The original decision

The Court had issued its original opinion, written by Chief Judge Douglas H. Ginsburg and joined by Judges Judith Rogers and Janice Rogers Brown, on August 22, 2006. The opinion had struck down 26 U.S.C. § 104(a)(2) to the extent that the statute purported to categorize compensatory damages for emotional distress and loss of reputation as being includible in gross income for Federal income tax purposes. [1]

Marrita Murphy was represented by David K. Colapinto of the law firm Kohn, Kohn & Colapinto, who also handled her appeal before the D.C. Circuit. Murphy had sued to recover income taxes that she paid on the compensatory damages for emotional distress and loss of reputation that she was awarded in an action against her former employer under whistle-blower statutes for reporting environmental hazards on her former employer's property to state authorities. Murphy had claimed both physical and emotional-distress damages as a result of her former employer's retaliation and mistreatment.

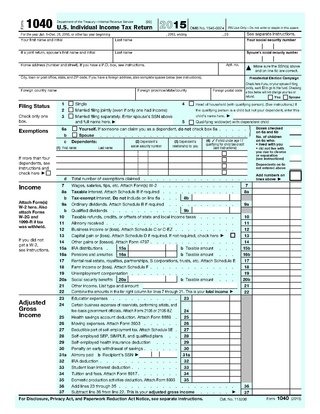

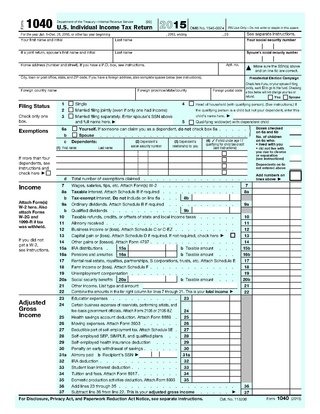

In a prior administrative proceeding, Murphy had been awarded compensatory damages of $70,000, of which $45,000 was for "emotional distress or mental anguish" and $25,000 was for "injury to professional reputation." Murphy reported the $70,000 award as part of her "gross income" and paid $20,665 in Federal income taxes based upon the award.

Section 104(a)(2) of the Internal Revenue Code excludes, from gross income, amounts "received . . . on account of personal physical injuries." [4] The statute provides that for purposes of that exclusion, "emotional distress shall not be treated as a physical injury or physical sickness." [4] Based on that provision, Murphy sought a refund of the full amount of tax, arguing that the award should be exempt from taxation both because the award was "in fact" to compensate for "physical personal injuries" and because the award was not "income" within the meaning of the Sixteenth Amendment. [5]

Interpreting Section 104(a)(2), the D.C. Circuit first held in August 2006 that the damages at issue did not fall within the scope of the statute because the damages were not in fact to compensate for "personal physical injuries," and thus could not be excluded from gross income under that provision. [6]

The D.C. Circuit next analyzed whether Section 104(a)(2) is "constitutional," relying upon language from Commissioner v. Glenshaw Glass Co. [7] to the effect that, under the Sixteenth Amendment, Congress may "tax all gains" or "accessions to wealth." [8] Murphy argued that her award was neither a gain nor an accession to wealth because it compensated her for nonphysical injuries, and was thus effectively a restoration of "human capital." [8]

Recognizing that the Supreme Court has long held that a restoration of capital "[i]s not income," and thus is not taxable, and that personal injury recoveries have traditionally been considered "nontaxable on the theory that they roughly correspond to a return of capital," the D.C. Circuit accepted Murphy's argument in its August 2006 decision. [9] The D.C. Circuit reasoned that Murphy's award for emotional distress or loss of reputation is not taxable because her damages "were awarded to make Murphy emotionally and reputationally 'whole' and not to compensate her for lost wages or taxable earnings of any kind." [10] The D.C. Circuit also explained that a 1918 opinion of the Attorney General stating that proceeds from an accident insurance policy were not taxable income and a 1922 IRS ruling that damages based on loss of reputation were not taxable income, both issued relatively near the Sixteenth Amendment's ratification in 1913, support its ruling. [11] The D.C. Circuit thus concluded that "the framers of the Sixteenth Amendment would not have understood compensation for a personal injury – including a nonphysical injury – to be income." [12] Murphy's position was that her award constituted only monies that "made her whole" and, in effect, was a return of her "human capital."

Rehearing and decision

The parties presented oral arguments in a rehearing on April 23, 2007, [13]

On July 3, 2007, the Court ruled (1) that the taxpayer's compensation was received on account of a non-physical injury or sickness; (2) that gross income under section 61 of the Internal Revenue Code [14] does include compensatory damages for non-physical injuries, even if the award is not an "accession to wealth," (3) that the income tax imposed on an award for non-physical injuries is an indirect tax, regardless of whether the recovery is restoration of "human capital," and therefore the tax does not violate the constitutional requirement of Article I, section 9, that capitations or other direct taxes must be laid among the states only in proportion to the population; (4) that the income tax imposed on an award for non-physical injuries does not violate the constitutional requirement of Article I, section 8, that all duties, imposts and excises be uniform throughout the United States; (5) that under the doctrine of sovereign immunity, the Internal Revenue Service may not be sued in its own name. [3] The Court stated: "[a]lthough the 'Congress cannot make a thing income which is not so in fact,' [ . . . ] it can label a thing income and tax it, so long as it acts within its constitutional authority, which includes not only the Sixteenth Amendment but also Article I, Sections 8 and 9." [3] Citing Commissioner v. Banks, the court noted that "the power of the Congress to tax income 'extends broadly to all economic gains.'" [15] The court ruled that Ms. Murphy was not entitled to the tax refund she claimed, and that the personal injury award she received was "within the reach of the congressional power to tax under Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution"—even if the award was "not income within the meaning of the Sixteenth Amendment". [3]

The Sixteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution allows Congress to levy an income tax without apportioning it among the states on the basis of population. It was passed by Congress in 1909 in response to the 1895 Supreme Court case of Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co. The Sixteenth Amendment was ratified by the requisite number of states on February 3, 1913, and effectively overruled the Supreme Court's ruling in Pollock.

Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Company, 157 U.S. 429 (1895), affirmed on rehearing, 158 U.S. 601 (1895), was a landmark case of the Supreme Court of the United States. In a 5-to-4 decision, the Supreme Court struck down the income tax imposed by the Wilson–Gorman Tariff Act for being an unapportioned direct tax. The decision was superseded in 1913 by the Sixteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which allows Congress to levy income taxes without apportioning them among the states.

Brushaber v. Union Pacific Railroad Co., 240 U.S. 1 (1916), was a landmark United States Supreme Court case in which the Court upheld the validity of a tax statute called the Revenue Act of 1913, also known as the Tariff Act, Ch. 16, 38 Stat. 166, enacted pursuant to Article I, section 8, clause 1 of, and the Sixteenth Amendment to, the United States Constitution, allowing a federal income tax. The Sixteenth Amendment had been ratified earlier in 1913. The Revenue Act of 1913 imposed income taxes that were not apportioned among the states according to each state's population.

Hustler Magazine, Inc. v. Falwell, 485 U.S. 46 (1988), was a landmark decision of the United States Supreme Court ruling that the First and Fourteenth Amendments prohibit public figures from recovering damages for the tort of intentional infliction of emotional distress (IIED), if the emotional distress was caused by a caricature, parody, or satire of the public figure that a reasonable person would not have interpreted as factual.

Bob Jones University v. United States, 461 U.S. 574 (1983), was a decision by the United States Supreme Court holding that the religion clauses of the First Amendment did not prohibit the Internal Revenue Service from revoking the tax exempt status of a religious university whose practices are contrary to a compelling government public policy, such as eradicating racial discrimination.

Hylton v. United States, 3 U.S. 171 (1796), is an early United States Supreme Court case in which the Court held that a yearly tax on carriages did not violate the Article I, Section 2, Clause 3 and Article I, Section 9, Clause 4 requirements for the apportioning of direct taxes. The Court concluded that the carriage tax was not a direct tax, which would require apportionment among the states. The Court noted that a tax on land was an example of a direct tax that was contemplated by the Constitution.

The United States federal government and most state governments impose an income tax. They are determined by applying a tax rate, which may increase as income increases, to taxable income, which is the total income less allowable deductions. Income is broadly defined. Individuals and corporations are directly taxable, and estates and trusts may be taxable on undistributed income. Partnerships are not taxed, but their partners are taxed on their shares of partnership income. Residents and citizens are taxed on worldwide income, while nonresidents are taxed only on income within the jurisdiction. Several types of credits reduce tax, and some types of credits may exceed tax before credits. An alternative tax applies at the federal and some state levels.

Commissioner v. Glenshaw Glass Co., 348 U.S. 426 (1955), was an important income tax case before the United States Supreme Court. The Court held as follows:

A tax protester, in the United States, is a person who denies that he or she owes a tax based on the belief that the Constitution, statutes, or regulations do not empower the government to impose, assess or collect the tax. The tax protester may have no dispute with how the government spends its revenue. This differentiates a tax protester from a tax resister, who seeks to avoid paying a tax because the tax is being used for purposes with which the resister takes issue.

The Law That Never Was: The Fraud of the 16th Amendment and Personal Income Tax is a 1985 book by William J. Benson and Martin J. "Red" Beckman which claims that the Sixteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, commonly known as the income tax amendment, was never properly ratified. In 2007, and again in 2009, Benson's contentions were ruled to be fraudulent.

Bob Jones University v. Simon, 416 U.S. 725 (1974), is a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States holding that Bob Jones University, which had its 501(c)(3) status revoked by the Internal Revenue Service for practicing "racially discriminatory admissions policies" towards African-Americans, could not sue for an injunction to prevent losing its tax-exempt status. The question of Bob Jones University's tax-exempt status was ultimately resolved in Bob Jones University v. United States, in which the court ruled that the First Amendment did not protect discriminatory organizations from losing tax-exempt status.

Tax protesters in the United States have advanced a number of arguments asserting that the assessment and collection of the federal income tax violates statutes enacted by the United States Congress and signed into law by the President. Such arguments generally claim that certain statutes fail to create a duty to pay taxes, that such statutes do not impose the income tax on wages or other types of income claimed by the tax protesters, or that provisions within a given statute exempt the tax protesters from a duty to pay.

We the People Foundation for Constitutional Education, Inc. also known as We the People Foundation is a non-profit education and research organization in Queensbury, New York with the declared mission "to protect and defend individual Rights as guaranteed by the Constitutions of the United States." It was founded by Robert L. Schulz. At the U.S. Department of Justice, he is known as a "high-profile tax protester". The Southern Poverty Law Center asserts that Schulz is the head of the leading organization in the tax protester movement. The organization formally served a petition for redress of grievances regarding income tax upon the United States government in November 2002. In July 2004, it filed a lawsuit in an unsuccessful attempt to force the government to address the petition. The organization has also served petitions relating to other issues since then.

The National Whistleblower Center (NWC) is a nonprofit, nonpartisan, tax exempt, educational and advocacy organization based in Washington, D.C. It was founded in 1988 by the lawyers Kohn, Kohn & Colapinto, LLP. As of March 2019, John Kostyack is the executive director. Since its founding, the center has worked on whistleblower cases relating to environmental protection, nuclear safety, government and corporate accountability, and wildlife crime.

The history of taxation in the United States begins with the colonial protest against British taxation policy in the 1760s, leading to the American Revolution. The independent nation collected taxes on imports ("tariffs"), whiskey, and on glass windows. States and localities collected poll taxes on voters and property taxes on land and commercial buildings. In addition, there were the state and federal excise taxes. State and federal inheritance taxes began after 1900, while the states began collecting sales taxes in the 1930s. The United States imposed income taxes briefly during the Civil War and the 1890s. In 1913, the 16th Amendment was ratified, however, the United States Constitution Article 1, Section 9 defines a direct tax. The Sixteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution did not create a new tax.

Tax protester Sixteenth Amendment arguments are assertions that the imposition of the U.S. federal income tax is illegal because the Sixteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which reads "The Congress shall have power to lay and collect taxes on incomes, from whatever source derived, without apportionment among the several States, and without regard to any census or enumeration", was never properly ratified, or that the amendment provides no power to tax income. Proper ratification of the Sixteenth Amendment is disputed by tax protesters who argue that the quoted text of the Amendment differed from the text proposed by Congress, or that Ohio was not a State during ratification, despite its admission to the Union on March 1st, 1803, more than a century prior. Sixteenth Amendment ratification arguments have been rejected in every court case where they have been raised and have been identified as legally frivolous.

Tax protesters in the United States advance a number of constitutional arguments asserting that the imposition, assessment and collection of the federal income tax violates the United States Constitution. These kinds of arguments, though related to, are distinguished from statutory and administrative arguments, which presuppose the constitutionality of the income tax, as well as from general conspiracy arguments, which are based upon the proposition that the three branches of the federal government are involved together in a deliberate, on-going campaign of deception for the purpose of defrauding individuals or entities of their wealth or profits. Although constitutional challenges to U.S. tax laws are frequently directed towards the validity and effect of the Sixteenth Amendment, assertions that the income tax violates various other provisions of the Constitution have been made as well.

A tax protester is someone who refuses to pay a tax claiming that the tax laws are unconstitutional or otherwise invalid. Tax protesters are different from tax resisters, who refuse to pay taxes as a protest against a government or its policies, or a moral opposition to taxation in general, not out of a belief that the tax law itself is invalid. The United States has a large and organized culture of people who espouse such theories. Tax protesters also exist in other countries.

Taxation of income in the United States has been practised since colonial times. Some southern states imposed their own taxes on income from property, both before and after Independence. The Constitution empowered the federal government to raise taxes at a uniform rate throughout the nation, and required that "direct taxes" be imposed only in proportion to the Census population of each state. Federal income tax was first introduced under the Revenue Act of 1861 to help pay for the Civil War. It was renewed in later years and reformed in 1894 in the form of the Wilson-Gorman tariff.

Tax protesters in the United States advance a number of administrative arguments asserting that the assessment and collection of the federal income tax violates regulations enacted by responsible agencies –primarily the Internal Revenue Service (IRS)– tasked with carrying out the statutes enacted by the United States Congress and signed into law by the President. Such arguments generally include claims that the administrative agency fails to create a duty to pay taxes, or that its operation conflicts with some other law, or that the agency is not authorized by statute to assess or collect income taxes, to seize assets to satisfy tax claims, or to penalize persons who fail to file a return or pay the tax.