The number 106 fuze was the first British instantaneous percussion artillery fuze, first tested in action in late 1916 and deployed in volume in early 1917.

The number 106 fuze was the first British instantaneous percussion artillery fuze, first tested in action in late 1916 and deployed in volume in early 1917.

Britain entered World War I with a policy of using shrapnel shells for its field guns (13-pounder and 18-pounder), intended to burst above head-height for anti-personnel use. British heavy artillery was expected to attack fortifications, requiring high-explosive shells to penetrate the target to some extent before exploding. Hence British artillery fuzes were optimised for these functions. Experiences of trench warfare on the Western front in 1914–1916 indicated that British artillery was unable to reliably destroy barbed-wire barricades, which required shells to explode instantaneously on contact with the wire or ground surface: British high-explosive shells would penetrate the ground before exploding, rendering them useless for destroying surface targets.

British No. 100 and later Nos. 101, 102 and 103 nose "graze" fuzes available in the field from August 1915 onwards [1] could explode a high-explosive shell very quickly on experiencing a major change in direction or velocity, but were not "instantaneous": there was still some delay in activation, and limited sensitivity: they could not detect contact with a frail object like barbed wire or soft ground surface. Hence they would penetrate objects or ground slightly before detonating, instead of on the ground surface as required for wire cutting. [2] These graze and impact fuzes continued to be used as intended for medium and heavy artillery high-explosive shells.

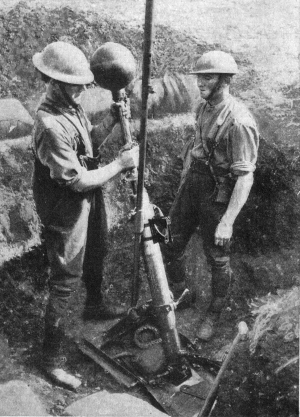

Up to and including the Battle of the Somme in 1916, British forces relied on shrapnel shells fired by 18-pounder field guns and spherical high-explosive bombs fired by 2-inch "plum-pudding" mortars for cutting barbed-wire defences. The disadvantage of shrapnel for this purpose was that it relied on extreme accuracy on setting the fuze timing to burst the shell close to the ground just in front of the wire: if the shell burst fractionally too short or too long it could not cut the wire, and also the spherical shrapnel balls were not of an optimal shape for cutting strands of wire. While the 2-inch mortar bombs cut wire effectively, their maximum range of 570 yards (520 m) limited their usefulness.

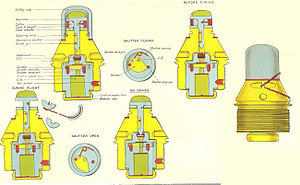

The number 106 fuze drew on French technology to provide a mechanism for reliably detonating a high-explosive shell instantaneously when the nose made physical contact with the slightest object like a strand of barbed wire or the ground surface. Hence it was a "direct action" rather than a "graze" fuze: simple deceleration or change of direction would not activate it, only direct physical contact between the hammer projecting from the nose and an external object. The basic mechanism was a steel hammer on the end of a spindle projecting forward from the nose of the fuze. The slightest movement inwards of this spindle caused the fuze to detonate and hence explode the shell before it penetrated the ground.

The steel hammer had a softer aluminium cap which absorbed the force of a glancing blow and prevented the spindle from bending or breaking, reducing the risk of misfire.

The first safety mechanism was a length of brass tape wrapped around the spindle between the fuze body and the hammer head, which prevented the spindle from moving inward. On firing, the hammer's inertia caused it to "setback" fractionally i.e. it resisted acceleration, and hence the accelerating fuze body forced the tape wrapped around the spindle against the underside of the hammer head, preventing the tape from unwinding. When acceleration ceased shortly after the shell left the gun barrel, the hammer and fuze body were travelling at the same speed and the hammer ceased to "set back", freeing the tape. The shell's rotation then caused a weight on the end of the tape to unwind the tape through centrifugal force, hence activating the fuze. Because of this, usage of this fuze in action was characterised by British troops in the front lines noticing the descending tapes detached from the fuzes as they travelled overhead towards the enemy lines.

After the tape detached during flight, the hammer was prevented from being forced inward by air resistance by a thin "shearing wire" passing through the hammer spindle, which was easily broken by the hammer encountering any physical resistance. The spindle was prevented from rotating relative to the fuze body in flight, and hence from snapping the shearing wire, by a guide pin passing through a cutout in the spindle.

Later versions (designated "E") incorporated an additional safety mechanism: an internal "shutter", also activated by rotation of the shell after firing, which closed the channel between the striker in the nose and the powder magazine in the base until it was clear of the gun which fired it. On firing, the shutter resisted acceleration ("setback") and the accelerating shell body pushed against it, preventing the shutter from moving. When acceleration ceased shortly after the shell left the gun barrel, the shutter ceased to "set back" and was free to spin outwards, activating the fuze.

The fuze was first used experimentally in action in the later phases of the Battle of the Somme in late 1916, and entered service in early 1917. [3] [4] From then onwards British forces had a reliable means of detonating high-explosive shells on the ground surface without merely digging holes as they had previously.

The chain of events necessary to allow the fuze to activate a shell were:

On the Western Front in 1917 and 1918, the No. 106 fuze was typically employed on high-explosive shells for cutting barbed wire, fired by 18-pounder field guns at short to medium range, and by Mk VII [5] and Mk XIX 6-inch field guns at long range. Its instantaneous action also made it useful for counter-battery fire: high-explosive shells fired by 60-pounder and six-inch field guns were targeted on enemy artillery, and by bursting above ground could cause maximum damage to enemy artillery, mountings and crew. It was also approved as the primary fuze for high-explosive shells for QF 4.5 inch howitzers from August 1916 onward. [4]

This fuze was also used to burst smoke shells.

There were many versions of the No. 106 and it remained in service in the form of its streamlined variant, the No. 115, until World War II.

War Office. "Chapperton Down Artillery School [film]". film.iwmcollections.org.uk. Imperial War Museum. 10:05:25:00. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during sieges, and led to heavy, fairly immobile siege engines. As technology improved, lighter, more mobile field artillery cannons developed for battlefield use. This development continues today; modern self-propelled artillery vehicles are highly mobile weapons of great versatility generally providing the largest share of an army's total firepower.

Shrapnel shells were anti-personnel artillery munitions which carried many individual bullets close to a target area and then ejected them to allow them to continue along the shell's trajectory and strike targets individually. They relied almost entirely on the shell's velocity for their lethality. The munition has been obsolete since the end of World War I for anti-personnel use; high-explosive shells superseded it for that role. The functioning and principles behind Shrapnel shells are fundamentally different from high-explosive shell fragmentation. Shrapnel is named after Lieutenant-General Henry Shrapnel (1761–1842), a British artillery officer, whose experiments, initially conducted on his own time and at his own expense, culminated in the design and development of a new type of artillery shell.

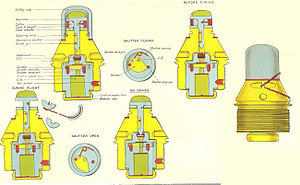

A detonator, frequently called a blasting cap, is a small sensitive device used to detonate a larger, more powerful but relatively insensitive secondary explosive of an explosive device used in commercial mining, excavation, demolition, etc.

Armour-piercing ammunition (AP) is a type of projectile designed to penetrate either body armour or vehicle armour.

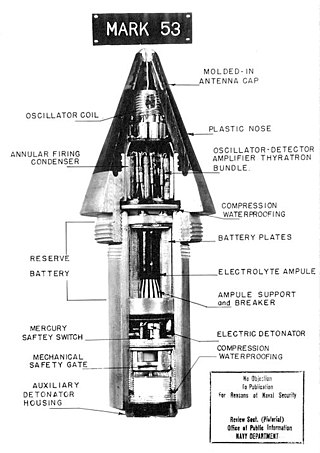

A proximity fuze is a fuze that detonates an explosive device automatically when the distance to the target becomes smaller than a predetermined value. Proximity fuzes are designed for targets such as planes, missiles, ships at sea, and ground forces. They provide a more sophisticated trigger mechanism than the common contact fuze or timed fuze. It is estimated that it increases the lethality by 5 to 10 times, compared to these other fuzes.

A shell, in a military context, is a projectile whose payload contains an explosive, incendiary, or other chemical filling. Originally it was called a bombshell, but "shell" has come to be unambiguous in a military context. Modern usage sometimes includes large solid kinetic projectiles, which are more properly termed shot. Solid shot may contain a pyrotechnic compound if a tracer or spotting charge is used.

In an explosive, pyrotechnic device, or military munition, a fuse is the part of the device that initiates function. In common usage, the word fuse is used indiscriminately. However, when being specific, the term fuse describes a simple pyrotechnic initiating device, like the cord on a firecracker whereas the term fuze is used when referring to a more sophisticated ignition device incorporating mechanical and/or electronic components, such as a proximity fuze for an M107 artillery shell, magnetic or acoustic fuze on a sea mine, spring-loaded grenade fuze, pencil detonator, or anti-handling device.

The Ordnance QF 18-pounder, or simply 18-pounder gun, was the standard British Empire field gun of the First World War-era. It formed the backbone of the Royal Field Artillery during the war, and was produced in large numbers. It was used by British Forces in all the main theatres, and by British troops in Russia in 1919. Its calibre (84 mm) and shell weight were greater than those of the equivalent field guns in French (75 mm) and German (77 mm) service. It was generally horse drawn until mechanisation in the 1930s.

An air burst or airburst is the detonation of an explosive device such as an anti-personnel artillery shell or a nuclear weapon in the air instead of on contact with the ground or target. The principal military advantage of an air burst over a ground burst is that the energy from the explosion is distributed more evenly over a wider area; however, the peak energy is lower at ground zero.

This article explains terms used for the British Armed Forces' ordnance (weapons) and ammunition. The terms may have slightly different meanings in the military of other countries.

The L118 light gun is a 105 mm towed howitzer. It was originally designed and produced in England for the British Army in the 1970s. It has since been widely exported. The L119 and the United States Army's M119 are variants that use a different type of ammunition.

The SC 250 was an air-dropped general purpose high-explosive bomb built by Germany during World War II and used extensively during that period. It could be carried by almost all German bomber aircraft, and was used to notable effect by the Junkers Ju 87 Stuka. The bomb's weight was about 250 kg, from which its designation was derived.

Fragmentation is the process by which the casing, shot, or other components of an anti-personnel weapon, bomb, barrel bomb, land mine, IED, artillery, mortar, tank gun, or autocannon shell, rocket, missile, grenade, etc. are dispersed and/or shattered by the detonation of the explosive filler.

The 2 inch medium trench mortar, also known as the 2-inch howitzer, and nicknamed the "toffee apple" or "plum pudding" mortar, was a British smooth bore muzzle loading (SBML) medium trench mortar in use in World War I from mid-1915 to mid-1917. The designation "2-inch" refers to the mortar barrel, into which only the 22-inch bomb shaft but not the bomb itself was inserted; the spherical bomb itself was actually 9 inches (230 mm) in diameter and weighed 42 lb (19 kg), hence this weapon is more comparable to a standard mortar of approximately 5-6 inch bore.

Ammunition is the material fired, scattered, dropped, or detonated from any weapon or weapon system. Ammunition is both expendable weapons and the component parts of other weapons that create the effect on a target.

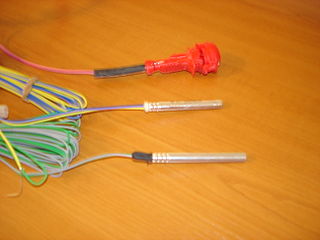

In military munitions, a fuze is the part of the device that initiates function. In some applications, such as torpedoes, a fuze may be identified by function as the exploder. The relative complexity of even the earliest fuze designs can be seen in cutaway diagrams.

A grenade is an explosive weapon typically thrown by hand, but can also refer to a shell shot from the muzzle of a rifle or a grenade launcher. A modern hand grenade generally consists of an explosive charge ("filler"), a detonator mechanism, an internal striker to trigger the detonator, and a safety lever secured by a cotter pin. The user removes the safety pin before throwing, and once the grenade leaves the hand the safety lever gets released, allowing the striker to trigger a primer that ignites a fuze, which burns down to the detonator and explodes the main charge.

An artillery fuze or fuse is the type of munition fuze used with artillery munitions, typically projectiles fired by guns, howitzers and mortars. A fuze is a device that initiates an explosive function in a munition, most commonly causing it to detonate or release its contents, when its activation conditions are met. This action typically occurs a preset time after firing, or on physical contact with or detected proximity to the ground, a structure or other target. Fuze, a variant of fuse, is the official NATO spelling.

A contact fuze, impact fuze, percussion fuze or direct-action (D.A.) fuze (UK) is the fuze that is placed in the nose of a bomb or shell so that it will detonate on contact with a hard surface.

The Panzerwurfkörper 42 was a HEAT grenade that was developed by Germany and used by the Wehrmacht during World War II. The Panzerwurfkörper 42 was designed to be fired from a Leuchtpistole or flare gun in English.