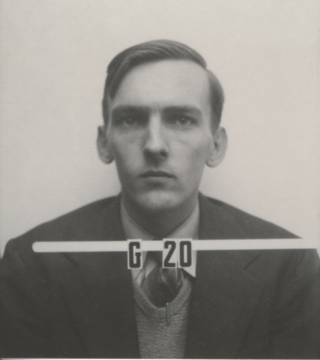

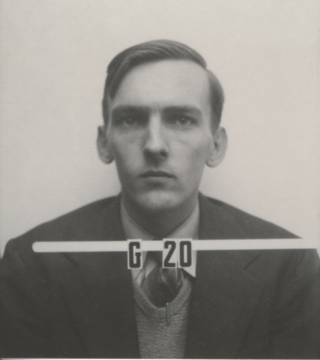

Klaus Emil Julius Fuchs was a German theoretical physicist and atomic spy who supplied information from the American, British, and Canadian Manhattan Project to the Soviet Union during and shortly after World War II. While at the Los Alamos Laboratory, Fuchs was responsible for many significant theoretical calculations relating to the first nuclear weapons and, later, early models of the hydrogen bomb. After his conviction in 1950, he served nine years in prison in the United Kingdom, then migrated to East Germany where he resumed his career as a physicist and scientific leader.

Stanisław Marcin Ulam was a Polish Jewish mathematician, nuclear physicist and computer scientist. He participated in the Manhattan Project, originated the Teller–Ulam design of thermonuclear weapons, discovered the concept of the cellular automaton, invented the Monte Carlo method of computation, and suggested nuclear pulse propulsion. In pure and applied mathematics, he proved some theorems and proposed several conjectures.

Trinity was the code name of the first detonation of a nuclear weapon, conducted by the United States Army at 5:29 a.m. MWT on July 16, 1945, as part of the Manhattan Project. The test was of an implosion-design plutonium bomb, nicknamed the "gadget", of the same design as the Fat Man bomb later detonated over Nagasaki, Japan, on August 9, 1945. Concerns about whether the complex Fat Man design would work led to a decision to conduct the first nuclear test. The code name "Trinity" was assigned by J. Robert Oppenheimer, the director of the Los Alamos Laboratory, inspired by the poetry of John Donne.

Edwin Mattison McMillan was an American physicist credited with being the first to produce a transuranium element, neptunium. For this, he shared the 1951 Nobel Prize in Chemistry with Glenn Seaborg.

Nicholas Constantine Metropolis was a Greek-American physicist.

James Leslie Tuck was a British physicist, working on the applications of explosives as part of the British delegation to Manhattan Project.

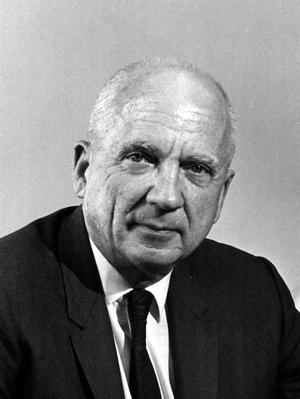

Norris Edwin Bradbury, was an American physicist who served as director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory for 25 years from 1945 to 1970. He succeeded Robert Oppenheimer, who personally chose Bradbury for the position of director after working closely with him on the Manhattan Project during World War II. Bradbury was in charge of the final assembly of "the Gadget", detonated in July 1945 for the Trinity test.

Seth Henry Neddermeyer was an American physicist who co-discovered the muon, and later championed the implosion-type nuclear weapon while working on the Manhattan Project at the Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II.

Robert Fox Bacher was an American nuclear physicist and one of the leaders of the Manhattan Project. Born in Loudonville, Ohio, Bacher obtained his undergraduate degree and doctorate from the University of Michigan, writing his 1930 doctoral thesis under the supervision of Samuel Goudsmit on the Zeeman effect of the hyperfine structure of atomic levels. After graduate work at the California Institute of Technology (Caltech) and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), he accepted a job at Columbia University. In 1935 he accepted an offer from Hans Bethe to work with him at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. It was there that Bacher collaborated with Bethe on his book Nuclear Physics. A: Stationary States of Nuclei (1936), the first of three books that would become known as the "Bethe Bible".

Gun-type fission weapons are fission-based nuclear weapons whose design assembles their fissile material into a supercritical mass by the use of the "gun" method: shooting one piece of sub-critical material into another. Although this is sometimes pictured as two sub-critical hemispheres driven together to make a supercritical sphere, typically a hollow projectile is shot onto a spike, which fills the hole in its center. Its name is a reference to the fact that it is shooting the material through an artillery barrel as if it were a projectile.

Donald William Kerst was an American physicist who worked on advanced particle accelerator concepts and plasma physics. He is most notable for his development of the betatron, a novel type of particle accelerator used to accelerate electrons.

Matthew Linzee Sands was an American physicist and educator best known as a co-author of the Feynman Lectures on Physics. A graduate of Rice University, Sands served with the Naval Ordnance Laboratory and the Manhattan Project's Los Alamos Laboratory during World War II.

Paul Olum was an American mathematician, professor of mathematics, and university administrator.

Elizabeth Monroe Boggs was an American policy maker, scholar, and advocate for people with developmental disabilities. The University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey named "The Elizabeth M. Boggs Center on Developmental Disabilities" in late 1997 in her honor.

James Collyer Keck was an American physicist and engineer recognized for his work on the Manhattan Project and for developing new methods for combustion engine modeling and high temperature flows. Keck was the Ford Professor of Engineering at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and a member of the National Academy of Engineering.

George Thomas Reynolds was an American physicist best known for his accomplishments in particle physics, biophysics and environmental science.

Lawrence Harding Johnston was an American physicist, a young contributor to the Manhattan Project. He was the only man to witness all three atomic explosions in 1945: the Trinity nuclear test in New Mexico and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan.

Darol Kenneth Froman was the deputy director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory from 1951 to 1962. He served as a group leader from 1943 to 1945, and a division head from 1945 to 1948. He was the scientific director of the Operation Sandstone nuclear tests at Enewetak Atoll in the Pacific in 1948, and assistant director for weapons development from 1949 to 1951.

Jane Hamilton Hall was an American physicist. During World War II she worked on the Manhattan Project. After the war she remained at the Los Alamos National Laboratory, where she oversaw the construction and start up of the Clementine nuclear reactor. She became assistant director of the laboratory in 1958. She was secretary of the General Advisory Committee of the Atomic Energy Commission from 1956 until 1959, and was a member of the committee from 1966 to 1972.