Related Research Articles

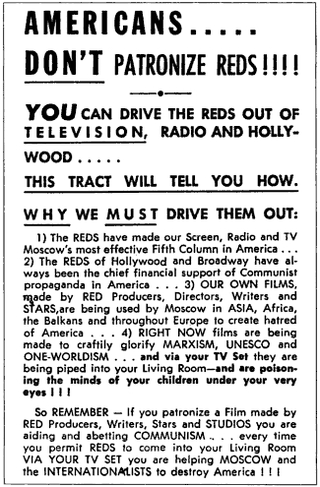

McCarthyism, also known as the Second Red Scare, was the political repression and persecution of left-wing individuals and a campaign spreading fear of alleged communist and Soviet influence on American institutions and of Soviet espionage in the United States during the late 1940s through the 1950s. After the mid-1950s, U.S. Senator Joseph McCarthy, who had spearheaded the campaign, gradually lost his public popularity and credibility after several of his accusations were found to be false. The U.S. Supreme Court under Chief Justice Earl Warren made a series of rulings on civil and political rights that overturned several key laws and legislative directives, and helped bring an end to the Second Red Scare. Historians have suggested since the 1980s that as McCarthy's involvement was less central than that of others, a different and more accurate term should be used instead that more accurately conveys the breadth of the phenomenon, and that the term McCarthyism is, in the modern day, outdated. Ellen Schrecker has suggested that Hooverism, after FBI Head J. Edgar Hoover, is more appropriate.

The National Lawyers Guild (NLG) is a progressive public interest association of lawyers, law students, paralegals, jailhouse lawyers, law collective members, and other activist legal workers, in the United States. The group was founded in 1937 as an alternative to the American Bar Association (ABA) in protest of that organization's exclusionary membership practices and conservative political orientation. They were the first predominantly white US bar association to allow the admission of minorities to their ranks. The group sought to bring more lawyers closer to the labor movement and progressive political activities, to support and encourage lawyers otherwise "isolated and discouraged," and to help create a "united front" against Fascism.

The Communist Party USA, ideologically committed to foster a socialist revolution in the United States, played a significant role in defending the civil rights of African Americans during its most influential years of the 1930s and 1940s. In that period, the African-American population was still concentrated in the South, where it was largely disenfranchised, excluded from the political system, and oppressed under Jim Crow laws.

Red Channels: The Report of Communist Influence in Radio and Television was an anti-Communist document published in the United States at the start of the 1950s. Issued by the right-wing journal Counterattack on June 22, 1950, the pamphlet-style book names 151 actors, writers, musicians, broadcast journalists, and others in the context of purported Communist manipulation of the entertainment industry. Some of the 151 were already being denied employment because of their political beliefs, history, or association with suspected subversives. Red Channels effectively placed the rest on a blacklist.

The Civil Rights Congress (CRC) was a United States civil rights organization, formed in 1946 at a national conference for radicals and disbanded in 1956. It succeeded the International Labor Defense, the National Federation for Constitutional Liberties, and the National Negro Congress, serving as a defense organization. Beginning about 1948, it became involved in representing African Americans sentenced to death and other highly prominent cases, in part to highlight racial injustice in the United States. After Rosa Lee Ingram and her two teenage sons were sentenced in Georgia, the CRC conducted a national appeals campaign on their behalf, their first for African Americans.

Bartley Crum was an American lawyer who became prominent as a member of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry, his book on that experience, and for defending targets of HUAC, particularly the Hollywood Ten and Paul Robeson.

The National Negro Congress (NNC) was an American organization formed in 1936 at Howard University as a broadly based organization with the goal of fighting for Black liberation; it was the successor to the League of Struggle for Negro Rights, both affiliated with the Communist Party. During the Great Depression, the party worked in the United States to unite black and white workers and intellectuals in the fight for racial justice. This period represented the Party's peak of prestige in African-American communities. NNC was opposed to war, fascism, and discrimination, especially racial discrimination. During the Great Depression era, a majority of Americans faced immense economic problems. Many lost their jobs and as a result, were forced to live at the margins of society. The crisis highlighted inequities for many African Americans, who were unemployed at higher rates than white.

The National Negro Labor Council (1950–1955) was an advocacy group dedicated to serving the needs and civil rights of black workers. Many union leaders of the CIO and AFL considered it a Communist front. In 1951 it was officially branded a communist front organization by U.S. attorney general Herbert Brownwell.

Manning Rudolph Johnson AKA Manning Johnson and Manning R. Johnson was a Communist Party USA African-American leader and the party's candidate for U.S. Representative from New York's 22nd congressional district during a special election in 1935. Later, he left the Party and became an anti-communist government informant and witness.

The House Committee on Un-American Activities (HCUA), popularly the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), was an investigative committee of the United States House of Representatives, created in 1938 to investigate alleged disloyalty and subversive activities on the part of private citizens, public employees, and those organizations suspected of having communist ties. It became a standing (permanent) committee in 1946, and from 1969 onwards it was known as the House Committee on Internal Security. When the House abolished the committee in 1975, its functions were transferred to the House Judiciary Committee.

The Abraham Lincoln School for Social Science in Chicago, Illinois was a "broad, nonpartisan school for workers, writers, and their sympathizers," aimed at the thousands of African-American workers who had migrated to Chicago from the American South during the 1930s and 1940s.

During the ten decades since its establishment in 1919, the Communist Party USA produced or inspired a vast array of newspapers and magazines in the English language.

The United Public Workers of America (1946–1952) was an American labor union representing federal, state, county, and local government employees. The union challenged the constitutionality of the Hatch Act of 1939, which prohibited federal executive branch employees from engaging in politics. In United Public Workers of America v. Mitchell, 330 U.S. 75 (1947), the Supreme Court of the United States upheld the Hatch Act, finding that its infringement on the Constitutional rights was outweighed by the need to end political corruption. The union's leadership was Communist, and in a famous purge the union was ejected from its parent trade union federation, the Congress of Industrial Organizations, in 1950.

The International Labor Defense (ILD) (1925–1947) was a legal advocacy organization established in 1925 in the United States as the American section of the Comintern's International Red Aid network. The ILD defended Sacco and Vanzetti, was active in the anti-lynching, movements for civil rights, and prominently participated in the defense and legal appeals in the cause célèbre of the Scottsboro Boys in the early 1930s. Its work contributed to the appeal of the Communist Party among African Americans in the South. In addition to fundraising for defense and assisting in defense strategies, from January 1926 it published Labor Defender, a monthly illustrated magazine that achieved wide circulation. In 1946 the ILD was merged with the National Federation for Constitutional Liberties to form the Civil Rights Congress, which served as the new legal defense organization of the Communist Party USA. It intended to expand its appeal, especially to African Americans in the South. In several prominent cases in which blacks had been sentenced to death in the South, the CRC campaigned on behalf of black defendants. It had some conflict with former allies, such as the NAACP, and became increasingly isolated. Because of federal government pressure against organizations it considered subversive, such as the CRC, it became less useful in representing defendants in criminal justice cases. The CRC was dissolved in 1956. At the same time, in this period, black leaders were expanding the activities and reach of the Civil Rights Movement. In 1954, in a case managed by the NAACP, the US Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional.

The National Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners (NCDPP) was an organization founded in June 1931 as an accompaniment to the International Labor Defense, led by the Communist Party of the United States of America. The NCDPP was originally called the Emergency Committee for Southern Political Prisoners (ECSPP).

American Committee for the Protection of Foreign Born was the successor group to the National Council for the Protection of the Foreign Born and its successor, seen by the US federal government as subversive for "protecting foreign Communists who come to this country," thus "enabling them to operate here.".

Thomas I. Emerson (1907–1991) was a 20th-century American attorney and professor of law. He is known as a "major architect of civil liberties law," "arguably the foremost First Amendment scholar of his generation," and "pillar of the Bill of Rights."

Freedom was a monthly newspaper focused on African-American issues published from 1950 to 1955. The publication was associated primarily with the internationally renowned singer, actor and then officially disfavored activist Paul Robeson, whose column, with his photograph, ran on most of its front pages. Freedom's motto was: "Where one is enslaved, all are in chains!" The newspaper has been described as "the most visible African American Left cultural institution during the early 1950s." In another characterization, "Freedom paper was basically an attempt by a small group of black activists, most of them Communists, to provide Robeson with a base in Harlem and a means of reaching his public... The paper offered more coverage of the labor movement than nearly any other publication, particularly of the left-led unions that were expelled from the CIO in the late 1940s... [It] encouraged its African American readership to identify its struggles with anti-colonial movements in Africa, Asia, and the Caribbean. Freedom gave extensive publicity to... the struggle against apartheid."

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Guide to the George Marshall Papers" (PDF). Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ↑ Press releases, December 4, 1947 and September 21, 1948; cited in report prepared from the public files of the House Committee on Un-American Activities for Senator William E. Jenner, Chairman of the Senate Subcommittee on Internal Security, October 20, 1953, reproduced in Who Was Frank Marshall Davis?, Cliff Kincaid and Herbert Romerstein, p. 12-14.

- ↑ M. Stanton Evans, Blacklisted by History: The Untold Story of Senator Joe McCarthy and His Fight Against America's Enemies (New York: Crown Forum, 2007) ISBN 978-1-4000-8105-9, pp. 55-60, notes).

- ↑ "Prelude to McCarthyism: The Making of a Blacklist". Goldstein, Robert Justin, Prologue, U.S. National Archives. 2006. Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ↑ Jones, Elton (1996). Which Bible?. Health Research Books. p. 106. ISBN 9780787304829 . Retrieved 3 March 2015.

- ↑ No relation to General George C. Marshall, the Secretary of State.

- ↑ "George Marshall papers 1933-1955". New York Public Library. 2009. Retrieved 2 December 2019.

- ↑ New York Times, "George Marshall, 96, Pioneer in the Civil Rights Movement" [obituary], June 18, 2000.

- ↑ New York Times, June 18, 2000.