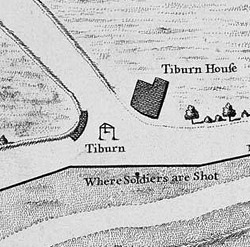

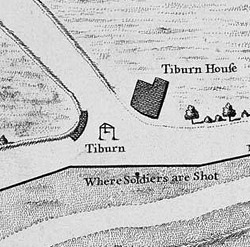

Tyburn was a manor (estate) in London, Middlesex, England, one of two which were served by the parish of Marylebone. Tyburn took its name from the Tyburn Brook, a tributary of the River Westbourne. The name Tyburn, from Teo Bourne, means 'boundary stream'.

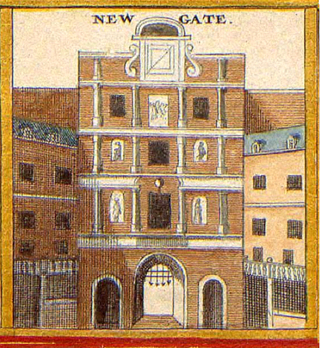

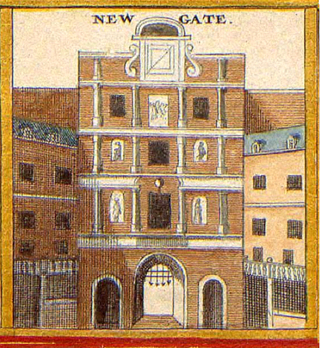

Newgate Prison was a prison at the corner of Newgate Street and Old Bailey, just inside the City of London, England, originally at the site of Newgate, a gate in the Roman London Wall. Built in the 12th century and demolished in 1904, the prison was extended and rebuilt many times, and remained in use for over 700 years, from 1188 to 1902.

Penal transportation was the relocation of convicted criminals, or other persons regarded as undesirable, to a distant place, often a colony, for a specified term; later, specifically established penal colonies became their destination. While the prisoners may have been released once the sentences were served, they generally did not have the resources to return home.

York Castle is a fortified complex in the city of York, England. It consists of a sequence of castles, prisons, law courts and other buildings, which were built over the last nine centuries on the south side of the River Foss. The now ruined keep of the medieval Norman castle is commonly referred to as Clifford's Tower. Built originally on the orders of William I to dominate the former Viking city of Jórvík, the castle suffered a tumultuous early history before developing into a major fortification with extensive water defences. After a major explosion in 1684 rendered the remaining military defences uninhabitable, York Castle continued to be used as a gaol and prison until 1929.

Newgate was one of the historic seven gates of the London Wall around the City of London and one of the six which date back to Roman times. Newgate lay on the west side of the wall and the road issuing from it headed over the River Fleet to Middlesex and western England. Beginning in the 12th century, parts of the gate buildings were used as a gaol, which later developed into Newgate Prison.

John "Jack" Sheppard, or "Honest Jack", was a notorious English thief and prison escapee of early 18th-century London.

The Old Melbourne Gaol is a former jail and current museum on Russell Street, in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. It consists of a bluestone building and courtyard, and is located next to the old City Police Watch House and City Courts buildings, and opposite the Russell Street Police Headquarters. It was first constructed starting in 1839, and during its operation as a prison between 1845 and 1924, it held and executed some of Australia's most notorious criminals, including bushranger Ned Kelly and serial killer Frederick Bailey Deeming. In total, 133 people were executed by hanging. Though it was used briefly during World War II, it formally ceased operating as a prison in 1924; with parts of the jail being incorporated into the RMIT University, and the rest becoming a museum.

William Worcester, also called William of Worcester, William Worcestre or William Botoner was an English topographer, antiquary and chronicler.

Felo de se was a concept applied against the personal estates (assets) of adults who ended their own lives. Early English common law, among others, by this concept considered suicide a crime—a person found guilty of it, though dead, would ordinarily see penalties including forfeiture of property to the monarch and a shameful burial. Beginning in the seventeenth century precedent and coroners' custom gradually deemed suicide temporary insanity—court-pronounced conviction and penalty to heirs were gradually phased out.

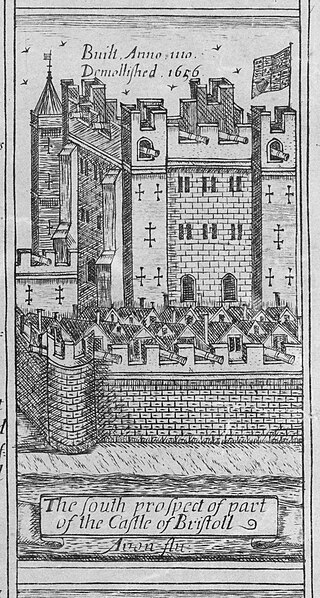

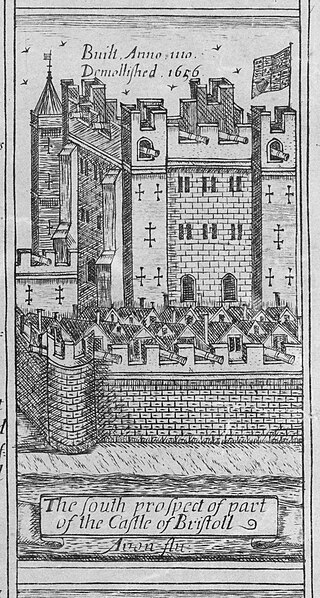

Bristol Castle was a Norman castle established in the late 11th century on the north bank of the River Avon in Bristol. Remains can be seen today in Castle Park near the Broadmead Shopping Centre, including the sally port.

The Bocardo Prison in Oxford, England existed until 1771. Its origins were medieval, and its most famous prisoners were the Protestant Oxford martyrs in 1555. Other prisoners included a number of Quakers, like Elizabeth Fletcher, among the first preachers of the Friends to come to Oxford in 1654.

Gloucester Castle was a Norman-era royal castle situated in the city of Gloucester in Gloucestershire, England. It was demolished in 1787 and replaced by Gloucester Prison.

The New Gaol is in Cumberland Road, Spike Island, Bristol, England, near Bristol Harbour.

Christmas Steps is a historic street in the city centre of Bristol, England.

Bewell's Cross was a large medieval stone cross and boundary marker on the northern edge of the County of Bristol. It was also the site of the city gallows from at least the fifteenth century till 1820. The surviving stump of the Cross was dug up in 1829.

William Calcraft was a 19th-century English hangman, one of the most prolific of British executioners. It is estimated in his 45-year career he carried out 450 executions. A cobbler by trade, Calcraft was initially recruited to flog juvenile offenders held in Newgate Prison. While selling meat pies on streets around the prison, Calcraft met the City of London's hangman, John Foxton.

The Marshalsea (1373–1842) was a notorious prison in Southwark, just south of the River Thames. Although it housed a variety of prisoners—including men accused of crimes at sea and political figures charged with sedition—it became known, in particular, for its incarceration of the poorest of London's debtors. Over half of England's prisoners in the 18th century were in jail because of debt.

Worcester Castle was a Norman fortification built between 1068 and 1069 in Worcester, England by Urse d'Abetot on behalf of William the Conqueror. The castle had a motte-and-bailey design and was located on the south side of the old Anglo-Saxon city, cutting into the grounds of Worcester Cathedral. Royal castles were owned by the king and maintained on his behalf by an appointed constable. At Worcester that role was passed down through the local Beauchamp family on a hereditary basis, giving them permanent control of the castle and considerable power within the city. The castle played an important part in the wars of the 12th and early 13th century, including the Anarchy and the First Barons' War.

The County Gaol, situated in North Parade, Monmouth, Wales, was Monmouthshire's main prison when it was opened in 1790. It served as the county jail of Monmouthshire and criminals or those who fell foul of the authorities were hanged here until the 1850s and some 3,000 people viewed the last hanging. The jail covered an area of about an acre, with a chapel, infirmary, living quarters and a treadmill. It was closed in 1869. In 1884 most of the building was demolished, and today nothing remains but the gatehouse which is a Grade II listed building. Within the gatehouse, there exists "a representation in coloured glass of the complete original buildings". It is one of 24 buildings on the Monmouth Heritage Trail.

The following is a timeline of the history of the city of Bristol, England.