Related Research Articles

The Bodhisattvacaryāvatāra or Bodhicaryāvatāra translated into English as A Guide to the Bodhisattva's Way of Life, is a Mahāyāna Buddhist text written c. 700 AD in Sanskrit verse by Shantideva (Śāntideva), a Buddhist monk at Nālandā Monastic University in India which is also where it was composed.

Mādhyamaka, otherwise known as Śūnyavāda and Niḥsvabhāvavāda, refers to a tradition of Buddhist philosophy and practice founded by the Indian Buddhist monk and philosopher Nāgārjuna. The foundational text of the Mādhyamaka tradition is Nāgārjuna's Mūlamadhyamakakārikā. More broadly, Mādhyamaka also refers to the ultimate nature of phenomena as well as the non-conceptual realization of ultimate reality that is experienced in meditation.

Mahāyāna-sūtrālamkāra-kārikā is a major work of Buddhist philosophy attributed to Maitreya-nātha which is said to have transmitted it to Asanga. The Mahāyāna-sūtrālamkāra, written in verse, presents the Mahayana path from the Yogacara perspective. It comprises twenty-two chapters with a total of 800 verses and shows considerable similarity in arrangement and content to the Bodhisattvabhūmiśāstra, although the interesting first chapter proving the validity and authenticity of Mahāyāna is unique to this work. Associated with it is a prose commentary (bhāṣya) by Vasubandhu and several sub-commentaries by Sthiramati and others; the portions by Maitreya-nātha and Vasubandhu both survive in Sanskrit as well as Tibetan, Chinese, and Mongolian translations.

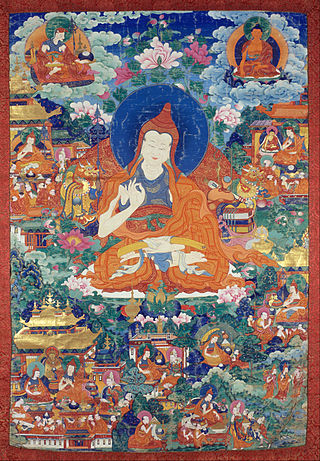

Tsongkhapa was an influential Tibetan Buddhist monk, philosopher and tantric yogi, whose activities led to the formation of the Gelug school of Tibetan Buddhism. He is also known by his ordained name Losang Drakpa or simply as "Je Rinpoche". He is also known by Chinese as Zongkapa Lobsang Zhaba or just Zōngkābā (宗喀巴).

Thrangu Rinpoche was born in Kham, Tibet. He was deemed to be a prominent tulku in the Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism, the ninth reincarnation in his particular line. His full name and title was the Very Venerable Ninth Khenchen Thrangu Tulku, Karma Lodrö Lungrik Maway Senge. The academic title Khenchen denotes great scholarly accomplishment, and the term Rinpoche is a Tibetan devotional title which may be accorded to respected teachers and exemplars.

The Buddhist doctrine of the two truths differentiates between two levels of satya in the teaching of the Śākyamuni Buddha: the "conventional" or "provisional" (saṁvṛti) truth, and the "ultimate" (paramārtha) truth.

Jamgön Kongtrül Lodrö Thayé, also known as Jamgön Kongtrül the Great, was a Tibetan Buddhist scholar, poet, artist, physician, tertön and polymath. He is credited as one of the founders of the Rimé movement (non-sectarian), compiling what is known as the "Five Great Treasuries". He achieved great renown as a scholar and writer, especially among the Nyingma and Kagyu lineages and composed over 90 volumes of Buddhist writing, including his magnum opus, The Treasury of Knowledge.

Jamgön Ju Mipham Gyatso, or Mipham Jamyang Namgyal Gyamtso (1846–1912) was a very influential philosopher and polymath of the Nyingma school of Tibetan Buddhism. He wrote over 32 volumes on topics such as painting, poetics, sculpture, alchemy, medicine, logic, philosophy and tantra. Mipham's works are still central to the scholastic curriculum in Nyingma monasteries today. Mipham is also considered one of the leading figures in the Rimé (non-sectarian) movement in Tibet.

Khenpo Tsültrim Gyamtso Rinpoche is a prominent scholar yogi in the Kagyu tradition of Tibetan Buddhism. He teaches widely in the West, often through songs of realization, his own as well as those composed by Milarepa and other masters of the past. "Tsültrim Gyamtso" translates to English as "Ocean of Ethical Conduct".

The Svātantrika–Prāsaṅgika distinction is a doctrinal distinction made within Tibetan Buddhism between two stances regarding the use of logic and the meaning of conventional truth within the presentation of Madhyamaka.

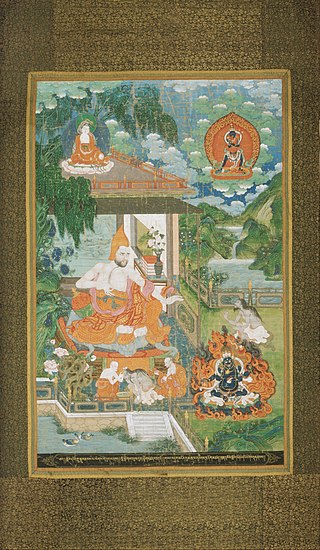

Śāntarakṣita, whose name translates into English as "protected by the One who is at peace" was an important and influential Indian Buddhist philosopher, particularly for the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. Śāntarakṣita was a philosopher of the Madhyamaka school who studied at Nalanda monastery under Jñānagarbha, and became the founder of Samye, the first Buddhist monastery in Tibet.

Bhāviveka, also called Bhāvaviveka, and Bhavya was a sixth-century madhyamaka Buddhist philosopher. Alternative names for this figure also include Bhavyaviveka, Bhāvin, Bhāviviveka, Bhagavadviveka and Bhavya. Bhāviveka is the author of the Madhyamakahrdaya, its auto-commentary the Tarkajvālā and the Prajñāpradīpa.

Pramana literally means "proof" and "means of knowledge". In Indian philosophies, pramana are the means which can lead to knowledge, and serve as one of the core concepts in Indian epistemology. It has been one of the key, much debated fields of study in Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism since ancient times. It is a theory of knowledge, and encompasses one or more reliable and valid means by which human beings gain accurate, true knowledge. The focus of pramana is how correct knowledge can be acquired, how one knows, how one does not know, and to what extent knowledge pertinent about someone or something can be acquired.

Vairotsana was a lotsawa or "translator" living during the reign of King Trisong Detsen, who ruled 755-97 CE. Vairotsana, one of the 25 main disciples of Padmasambhava, was recognized by the latter as a reincarnation of an Indian pandita. He was among the first seven monks ordained by Śāntarakṣita, and was sent to Dhahena in India to study with Śrī Siṅgha, who taught him in complete secrecy. Śrī Siṅgha in turn entrusted Vairotsana with the task of propagating the semde and longdé sections of Dzogchen in Tibet. He is one of the three main masters to bring the Dzogchen teachings to Tibet, the two others being Padmasambhava and Vimalamitra, and was also a significant lineage holder of trul khor.

Shedra is a Tibetan word meaning "place of teaching" but specifically refers to the educational program in Tibetan Buddhist monasteries and nunneries. It is usually attended by monks and nuns between their early teen years and early twenties. Not all young monastics enter a shedra; some study ritual practices instead. Shedra is variously described as a university, monastic college, or philosophy school. The age range of students typically corresponds to both secondary school and college. After completing a shedra, some monks continue with further scholastic training toward a Khenpo or Geshe degree, and other monks pursue training in ritual practices.

Shenlha Ökar or Shiwa Ökar is the most important deity in the Yungdrung Bon tradition of Tibet. He is counted among the "Four Transcendent Lords" along with Satrig Ersang, Sangpo Bumtri, and Tonpa Shenrab Miwoche.

The Madhyamakālaṃkāra is an 8th-century Buddhist text, believed to have been originally composed in Sanskrit by Śāntarakṣita (725–788), which is extant in Tibetan. The Tibetan text was translated from the Sanskrit by Surendrabodhi and Jñānasūtra.

The Madhyamakāvatāra is a text by Candrakīrti on the Mādhyamaka school of Buddhist philosophy. Candrakīrti also wrote an auto-commentary to the work, called the Madhyamakāvatārabhasya.

In the Nyingma Tibetan Buddhist Dharma teachings faith's essence is to make one's being, and perfect dharma, inseparable. The etymology is the aspiration to achieve one's goal. Faith's virtues are like a fertile field, a wishing gem, a king who enforces the law, someone who holds the carefulness stronghold, a boat on a great river and an escort in a dangerous place. Faith in karma causes temporary happiness in the higher realms. Faith is a mental state in the Abhidharma literature's fifty-one mental states. Perfect faith in the Buddha, his Teaching (Dharma) and the Order of his Disciples (Sangha) is comprehending these three jewels of refuge with serene joy based on conviction. The Tibetan word for faith is day-pa, which might be closer in meaning to confidence, or trust.

The mind teachings of Tibet are a body of sacredly held instructions on the nature of mind and the practice of meditation on, or in accordance with, that nature. Although maintained and cultivated, to various degrees, within each of the major Tibetan Buddhist traditions, they are primarily associated with the mahamudra traditions of the Kagyu and the dzogchen traditions of the Nyingma.

References

- Murthy, K. Krishna. Buddhism in Tibet. Sundeep Prakashan (1989) ISBN 81-85067-16-3.

- Doctor, Thomas H. (trans.) Mipham, Jamgon Ju.(author)(2004). Speech of Delight: Mipham's Commentary of Shantarakshita's Ornament of the Middle Way. Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications. ISBN 1-55939-217-7

- Shantarakshita (author); Mipham (commentator); Padmakara Translation Group (translators)(2005). The Adornment of the Middle Way: Shantarakshita's Madhyamakalankara with commentary by Jamgön Mipham. Boston, Massachusetts, USA: Shambhala Publications, Inc. ISBN 1-59030-241-9 (alk. paper)

- Banerjee, Anukul Chandra. Acaraya Santaraksita in Bulletin of Tibetology, New Series No. 3, p. 1-5. (1982). Gangtok, Sikkim Research Institute of Tibetology and Other Buddhist Studies.

- Blumenthal, James. The Ornament of the Middle Way: A Study of the Madhyamaka Thought of Shantarakshita. Snow Lion, (2004). ISBN 1-55939-205-3 - a study and translation of the primary Gelukpa commentary on Shantarakshita's treatise: Gyal-tsab Je's Remembering The Ornament of the Middle Way.

- Prasad, Hari Shankar (ed.). Santaraksita, His Life and Work. (Collected Articles from "All India Seminar on Acarya Santaraksita" held on August 3–5, 2001 at Namdroling Monastery, Mysore, Karnataka). New Delhi, Tibet House, (2003).

- Jha, Ganganath (trans.) The Tattvasangraha of Shantaraksita with the Commentary of Kamalashila. 2 volumes. First Edition : Baroda, (G.O.S. No. Lxxxiii) (1939). Reprint; Motilal Banarsidass, Delhi, (1986).

- Phuntsho, Karma. Mipham's Dialectics and Debates on Emptiness: To Be, Not to Be or Neither. London: RoutledgeCurzon (2005) ISBN 0-415-35252-5