Related Research Articles

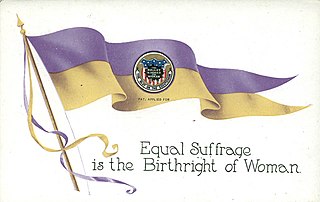

The Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution prohibits the United States and its states from denying the right to vote to citizens of the United States on the basis of sex, in effect recognizing the right of women to vote. The amendment was the culmination of a decades-long movement for women's suffrage in the United States, at both the state and national levels, and was part of the worldwide movement towards women's suffrage and part of the wider women's rights movement. The first women's suffrage amendment was introduced in Congress in 1878. However, a suffrage amendment did not pass the House of Representatives until May 21, 1919, which was quickly followed by the Senate, on June 4, 1919. It was then submitted to the states for ratification, achieving the requisite 36 ratifications to secure adoption, and thereby go into effect, on August 18, 1920. The Nineteenth Amendment's adoption was certified on August 26, 1920.

The National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) was an organization formed on February 18, 1890, to advocate in favor of women's suffrage in the United States. It was created by the merger of two existing organizations, the National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) and the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA). Its membership, which was about seven thousand at the time it was formed, eventually increased to two million, making it the largest voluntary organization in the nation. It played a pivotal role in the passing of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which in 1920 guaranteed women's right to vote.

The League of Women Voters (LWV) is an American nonprofit, nonpartisan political organization. Founded in 1920, its ongoing major activities include registering voters, providing voter information, and advocating for voting rights. In addition, the LWV works with partners that share its positions and supports a variety of progressive public policy positions, including campaign finance reform, women's rights, health care reform, gun control and LGBT+ rights.

Carrie Chapman Catt was an American women's suffrage leader who campaigned for the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, which gave U.S. women the right to vote in 1920. Catt served as president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association from 1900 to 1904 and 1915 to 1920. She founded the League of Women Voters in 1920 and the International Woman Suffrage Alliance in 1904, which was later named International Alliance of Women. She "led an army of voteless women in 1919 to pressure Congress to pass the constitutional amendment giving them the right to vote and convinced state legislatures to ratify it in 1920". She "was one of the best-known women in the United States in the first half of the twentieth century and was on all lists of famous American women."

The National Woman's Party (NWP) was an American women's political organization formed in 1916 to fight for women's suffrage. After achieving this goal with the 1920 adoption of the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, the NWP advocated for other issues including the Equal Rights Amendment. The most prominent leader of the National Woman's Party was Alice Paul, and its most notable event was the 1917–1919 Silent Sentinels vigil outside the gates of the White House.

Lucy Burns was an American suffragist and women's rights advocate. She was a passionate activist in the United States and the United Kingdom, who joined the militant suffragettes. Burns was a close friend of Alice Paul, and together they ultimately formed the National Woman's Party.

Women's suffrage, or the right to vote, was established in the United States over the course of more than half a century, first in various states and localities, sometimes on a limited basis, and then nationally in 1920 with the ratification of the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution.

The Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage was an American organization formed in 1913 led by Alice Paul and Lucy Burns to campaign for a constitutional amendment guaranteeing women's suffrage. It was inspired by the United Kingdom's suffragette movement, which Paul and Burns had taken part in. Their continuous campaigning drew attention from congressmen, and in 1914 they were successful in forcing the amendment onto the floor for the first time in decades.

Laura Clay, co-founder and first president of the Kentucky Equal Rights Association, was a leader of the American women's suffrage movement. She was one of the most important suffragists in the South, favoring the states' rights approach to suffrage. A powerful orator, she was active in the Democratic Party and had important leadership roles in local, state and national politics. In 1920 at the Democratic National Convention, she was one of two women, alongside Cora Wilson Stewart, to be the first women to have their names placed into nomination for the presidency at the convention of a major political party.

Woman's Journal was an American women's rights periodical published from 1870 to 1931. It was founded in 1870 in Boston, Massachusetts, by Lucy Stone and her husband Henry Browne Blackwell as a weekly newspaper. In 1917 it was purchased by Carrie Chapman Catt's Leslie Woman Suffrage Commission and merged with The Woman Voter and National Suffrage News to become known as The Woman Citizen. It served as the official organ of the National American Woman Suffrage Association until 1920, when the organization was reformed as the League of Women Voters, and the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution was passed granting women the right to vote. Publication of Woman Citizen slowed from weekly, to bi-weekly, to monthly. In 1927, it was renamed The Woman's Journal. It ceased publication in June 1931.

Emma Smith DeVoe was an American women suffragist in the early twentieth century, changing the face of politics for both women and men alike. When she died, the Tacoma News Tribune called her Washington state's "Mother of Women's Suffrage".

The Woman Suffrage Procession on March 3, 1913, was the first suffragist parade in Washington, D.C. It was also the first large, organized march on Washington for political purposes. The procession was organized by the suffragists Alice Paul and Lucy Burns for the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Planning for the event began in Washington in December 1912. As stated in its official program, the parade's purpose was to "march in a spirit of protest against the present political organization of society, from which women are excluded."

Florence Brooks Whitehouse was an American suffragist, activist and novelist from Maine. In 2008, Whitehouse was inducted to the Maine Women's Hall of Fame. She was an early feminist who was considered radical for her support of Alice Paul and the tactics of the National Woman's Party.

This timeline highlights milestones in women's suffrage in the United States, particularly the right of women to vote in elections at federal and state levels.

This is a timeline of women's suffrage in Montana. The fight for women's suffrage in Montana started earlier, before even Montana became a state. In 1887, women gained the right to vote in school board elections and on tax issues. In the years that followed, women battled for full, equal suffrage, which culminated in a year-long campaign in 1914 when they became one of eleven states with equal voting rights for most women. Montana ratified the Nineteenth Amendment on August 2, 1919 and was the thirteenth state to ratify. Native American women voters did not have equal rights to vote until 1924.

Women's suffrage began in Delaware the late 1860s, with efforts from suffragist, Mary Ann Sorden Stuart, and an 1869 women's rights convention held in Wilmington, Delaware. Stuart, along with prominent national suffragists lobbied the Delaware General Assembly to amend the state constitution in favor of women's suffrage. Several suffrage groups were formed early on, but the Delaware Equal Suffrage Association (DESA) formed in 1896, would become one of the major state suffrage clubs. Suffragists held conventions, continued to lobby the government and grow their movement. In 1913, a chapter of the Congressional Union (CU), which would later be known at the National Woman's Party (NWP), was set up by Mabel Vernon in Delaware. NWP advocated more militant tactics to agitate for women's suffrage. These included picketing and setting watchfires. The Silent Sentinels protested in Washington, D.C., and were arrested for "blocking traffic." Sixteen women from Delaware, including Annie Arniel and Florence Bayard Hilles, were among those who were arrested. During World War I, both African-American and white suffragists in Delaware aided the war effort. During the ratification process for the Nineteenth Amendment, Delaware was in the position to become the final state needed to complete ratification. A huge effort went into persuading the General Assembly to support the amendment. Suffragists and anti-suffragists alike campaigned in Dover, Delaware for their cause. However, Delaware did not ratify the Nineteenth Amendment until March 6, 1923, well after it was already part of the United States Constitution.

Women's suffrage began in Hawaii in the 1890s. However, when the Hawaiian Kingdom ruled, women had roles in the government and could vote in the House of Nobles. After the overthrow of Queen Liliʻuokalani in 1893, women's roles were more restricted. Suffragists, Wilhelmine Kekelaokalaninui Widemann Dowsett and Emma Kaili Metcalf Beckley Nakuina, immediately began working towards women's suffrage. The Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) of Hawaii also advocated for women's suffrage in 1894. As Hawaii was being annexed as a US territory in 1899, racist ideas about the ability of Native Hawaiians to rule themselves caused problems with allowing women to vote. Members of the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) petitioned the United States Congress to allow women's suffrage in Hawaii with no effect. Women's suffrage work picked up in 1912 when Carrie Chapman Catt visited Hawaii. Dowsett created the National Women's Equal Suffrage Association of Hawai'i that year and Catt promised to act as the delegate for NAWSA. In 1915 and 1916, Prince Jonah Kūhiō Kalanianaʻole brought resolutions to the U.S. Congress requesting women's suffrage for Hawaii. While there were high hopes for the effort, it was not successful. In 1919, suffragists around Hawaii met for mass demonstrations to lobby the territorial legislature to pass women's suffrage bills. These were some of the largest women's suffrage demonstrations in Hawaii, but the bills did not pass both houses. Women in Hawaii were eventually franchised through the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment.

The movement for women's suffrage in Arizona began in the late 1800s. After women's suffrage was narrowly voted down at the 1891 Arizona Constitutional Convention, prominent suffragettes such as Josephine Brawley Hughes and Laura M. Johns formed the Arizona Suffrage Association and began touring the state campaigning for women's right to vote. Momentum built throughout the decade, and after a strenuous campaign in 1903, a woman's suffrage bill passed both houses of the legislature but was ultimately vetoed by Governor Alexander Oswald Brodie.

In 1893, Colorado became the second state in the United States to grant women's suffrage and the first to do so through a voter referendum. Even while Colorado was a territory, lawmakers and other leaders tried to include women's suffrage in laws and later in the state constitution. The constitution did give women the right to vote in school board elections. The first voter referendum campaign was held in 1877. The Woman Suffrage Association of Colorado worked to encourage people to vote yes. Nationally-known suffragists, such as Susan B. Anthony and Lucy Stone spoke alongside Colorado's own Alida Avery around the state. Despite the efforts to influence voters, the referendum failed. Suffragists continued to grow support for women's right to vote. They exercised their right to vote in school board elections and ran for office. In 1893, another campaign for women's suffrage took place. Both Black and white suffragists worked to influence voters, gave speeches, and turned out on election day in a last-minute push. The effort was successful and women earned equal suffrage. In 1894, Colorado again made history by electing three women to the Colorado house of representatives. After gaining the right to vote, Colorado women continued to fight for suffrage in other states. Some women became members of the Congressional Union (CU) and pushed for a federal suffrage amendment. Colorado women also used their right to vote to pass reforms in the state and to support women candidates.

References

- 1 2 3 "Women's History – ODU Special Collections Blog". 2022-11-07. Retrieved 2024-03-08.

- 1 2 "The League of Women Voters: A Century of Voter Engagement | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History". www.gilderlehrman.org. Retrieved 2024-03-08.

- ↑ "Woman Suffrage in the West (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2024-03-26.

- ↑ "The History of Voting and Elections in Washington State". www2.sos.wa.gov. Retrieved 2024-03-26.

- ↑ "National Council of Woman Voters". Washington State Historical Society. Archived from the original on November 23, 2018.

- 1 2 3 Ross-Nazzal, Jennifer (Spring 2005). "Emma Smith DeVoe: Practicing Pragmatic Politics in the Pacific Northwest". The Pacific Northwest Quarterly . 96 (2): 76–84. JSTOR 40491835 – via JSTOR.

- 1 2 3 Ross-Nazzal, Jennifer M. (2011). Winning the West for Women: The Life of Suffragist Emma Smith DeVoe. Seattle: University of Washington Press. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-295-99086-6. OCLC 670324868.

- ↑ "Women's suffrage · The Gilded Age and Progressive Era: Student Research Projects · Digital Exhibits". digitalexhibits.libraries.wsu.edu. Retrieved 2024-04-10.