Net metering is an electricity billing mechanism that allows consumers who generate some or all of their own electricity to use that electricity anytime, instead of when it is generated. This is particularly important with renewable energy sources like wind and solar, which are non-dispatchable. Monthly net metering allows consumers to use solar power generated during the day at night, or wind from a windy day later in the month. Annual net metering rolls over a net kilowatt-hour (kWh) credit to the following month, allowing solar power that was generated in July to be used in December, or wind power from March in August.

NRG Energy, Inc. is an American energy company, headquartered in Houston, Texas. It was formerly the wholesale arm of Northern States Power Company (NSP), which became Xcel Energy, but became independent in 2000. NRG Energy is involved in energy generation and retail electricity. Their portfolio includes natural gas generation, coal generation, oil generation, nuclear generation, wind generation, utility-scale generation, and distributed solar generation. NRG serves over 7 million retail customers in 24 US states including Texas, Connecticut, Delaware, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, Ohio; the District of Columbia, and eight provinces in Canada.

The Public Utilities Commission of Ohio (PUCO) is the public utilities commission of the U.S. state of Ohio, charged with the regulation of utility service providers such as those of electricity, natural gas, and telecommunications as well as railroad safety and intrastate hazardous materials transport.

A Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) is a regulation that requires the increased production of energy from renewable energy sources, such as wind, solar, biomass, and geothermal, which have been adopted in 38 of 50 U.S. states and the District of Columbia. The United States federal RPS is called the Renewable Electricity Standard (RES). Several states have clean energy standards, which also allow for resources that do not produce emissions, such as large hydropower and nuclear power.

Financial incentives for photovoltaics are incentives offered to electricity consumers to install and operate solar-electric generating systems, also known as photovoltaics (PV).

A feed-in tariff is a policy mechanism designed to accelerate investment in renewable energy technologies by offering long-term contracts to renewable energy producers. This means promising renewable energy producers an above-market price and providing price certainty and long-term contracts that help finance renewable energy investments. Typically, FITs award different prices to different sources of renewable energy in order to encourage the development of one technology over another. For example, technologies such as wind power and solar PV are awarded a higher price per kWh than tidal power. FITs often include a "digression": a gradual decrease of the price or tariff in order to follow and encourage technological cost reductions.

Electricity pricing can vary widely by country or by locality within a country. Electricity prices are dependent on many factors, such as the price of power generation, government taxes or subsidies, CO

2 taxes, local weather patterns, transmission and distribution infrastructure, and multi-tiered industry regulation. The pricing or tariffs can also differ depending on the customer-base, typically by residential, commercial, and industrial connections.

Solar power has been growing rapidly in the U.S. state of California because of high insolation, community support, declining solar costs, and a renewable portfolio standard which requires that 60% of California's electricity come from renewable resources by 2030, with 100% by 2045. Much of this is expected to come from solar power via photovoltaic facilities or concentrated solar power facilities.

Solar power in New Mexico in 2016 generated 2.8% of the state's total electricity consumption, despite a National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) projection suggesting a potential contribution three orders of magnitude larger.

The energy sector in Hawaii has rapidly adopted solar power due to the high costs of electricity, and good solar resources, and has one of the highest per capita rates of solar power in the United States. Hawaii's imported energy costs, mostly for imported petroleum and coal, are three to four times higher than the mainland, so Hawaii has motivation to become one of the highest users of solar energy. Hawaii was the first state in the United States to reach grid parity for photovoltaics. Its tropical location provides abundant ambient energy.

A community solar project, farm or garden is a solar power installation that accepts capital from and provides output credit and tax benefits to multiple customers, including individuals, businesses, nonprofits, and other investors. Participants typically invest in or subscribe to a certain kW capacity or kWh generation of remote electrical production. The project's power output is credited to investors or subscribers in proportion to their investment, with adjustments to reflect ongoing changes in capacity, technology, costs and electricity rates. Community solar provides direct access to the renewable energy to customers who cannot install it themselves. Companies, cooperatives, governments or non-profits operate the systems.

Net metering is a policy by many states in the United States designed to help the adoption of renewable energy. Net metering was pioneered in the United States as a way to allow solar and wind to provide electricity whenever available and allow use of that electricity whenever it was needed, beginning with utilities in Idaho in 1980, and in Arizona in 1981. In 1983, Minnesota passed the first state net metering law. As of March 2015, 44 states and Washington, D.C. have developed mandatory net metering rules for at least some utilities. However, although the states' rules are clear, few utilities actually compensate at full retail rates.

Solar power in Michigan has been growing in recent years due to new technological improvements, falling solar prices and a variety of regulatory actions and financial incentives. The largest solar farm in Michigan is Assembly Solar, completed in 2022, which has 347 MW of capacity. Small-scale solar provided 50% of Michigan solar electricity as recently as 2020 but multiple solar farms in the 100 MW to 200 MW range are proposed to be completed by the middle of the decade. Although among the lowest U.S. states for solar irradiance, Michigan mostly lies farther south than Germany where solar power is heavily deployed. Michigan is expected to use 120 TWh per year in 2030. To reach a 100% solar electrical grid would require 2.4% of Michigan's land area to host 108 GW of installed capacity.

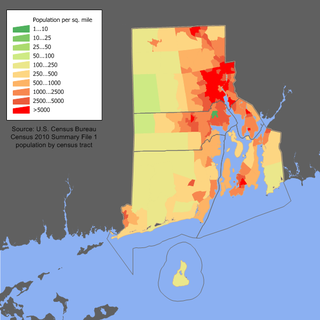

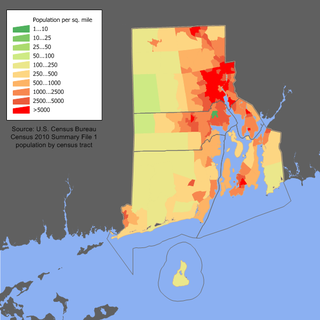

Solar power in Rhode Island has become economical due to new technological improvements and a variety of regulatory actions and financial incentives, particularly a 30% federal tax credit, available through 2016, for any size project. A typical residential installation could pay for itself in utility bill savings in 14 years, and generate a profit for the remainder of its 25 year life. Larger systems, from 10 kW to 5 MW, receive a feed-in tariff of up to 33.45¢/kWh.

Solar power in North Dakota has been a little-used resource. The state ranks last on installed solar power in the United States, with .47 MW of installed capacity. Solar on rooftops can provide 24.6% of all electricity used in North Dakota from 3,300 MW of solar panels. The most cost effective application for solar panels is for pumping water at remote wells where solar panels can be installed for $800 vs. running power lines for $15,000/mile.

Solar power in New Hampshire provides a small percentage of the state's electricity. State renewable requirements and declining prices have led to some installations. Photovoltaics on rooftops can provide 53.4% of all electricity used in New Hampshire, from 5,300 MW of solar panels, and 72% of the electricity used in Concord, New Hampshire. A 2016 estimate suggests that a typical 5 kW system costing $25,000 before credits and utility savings will pay for itself in 9 years, and generate a profit of $34,196 over the rest of its 25-year life. A loan or lease provides a net savings each year, including the first year. New Hampshire has a rebate program which pays $0.75/W for residential systems up to 5 kW, for up to 50% of the system cost, up to $3,750. However, New Hampshire's solar installation lagged behind nearby states such as Vermont and New York, which in 2013 had 10 times and 25 times more solar, respectively.

Solar power in Delaware is small industry. Delaware had 150 MW of total installed capacity in 2020. The largest solar farms in the state included the 10 MW Dover Sun Park and the 12 MW Milford Solar Farm.

Net metering in Nevada is a public policy and political issue surrounding the rates that Nevada public utilities are required to pay to purchase excess energy produced by electric customers who generate their own electricity, such as through rooftop solar panels. The issue centers around the question paying solar customers the retail or wholesale rate for the generated electricity.

Net metering in Arizona is a public policy and political issue regarding the rates that Arizona utility companies pay solar customers sell excess energy back to the electrical grid. The issue has two political sides: utility companies that to pay solar customers the "wholesale rate" for their excess electricity, and solar panel installers and solar customers who want utility companies to pay the "retail rate".

Net metering in New Mexico is a set of state public policies that govern the relationship between solar customers and electric utility companies.