Related Research Articles

Family Ties is an American television sitcom that aired on NBC for seven seasons, premiering on September 22, 1982, and concluding on May 14, 1989. The series, created by Gary David Goldberg, reflected the social shift in the United States from the cultural liberalism of the 1960s and 1970s to the conservatism of the 1980s. Because of this, Young Republican Alex P. Keaton develops generational strife with his ex-hippie parents, Steven and Elyse Keaton.

Harriet Jacobs was an African-American abolitionist and writer whose autobiography, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, published in 1861 under the pseudonym Linda Brent, is now considered an "American classic".

Maria Elisa Cristobal Anson-Rodrigo, better known as Boots Anson-Roa, is a Filipina actress, columnist, editor, and lecturer.

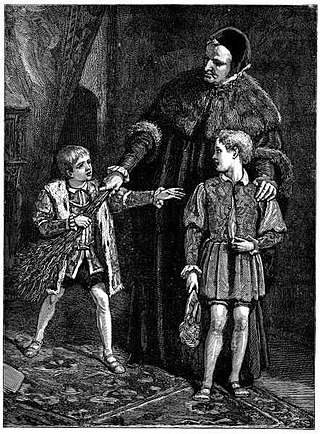

A whipping boy was a boy educated alongside a prince in early modern Europe, who supposedly received corporal punishment for the prince's transgressions in his presence. The prince was not punished himself because his royal status exceeded that of his tutor; seeing a friend punished would provide an equivalent motivation not to repeat the offence. An archaic proverb which captures a similar idea is "to beat a dog before a lion". Whipping was a common punishment administered by tutors at that time. There is little contemporary evidence for the existence of whipping boys, and evidence that some princes were indeed whipped by their tutors, although Nicholas Orme suggests that nobles might have been beaten less often than other pupils. Some historians regard whipping boys as entirely mythical; others suggest they applied only in the case of a boy king, protected by divine right, and not to mere princes.

Roots is a 1977 American television miniseries based on Alex Haley's 1976 novel Roots: The Saga of an American Family, set during and after the era of enslavement in the United States. The series first aired on ABC in January 1977 over eight consecutive nights.

Roots: The Saga of an American Family is a 1976 novel written by Alex Haley. It tells the story of Kunta Kinte, an 18th-century Mandinka, captured as an adolescent, sold into slavery in Africa, and transported to North America. It explores his life and those of his descendants in the United States, down to Haley. The novel was quickly adapted as a hugely popular television miniseries, Roots (1977). Together, the novel and series were a cultural sensation in the United States. The novel spent forty-six weeks on The New York Times Best Seller list, including twenty-two weeks at number one.

Loletha Elayne Falana or Loletha Elaine Falana, better known by her stage name Lola Falana, is an American singer, dancer, and actress. She was nominated for the Tony Award for Best Actress in a Musical in 1975 for her performance as Edna Mae Sheridan in Doctor Jazz.

Jodi Lynn Picoult is an American writer. Picoult has published 28 novels and short stories, and has also written several issues of Wonder Woman. Approximately 40 million copies of her books are in print worldwide and have been translated into 34 languages. In 2003, she was awarded the New England Bookseller Award for fiction.

Caramelo is a 2002 epic novel spanning a hundred years of Mexican history by American author Sandra Cisneros. It was inspired by her Mexican heritage and childhood in the barrio of Chicago, Illinois. The main character, Lala, is the only girl in a family of seven children and her family often travels between Chicago and Mexico City. Because Cisneros also has six brothers and her family moved frequently when she was a child, the novel is semi-autobiographical. The novel could also be called a Bildungsroman, as it focuses on Lala's development from childhood onward. It was shortlisted for the 2004 International Dublin Literary Award.

María Rosa Luna Henson or "Lola Rosa" was the first Filipina who made public in 1992 her story as a comfort woman for the Imperial Japanese Army during the Second World War.

Kristina "Tina" Paner is a Filipino actress and singer.

Racial passing occurred when a person who was categorized as black - their Race in the United States of America, sought to be accepted or perceived ("passes") as a member of another racial group, usually white. Historically, the term has been used primarily in the United States to describe a black person, especially a Mulatto person who assimilated into the white majority to escape the legal and social conventions of racial segregation and discrimination. In the Antebellum South, passing as white was a temporary disguise used as a means of escaping slavery.

Maria Judea "Maki" Jimenez Pulido-Ilagan is a Filipino journalist and one of the two host of Reporter's Notebook, a current affairs programme on the Philippines terrestrial television channel GMA Network with Jiggy Manicad. Pulido was an anchor for the afternoon daily newscast on GMA News TV entitled Balita Pilipinas Ngayon, alongside Mark Salazar. She now currently co-anchors State of the Nation with Atom Araullo.

Tomas Alexander Asuncion Tizon was a Filipino-American author and Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist. His book Big Little Man, a memoir and cultural history, explores themes related to race, masculinity, and personal identity. Tizon taught at the University of Oregon School of Journalism and Communication. His final story, titled "My Family's Slave", was published as the cover story of the June 2017 issue of The Atlantic after his death, sparking significant debate.

Alexandra Swe Wagner is an American television host. She is the host of Alex Wagner Tonight on MSNBC and the author of FutureFace: A Family Mystery, an Epic Quest, and the Secret to Belonging. She was a contributor for CBS News and is a contributing editor at The Atlantic. In 2022, she hosted the first season of Netflix's The Mole reboot. Previously, she was the anchor of the daytime program Now with Alex Wagner (2011–2015) on MSNBC and the co-host of The Circus on Showtime. From November 2016 until March 2018, she was a TV co-anchor on CBS This Morning Saturday. She has also been a senior editor at The Atlantic magazine since April 2016.

Jasmine Casandra Curtis-Smith is a Filipino actress. She is known internationally for her critically acclaimed performance in Hannah Espia's 2013 film Transit, and in the Philippines as the younger sister of fellow actress Anne Curtis. She is currently under Sparkle and as an exclusive artist of GMA Network.

Kalyeserye was a soap opera parody segment that was aired live on the Filipino noontime variety show Eat Bulaga! on GMA Network. The show-within-a-show, as it had evolved, focused on AlDub, the fictional couple pairing of Alden Richards and Maine Mendoza's "Yaya Dub" character in which the two only communicate through lip-syncing to various pop songs and movie audio clips as well as written messages, and interact only on the show's split-screen frame. Richards is usually based in Broadway Centrum studio of Eat Bulaga! in Quezon City, Metro Manila while Mendoza travels around to a different external location.

"Cat Person" is a short story by Kristen Roupenian that was first published in December 2017 in The New Yorker before going viral online. The BBC described the short story as "being shared widely online as social media users discuss how much it relates to modern-day dating".

"Who Is the Bad Art Friend?" is a 2021 New York Times Magazine feature story by Robert Kolker about a feud between two writers, Dawn Dorland and Sonya Larson. The piece focused on accusations that GrubStreet employee Sonya Larson had included a letter written by former GrubStreet instructor Dawn Dorland in her short story The Kindest. Though Dorland and Larson had been involved in ongoing lawsuits since 2018 and the story of their feud had been covered by the media before, Kolker's piece went viral and led to ongoing scrutiny of the case.

References

- ↑ Goldberg, Jeffrey (June 2017). "Editor's Note: A Reporter's Final Story". The Atlantic .

- ↑ "Alex Tizon's posthumous Atlantic cover story is about his family's secret slave", by Eder Campuzano, at The Oregonian ; published May 16, 2017; retrieved May 16, 2017

- ↑ lola in Tagalog Dictionary.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tizon, Alex (June 2017). "My Family's Slave". The Atlantic .

- 1 2 Moran, Romeo (May 17, 2017). "Non-Filipinos need to chill out a bit over Alex Tizon's essay". Scout.

- 1 2 "In 'Lola's Story', a Journalist Reveals a Family Secret". Morning Edition . NPR. May 16, 2017. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ↑ "A recommendation; 'My Family's Slave'". NBC News . May 17, 2017. Retrieved June 28, 2017.

- ↑ Smith, Rosa Inocencio (May 17, 2017). "Your Responses to 'My Family's Slave'". The Atlantic .

- ↑ Reyes, Therese (May 17, 2017). "Filipinos are defending Alex Tizon from Western backlash to his story "My Family's Slave"". Quartz . Retrieved June 29, 2017.

- ↑ Stevens, Heidi (May 17, 2017). "'My Family's Slave' is haunting, essential reading". Chicago Tribune .

- ↑ Bonazzo, John (May 16, 2017). "'Disgusted' Women, Minorities Criticize Viral Atlantic Story 'My Family's Slave'". New York Observer .

- ↑ Herron, Antwan (May 18, 2017). "Like most accounts of slaves and the families they died serving, Alex Tizon's 'My Family's Slave' seems more about mitigating the feelings of the oppressor than rendering visible the life of the oppressed". Wear Your Voice. Archived from the original on May 16, 2020.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Herreria, Carla (May 18, 2017). "3 Filipina-American Journalists Discuss 'My Family's Slave' And Who Gets To Judge It". The Huffington Post .

- ↑ Schmidt, Samantha (May 18, 2017). "Her obituary was missing one painful fact: She was a family's slave". The Washington Post .

- 1 2 Galang, M. Evelina (May 21, 2017). What the Conversation Around Alex Tizon's Atlantic Essay Is Missing. Slate.

- ↑ "'I wrote about slavery as a love story': Writer horrified after realizing she wrote obituary about family slave". Washington Post at the National Post. May 18, 2017. Retrieved June 29, 2017.

- ↑ Ribay, Randy (June 6, 2017). What the Backlash to 'My Family's Slave' Obscured. The Atlantic.