Background

In 1877, nearly 1,000 Northern Cheyenne surrendered to the U.S. army at Fort Robinson, Nebraska. The U.S. government sent them south with a military escort to the Cheyenne and Arapaho Indian Reservation in Indian Territory. During their journey south, the Cheyenne stopped to rest for a week in Dodge City, Kansas and became acquainted with many residents, notably lawman Bat Masterson. Conditions on the reservation in Oklahoma were difficult and in September 1878, 353 Cheyenne men, women, and children fled the reservation with the objective of returning to their former homeland on the northern Great Plains. They defeated the U.S. Army and civilian volunteers in several skirmishes. After the Battle of Punished Woman's Fork, the Cheyenne needed horses and provisions and raided in the Sappa Creek valley of northern Kansas. Despite the orders of their leaders to avoid killing non-combatants, Cheyenne warriors killed about 40 civilians and raped nine women. [1] [2]

After a flight northward of 900 km (560 mi) from Oklahoma, one hundred and fifty of the Cheyenne surrendered at Fort Robinson in October 1878. Imprisoned and ordered to return to Oklahoma, in January 1879 the Cheyenne escaped Fort Robinson. Many were killed or recaptured in the Fort Robinson breakout. Seven surviving men were arrested for the murders in Kansas. They and their families, a total of 21 persons, were sent to Fort Leavenworth. Kansas Governor George T. Anthony demanded that the seven be tried in a civilian court and Bat Masterson escorted the Cheyenne by rail from Fort Leavenworth to Dodge City for the trial, arriving there on 17 February 1879. The journey was widely publicized with crowds at every railroad station to see the Cheyenne. The crowds were both curious and hostile. Several Cheyenne were injured in the melees. The women and children were sent onward to Oklahoma. The Cheyenne had "sympathizers in the East and opponents in the West." [3]

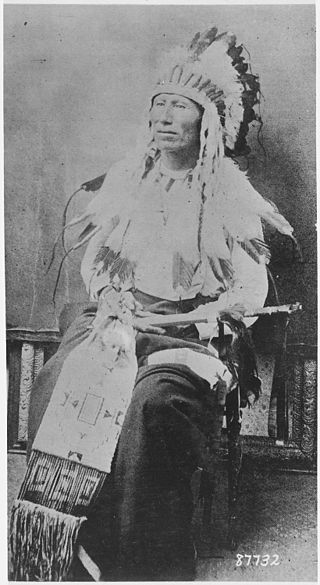

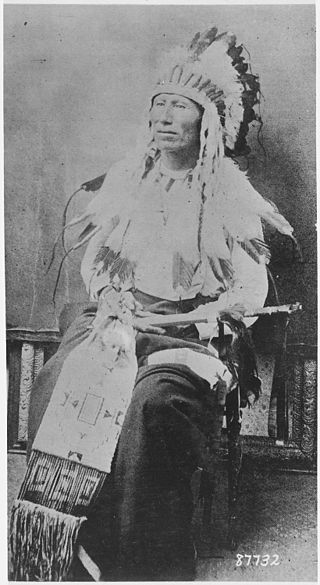

The seven Cheyenne were Old Crow, Wild Hog, Strong Left Hand, Porcupine, Tangle Hair, Noisy Walker, and Blacksmith. Old Crow and Wild Hog were Cheyenne leaders. Some of the others were Dog Soldiers, the most resistant of Cheyenne factions to white settlement on Cheyenne lands. [4] The seven were among the few Cheyenne men who survived the Fort Robinson breakout. Several of them had been seriously wounded, one had to be transported by wheelbarrow, and all were in poor health and believed to be suicidal. They anticipated they would be executed or lynched.

The trial

The imprisonment and trial of the seven Cheyenne illustrates both the animosity and the fascination of white Americans with Indians. The Cheyenne were shackled and put in the Dodge City jail in the damp basement of the county courthouse. They remained there five months. Many people, including journalists from prominent publications in the eastern United States, visited them in jail and gave them cigars in exchange for interviews. Sheriff Masterson provided food and medical care, and later in their incarceration the Cheyenne were allowed to bathe in the nearby Arkansas River and stay outside in the jail yard rather than the basement. A lawyer, J.G. Mohler, represented them and claimed that the state of Kansas had no jurisdiction over them. Mohler summoned many witnesses on behalf of the Cheyenne, and the prosecution had difficulty finding eye-witnesses to the killings. The seven Cheyenne proclaimed their innocence.

The Cheyenne were visited in Dodge City by the Indian agent, John DeBras Miles, who knew some of them. Miles secured the release of Old Crow, who had formerly worked with the U.S. Army as a scout, and sent him back to Indian Territory to work on the reservation. The remaining six prisoners were sent to Lawrence, Kansas because the trial there would be more impartial than in frontier Dodge City. They arrived in Lawrence on 25 June 1879 and became local celebrities. Wild Hog proved adept in giving a positive image of the Cheyenne to journalists. The Cheyenne attended a circus and participated in a rodeo, enacting a mock battle on horseback with local cowboys. Several prominent Kansans offered to testify on their behalf. Poet Walt Whitman visited them in jail. A committee of the United States Senate interviewed them on 12 August and Wild Hog presented his case of mistreatment of the Cheyenne while at the reservation in Indian Territory. Wild Hog's wife and daughters were allowed to visit him in jail and he gave the Mayor of Lawrence a collection of his wife's beadwork which found its way to the University of Kansas.

On 13 October 1879, the prosecuting attorney failed to appear in court and the presiding judge dismissed all charges against the Cheyenne. They were still considered prisoners of war, and were taken to the Cheyenne reservation in Indian Territory. Four years later most of them received permission to go to their northern homeland and reside on the newly created Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation.

The Arapaho are a Native American people historically living on the plains of Colorado and Wyoming. They were close allies of the Cheyenne tribe and loosely aligned with the Lakota and Dakota.

The Cheyenne are an Indigenous people of the Great Plains. Their Cheyenne language belongs to the Algonquian language family. Today, the Cheyenne people are split into two federally recognized nations: the Southern Cheyenne, who are enrolled in the Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes in Oklahoma, and the Northern Cheyenne, who are enrolled in the Northern Cheyenne Tribe of the Northern Cheyenne Indian Reservation in Montana.

Kiowa or CáuigúIPA:[kɔ́j-gʷú]) people are a Native American tribe and an Indigenous people of the Great Plains of the United States. They migrated southward from western Montana into the Rocky Mountains in Colorado in the 17th and 18th centuries, and eventually into the Southern Plains by the early 19th century. In 1867, the Kiowa were moved to a reservation in southwestern Oklahoma.

The Dog Soldiers or Dog Men are historically one of six Cheyenne military societies. Beginning in the late 1830s, this society evolved into a separate, militaristic band that played a dominant role in Cheyenne resistance to the westward expansion of the United States in the area of present-day Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado, and Wyoming, where the Cheyenne had settled in the early nineteenth century.

Little Wolf was a Northern Só'taeo'o Chief and Sweet Medicine Chief of the Northern Cheyenne. He was known as a great military tactician and led a dramatic escape from confinement in Oklahoma back to the Northern Cheyenne homeland in 1878, known as the Northern Cheyenne Exodus.

The Ponca people are a nation primarily located in the Great Plains of North America that share a common Ponca culture, history, and language, identified with two Indigenous nations: the Ponca Tribe of Indians of Oklahoma or the Ponca Tribe of Nebraska.

The Sioux Wars were a series of conflicts between the United States and various subgroups of the Sioux people which occurred in the later half of the 19th century. The earliest conflict came in 1854 when a fight broke out at Fort Laramie in Wyoming, when Sioux warriors killed 31 American soldiers in the Grattan Massacre, and the final came in 1890 during the Ghost Dance War.

Morning Star (1810–1883) was a great chief of the Northern Cheyenne people and headchief of the Notameohmésêhese band on the northern Great Plains during the 19th century. He was noted for his active resistance to westward expansion and the United States federal government. It is due to the courage and determination of Morning Star and other leaders that the Northern Cheyenne still possess a homeland in their traditional country in present-day Montana.

White Buffalo was a chief of the Northern Cheyenne. He was born in Montana Territory to the Northern Cheyenne tribe but was forced with most of his tribe to remove to Indian Territory. He lived most of his life on the Cheyenne and Arapaho Reservation in Indian Territory and then Oklahoma. He graduated in 1884 as one of the early attendees of Carlisle Indian Industrial School, in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, one of 249 students from his tribe to attend that school over the years of its operation.

The Great Sioux War of 1876, also known as the Black Hills War, was a series of battles and negotiations that occurred in 1876 and 1877 in an alliance of Lakota Sioux and Northern Cheyenne against the United States. The cause of the war was the desire of the US government to obtain ownership of the Black Hills. Gold had been discovered in the Black Hills, settlers began to encroach onto Native American lands, and the Sioux and the Cheyenne refused to cede ownership. Traditionally, American military and historians place the Lakota at the center of the story, especially because of their numbers, but some Native Americans believe the Cheyenne were the primary target of the American campaign.

Ledger art is narrative drawing or painting on paper or cloth, predominantly practiced by Plains Indian, but also from the Plateau and Great Basin. Ledger art flourished primarily from the 1860s to the 1920s. A revival of ledger art began in the 1960s and 1970s. The term comes from the accounting ledger books that were a common source of paper for Plains Indians during the late 19th century.

The Cheyenne and Arapaho Tribes are a united, federally recognized tribe of Southern Arapaho and Southern Cheyenne people in western Oklahoma.

The Northern Cheyenne Exodus, also known as Dull Knife's Raid, the Cheyenne War, or the Cheyenne Campaign, was the attempt of the Northern Cheyenne to return to the north, after being placed on the Southern Cheyenne reservation in the Indian Territory, and the United States Army operations to stop them. The period lasted from 1878 to 1879.

The Fort Robinson breakout or Fort Robinson massacre was the attempted escape of Cheyenne captives from the U.S. army during the winter of 1878-1879 at Fort Robinson in northwestern Nebraska. In 1877, the Cheyenne had been forced to relocate from their homelands on the northern Great Plains south to the Darlington Agency on the Southern Cheyenne Reservation in Indian Territory (Oklahoma). In September 1878, in what is called the Northern Cheyenne Exodus, 353 Northern Cheyenne fled north because of poor conditions on the reservation. In Nebraska, the U.S. Army captured 149 of the Cheyenne, including 46 warriors, and escorted them to Fort Robinson.

Howling Wolf was a Southern Cheyenne warrior who was a member of Black Kettle's band and was present at the Sand Creek Massacre in Colorado. After being imprisoned in the Fort Marion in Saint Augustine, Florida in 1875, Howling Wolf became a proficient artist in a style known as Ledger art for the accounting ledger books in which the drawings were done.

Little Shield was a chieftain of the Northern Cheyenne from 1865–1879. He is known for creating a collection of ledger drawings accounting the Indian wars along the North Platte river. Little Shield also fought in the Battle of Little Bighorn, leading the Dog Soldiers.

The Battle of Punished Woman's Fork, also called Battle Canyon, was the last battle between Native Americans (Indians) and the United States Army in the state of Kansas. In the Northern Cheyenne Exodus, 353 Cheyenne, including women and children, fled their reservation in Oklahoma in an attempt to return to their homeland on the northern Great Plains. In Kansas, they fought soldiers of the U.S. Army at Punished Woman's Fork, killing the army commander. After the battle the Cheyenne continued northward. Some were successful in reaching their relatives in Montana. Others were captured or killed near Camp Robinson, Nebraska.

Porcupine was a Cheyenne chief and medicine man. He is best known for bringing the Ghost Dance religion to the Cheyenne. Raised with the Sioux of a Cheyenne mother, he married a Cheyenne himself and became a warrior in the Cheyenne Dog Soldiers.

The Battle of Turkey Springs was the last battle between Native Americans (Indians) and the United States Army in the state of Oklahoma. In the Northern Cheyenne Exodus, 353 Cheyenne Indians, fleeing their reservation in Oklahoma in an attempt to return to their homeland in the northern Great Plains, fought a unit of the United States Army, killing three soldiers. After the battle the Cheyenne continued northward skirmishing with the army along the way. Some were successful in reaching their relatives in Montana. Others were captured or killed near Camp Robinson, Nebraska.

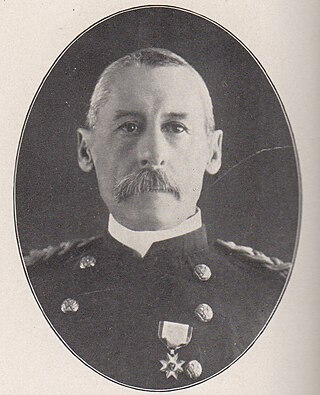

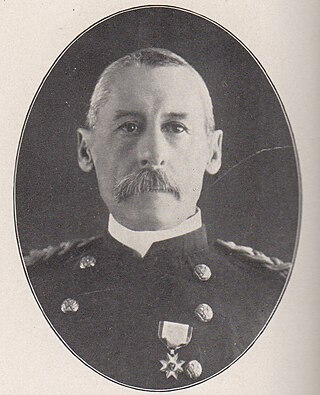

Henry Walton Wessells Jr. (1846-1929) was an American brigadier general of the American Indian Wars, the Spanish–American War and the Philippine–American War. He was known for being the son of Brigadier General Henry W. Wessells, his participation in the Fort Robinson breakout and his command of the 3rd Cavalry Regiment during the Battle of San Juan Hill.