperor, planning, supported and conspiracy by his one in influence and powerful stepmother Nur Jahan, who was also his mother-in-law. The succession was contested, though Shahryar exercised power, based in Lahore, from 7 November 1627 to 19 January 1628, but like his father, he allowed Nur Jahan to run the affairs and consolidate his reign, but she did not succeed, and he was defeated and was killed at the orders of his brother Khurram, better known as Shah Jahan once he took the throne. Shahryar would have been the fifth Mughal Emperor, but is usually not counted in the list of Mughal Emperors.

The Hazratbal Shrine, popularly called Dargah Sharif, is a Muslim shrine located in Hazratbal locality of Srinagar in Jammu and Kashmir, India. It contains a relic, Moi-e-Muqqadas, which is widely believed to be the hair of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. It is situated on the northern bank of the Dal Lake in Srinagar, and is considered to be Kashmir's holiest Muslim shrine.

Abu'l-Hasan entitled by the Mughal emperor Jahangir as Asaf Khan, was the Grand Vizier of the fifth Mughal emperor Shah Jahan. He previously served as the vakil of Jahangir. Asaf Khan is perhaps best known for being the father of Arjumand Banu Begum, the chief consort of Shah Jahan and the older brother of Empress Nur Jahan, the chief consort of Jahangir.

Rafi-ul-Qadr, better known by his title, Mirza Rafi' ush-Shan Bahadur, was the third son of the Mughal emperor Bahadur Shah I.

Parviz Mirza was the second son of Mughal emperor Jahangir from his wife, Sahib Jamal. His daughter, Nadira Banu Begum, later became the wife of Dara Shikoh.

The Tomb of Nur Jahan is a 17th-century mausoleum in Lahore, Pakistan, that was built for the Mughal empress Nur Jahan. The tomb's marble was plundered during the Sikh era in 18th century for use at the Golden Temple in Amritsar. The red sandstone mausoleum, along with the nearby tomb of Jahangir, tomb of Asif Khan, and Akbari Sarai, forms part of an ensemble of Mughal monuments in Lahore's Shahdara Bagh.

Persian Inscriptions on Indian Monuments is a book written in Persian by Dr Ali Asghar Hekmat E Shirazi and published in 1956 and 1958 and 2013. New edition contains the Persian texts of more than 200 epigraphical inscriptions found on historical monuments in India, many of which are currently listed as national heritage sites or registered as UNESCO world heritage, published in Persian; an English edition is also being printed.

Parhez Banu Begum was a Mughal princess, the first child and eldest daughter of Mughal emperor Shah Jahan from his first wife, Qandahari Begum. She was also the older half-sister of her father's successor, the sixth Mughal emperor Aurangzeb.

The foreign relations of the Mughal Empire were characterized by competition with the Persian Empire to the west, the Marathas and others to the south, and the British to the east. Steps were taken by successive Mughal rulers to secure the western frontiers of India. The Khyber Pass along the Kabul- Qandhar route was the natural defence for India, and their foreign policy revolved around securing these outposts, as also balancing the rise of powerful empires in the region. During the break up of the Timurid Empire in the 15th century, the Ottomans in Turkey, the Safavids in Persia and the Uzbegs in central Asia emerged as the new contenders of power. While the Safavids were Shia by faith, Ottomans along with Uzbegs were Sunni. The Mughals were also Sunni and Uzbegs were their natural enemies, who caused Babur and other Timurid princes to leave Khurasan and Samarqand. The powerful Uzbegs who held sway over central India sought an alliance of Sunni powers to defeat the Shia ruled Persia, but Mughals were too broadminded to be driven away by the sectarian conflicts. The Mughal rulers, especially Akbar, were keen to develop strong ties with Persia in order to balance the warring Uzbegs. Thus, the foreign policy of Mughals was centred around strengthening the ties with Persia, while maintaining the balance of power in the region by keeping a check on the evolution of a united Uzbeg empire.

Mughal karkhanas were the manufacturing houses and workshops for craftsmen, established by the Mughals in their empire. Karkhana is a Hindustani language word that means factory. These karkhanas were small manufacturing units for various arts and crafts as well as for the emperor's household and military needs. karkhanas were named and classified based on the nature of the job. For example, 'Rangkhana' and 'Chhapakhana' were for textile dyeing and printing work. The term 'tushak-khana' was used to describe workshops that made shawls and embellished them with embroidery or needlework. Imperial or Royal Karkhanas were for luxury goods and weapons. The karkhanas were the place for various production activities and also for the exploration of new techniques and innovations. Some operations such as weaving, embroidery work, and brocade work were often done under one roof, resembling an integrated assembly line.

Sa'adullah Khan also spelled Sadullah Khan was a noble of the Mughal Empire who served as the last grand vizier of Emperor Shah Jahan, in the period 1645-1656. He was considered among the four most powerful nobles of the empire during Shah Jahan's time.