The Indian removal was the United States government's policy of ethnic cleansing through the forced displacement of self-governing tribes of American Indians from their ancestral homelands in the eastern United States to lands west of the Mississippi River—specifically, to a designated Indian Territory, which many scholars have labeled a genocide. The Indian Removal Act of 1830, the key law which authorized the removal of Native tribes, was signed into law by United States president Andrew Jackson on May 28, 1830. Although Jackson took a hard line on Indian removal, the law was primarily enforced during the Martin Van Buren administration. After the enactment of the Act, approximately 60,000 members of the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Seminole, Chickasaw, and Choctaw nations were forcibly removed from their ancestral homelands, with thousands dying during the Trail of Tears.

Indian Territory and the Indian Territories are terms that generally described an evolving land area set aside by the United States government for the relocation of Native Americans who held original Indian title to their land as an independent nation-state. The concept of an Indian territory was an outcome of the U.S. federal government's 18th- and 19th-century policy of Indian removal. After the American Civil War (1861–1865), the policy of the U.S. government was one of assimilation.

The Trail of Tears was the forced displacement of approximately 60,000 people of the "Five Civilized Tribes" between 1830 and 1850, and the additional thousands of Native Americans and their enslaved African Americans within that were ethnically cleansed by the United States government.

The Chickasaw are an Indigenous people of the Southeastern Woodlands, United States. Their traditional territory was in northern Mississippi, northwestern and northern Alabama, western Tennessee and southwestern Kentucky. Their language is classified as a member of the Muskogean language family. In the present day, they are organized as the federally recognized Chickasaw Nation.

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by the United States government in the early federal period of the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast: the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee (Creek), and Seminoles. White Americans classified them as "civilized" because they had adopted attributes of the Anglo-American culture.

The Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek was a treaty which was signed on September 27, 1830, and proclaimed on February 24, 1831, between the Choctaw American Indian tribe and the United States Government. This treaty was the first removal treaty which was carried into effect under the Indian Removal Act. The treaty ceded about 11 million acres (45,000 km2) of the Choctaw Nation in what is now Mississippi in exchange for about 15 million acres (61,000 km2) in the Indian territory, now the state of Oklahoma. The principal Choctaw negotiators were Chief Greenwood LeFlore, Mosholatubbee, and Nittucachee; the U.S. negotiators were Colonel John Coffee and Secretary of War John Eaton.

The Fort Smith Council, also known as the Indian Council, was a series of meetings held at Fort Smith, Arkansas from September 8–21, 1865, that were organized by the United States Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Dennis N. Cooley, for Indian tribes east of the Rockies.

John McKee was an American politician active in the Southeastern United States. He served as agent to the Cherokees and Choctaws, and was the first Representative of Alabama's 2nd District from 1823 to 1829. He was also commissioned by President James Madison in 1811 to help wrest East and West Florida from Spanish control.

The Treaty of Doak's Stand was signed on October 18, 1820 between the United States and the Choctaw Indian tribe. The Treaty of Doak's Stand was the seventh of nine major treaties that were ratified from the period from 1786 through 1866 between the United States government and the Choctaw nation during a time of rapid westward expansion of white settlers. Based on the terms of the accord, the Choctaw were forced to give up approximately 5 million acres or roughly one-third of their remaining Choctaw homeland in the east in exchange for 13 million westward acres in the Canadian Kiamichi, Arkansas, and Red River watersheds. The Choctaw reluctantly signed the agreement in an effort to maintain peace as they were threatened by the US commissioners that if they did not agree to move west, they would perish.

William Clyde Thompson was a Texas Choctaw-Chickasaw leader of the Mount Tabor Indian Community in Texas and an officer of the Confederate States of America during the Civil War. After moving north to the Chickasaw Nation in 1889, he led an effort to gain enrollment of his family and other Texas Choctaws as Citizens by blood of the Choctaw Nation in Indian Territory. This was at the time of enrollment for the Final Roll of the Five Civilized Tribes, also known as the Dawes Rolls, which established citizenship in order for the nations to be broken up for white settlement and to allot communal tribal lands to individual Indians. The Choctaw Advisory Board opposed inclusion of the Texas Choctaw as well as the Jena Choctaws in Louisiana, as they had both lived primarily outside of the Choctaw Nation. Thompson's case eventually went to the United States Supreme Court to be decided where he and about 70 other Texas Choctaws who had relocated to Indian Territory ultimately had their status restored as Citizens by Blood in the Choctaw Nation.

The Treaty with Choctaws and Chickasaws was a treaty signed on July 12, 1861 between the Choctaw and Chickasaw and the Confederate States.

The Yowani were a historical group of Choctaw people who lived in Texas. Yowani was also the name of a preremoval Choctaw village.

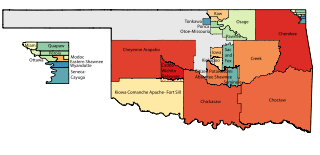

Oklahoma Tribal Statistical Area is a statistical entity identified and delineated by federally recognized American Indian tribes in Oklahoma as part of the U.S. Census Bureau's 2010 Census and ongoing American Community Survey. Many of these areas are also designated Tribal Jurisdictional Areas, areas within which tribes will provide government services and assert other forms of government authority. They differ from standard reservations, such as the Osage Nation of Oklahoma, in that allotment was broken up and as a consequence their residents are a mix of native and non-native people, with only tribal members subject to the tribal government. At least five of these areas, those of the so-called five civilized tribes of Cherokee, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Creek and Seminole, which cover 43% of the area of the state, are recognized as reservations by federal treaty, and thus not subject to state law or jurisdiction for tribal members.

The Cherokee Commission, was a three-person bi-partisan body created by 23rd President Benjamin Harrison, to operate under the direction of the United States Secretary of the Interior, of the President's Cabinet, as empowered by Section 14 of the Indian Appropriations Act of March 2, 1889, passed by the United States Congress and signed by President Harrison. Section 15 of the same Act empowered the President of the United States to open land for settlement. The Commission's purpose was to legally acquire land already occupied by the Cherokee Nation and other tribes in the new Oklahoma Territory for non-indigenous homestead acreage.

An Organic Act is a generic name for a statute used by the United States Congress to describe a territory, in anticipation of being admitted to the Union as a state. Because of Oklahoma's unique history an explanation of the Oklahoma Organic Act needs a historic perspective. In general, the Oklahoma Organic Act may be viewed as one of a series of legislative acts, from the time of Reconstruction, enacted by Congress in preparation for the creation of a united State of Oklahoma. The Organic Act created Oklahoma Territory, and Indian Territory that were Organized incorporated territories of the United States out of the old "unorganized" Indian Territory. The Oklahoma Organic Act was one of several acts whose intent was the assimilation of the tribes in Oklahoma and Indian Territories through the elimination of tribes' communal ownership of property.

On the eve of the American Civil War in 1861, a significant number of Indigenous peoples of the Americas had been relocated from the Southeastern United States to Indian Territory, west of the Mississippi. The inhabitants of the eastern part of the Indian Territory, the Five Civilized Tribes, were suzerain nations with established tribal governments, well established cultures, and legal systems that allowed for slavery. Before European Contact these tribes were generally matriarchial societies, with agriculture being the primary economic pursuit. The bulk of the tribes lived in towns with planned streets, residential and public areas. The people were ruled by complex hereditary chiefdoms of varying size and complexity with high levels of military organization.

The Treaty of Pontotoc Creek was a treaty signed on October 20, 1832 by representatives of the United States and the Chiefs of the Chickasaw Nation assembled at the National Council House on Pontotoc Creek in Pontotoc, Mississippi. The treaty ceded the 6,283,804 million acres of the remaining Chickasaw homeland in Mississippi in return for Chickasaw relocation on an equal amount of land west of the Mississippi River.

The ownership of enslaved people by indigenous peoples of the Americas extended throughout the colonial period up to the abolition of slavery. Indigenous people enslaved Amerindians, Africans, and—occasionally—Europeans.

A Superintendent of Indian Affairs was a regional administrator who supervised groups of Indian Agents who worked directly with individual tribes. It was the responsibility of the Superintendent to see that the Indian Agents complied with official government policy. The records for Superintendencies exist in the National Archives and in the Bureau of Indian Affairs; additionally, copies may be available in other official record storage or research facilities.