Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) are highly carcinogenic chemical compounds, formerly used in industrial and consumer products, whose production was banned in the United States by the Toxic Substances Control Act in 1976 and internationally by the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants in 2001.

Warren County is a county located in the northeastern Piedmont region of the U.S. state of North Carolina, on the northern border with Virginia, made famous for a landfill and birthplace of the environmental justice movement. As of the 2020 census, its population was 18,642. Its county seat is Warrenton. It was a center of tobacco and cotton plantations, education, and later textile mills.

Emelle is a town in Sumter County, Alabama, United States. It was named after the daughters of the man who donated the land for the town. The town was started in the 19th century but not incorporated until 1981. The daughters of the man who donated were named Emma Dial and Ella Dial, so he combined the two names to create Emelle. Emelle was famous for its great cotton. The first mayor of Emelle was James Dailey. He served two terms. The current mayor is Roy Willingham Sr. The population was 32 at the 2020 census.

A landfill site, also known as a tip, dump, rubbish dump, garbage dump, trash dump, or dumping ground, is a site for the disposal of waste materials. Landfill is the oldest and most common form of waste disposal, although the systematic burial of the waste with daily, intermediate and final covers only began in the 1940s. In the past, refuse was simply left in piles or thrown into pits; in archeology this is known as a midden.

Toxic waste is any unwanted material in all forms that can cause harm. Mostly generated by industry, consumer products like televisions, computers, and phones contain toxic chemicals that can pollute the air and contaminate soil and water. Disposing of such waste is a major public health issue.

Love Canal is a neighborhood in Niagara Falls, New York, United States, infamous as the location of a 0.28 km2 (0.11 sq mi) landfill that became the site of an enormous environmental disaster in the 1970s. Decades of dumping toxic chemicals killed residents and harmed the health of hundreds, often profoundly; the area was cleaned up over the course of 21 years in a Superfund operation.

Environmental racism, ecological racism, or ecological apartheid is a form of institutional racism leading to landfills, incinerators, and hazardous waste disposal being disproportionately placed in communities of color. Internationally, it is also associated with extractivism, which places the environmental burdens of mining, oil extraction, and industrial agriculture upon indigenous peoples and poorer nations largely inhabited by people of color.

Illegal dumping, also called fly dumping or fly tipping (UK), is the dumping of waste illegally instead of using an authorized method such as curbside collection or using an authorized rubbish dump. It is the illegal deposit of any waste onto land, including waste dumped or tipped on a site with no license to accept waste. The United States Environmental Protection Agency developed a “profile” of the typical illegal dumper. Characteristics of offenders include local residents, construction and landscaping contractors, waste removers, scrap yard operators, and automobile and tire repair shops.

Environmental justice or eco-justice, is a social movement to address environmental injustice, which occurs when poor or marginalized communities are harmed by hazardous waste, resource extraction, and other land uses from which they do not benefit. The movement has generated hundreds of studies showing that exposure to environmental harm is inequitably distributed.

In land-use planning, a locally unwanted land use (LULU) is a land use that creates externality costs on those living in close proximity. These costs include potential health hazards, poor aesthetics, or reduction in home values. LULUs often gravitate to disadvantaged areas such as slums, industrial neighborhoods and poor, minority, unincorporated or politically under-represented places that cannot fight them off. Such facilities with such hazards need to be created for the greater benefits that they offer society.

Munisport Landfill is a closed landfill located in North Miami, Florida adjacent to a low-income community, a regional campus of Florida International University, Oleta River State Park, and estuarine Biscayne Bay.

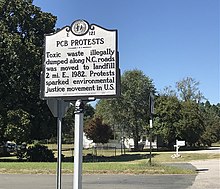

Warren County PCB Landfill was a PCB landfill located in Warren County, North Carolina, near the community of Afton south of Warrenton. The landfill was created in 1982 by the State of North Carolina as a place to dump contaminated soil as result of an illegal PCB dumping incident. The site, which is about 150 acres (0.61 km2), was extremely controversial and led to years of lawsuits. Warren County was one of the first cases of environmental justice in the United States and set a legal precedent for other environmental justice cases. The site was approximately three miles south of Warrenton. The State of North Carolina owned about 19 acres (77,000 m2) of the tract where the landfill was located, and Warren County owned the surrounding acreage around the borders.

Benjamin Franklin Chavis Jr. is an African-American activist, author, journalist, and the current president and CEO of the National Newspaper Publishers Association. He serves as national co-chair for the political organization No Labels.

The Killing Ground is a 1979 American documentary film written by Brit Hume. It was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature.

The Kettleman Hills Hazardous Waste Facility is a large hazardous waste and municipal solid waste disposal facility, operated by Waste Management, Inc. The landfill is located at 35.9624°N 120.0102°W, 3.5 mi (5.6 km) southwest of Kettleman City on State Route 41 in the western San Joaquin Valley, Kings County, California.

The Casmalia Resources Hazardous Waste Landfill was a 252–acre disposal facility located in the hills near Casmalia, California. During its operation, 4.5 billion pounds of hazardous waste from up to 10,000 individuals, businesses and government agencies were dumped on site. The facility was closed in 1989, and is now a listed as a Superfund Site by the Environmental Protection Agency.

Greenaction for Health and Environmental Justice, formed in 1997, is a multiracial grassroots organization based in San Francisco that works with low-income and working class urban, rural, and indigenous communities. It runs campaigns in the United States to build grassroots networks, and advocate for social justice.

Hazel M. Johnson was an environmental activist on the South Side of Chicago, Illinois. She is considered to be the mother of environmental justice.

Dumping in Dixie is a 1990 book by the American professor, author, activist, and environmental sociologist Robert D. Bullard. Bullard spotlights the quintessence of the economic, social, and psychological consequences induced by the siting of noxious facilities in mobilizing the African American community. Starting with the assertion that every human has the right to a healthy environment, the book documents the journey of five American communities of color as they rally to safeguard their health and homes from the lethal effects of pollution. Further, Bullard investigates the heterogeneous obstacles to social and environmental justice that African American communities often encounter. Dumping in Dixie is widely acknowledged as the first book to discuss environmental injustices and distill the concept of environmental justice holistically. Since the publication of Dumping in Dixie, Bullard has emerged as one of the seminal figures of the environmental justice movement; some even label Bullard as the "father of environmental justice".

Environmental racism is a form of institutional racism, in which people of colour bear a disproportionate burden of environmental harms, such as pollution from hazardous waste disposal and the effects of natural disasters. Environmental racism exposes Native Americans, African Americans, Asian Americans, Pacific Islanders, and Hispanic populations to physical health hazards and may negatively impact mental health. It creates disparities in many different spheres of life, such as transportation, housing, and economic opportunity.