The Troubles were an ethno-nationalist conflict in Northern Ireland that lasted for about 30 years from the late 1960s to 1998. Also known internationally as the Northern Ireland conflict, it is sometimes described as an "irregular war" or "low-level war". The conflict began in the late 1960s and is usually deemed to have ended with the Good Friday Agreement of 1998. Although the Troubles mostly took place in Northern Ireland, at times violence spilled over into parts of the Republic of Ireland, England, and mainland Europe.

Ian Richard Kyle Paisley, Baron Bannside, was a loyalist politician and Protestant religious leader from Northern Ireland who served as leader of the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) from 1971 to 2008 and First Minister of Northern Ireland from 2007 to 2008.

John Hume was an Irish nationalist politician in Northern Ireland and a Nobel Peace Prize laureate. A founder and leader of the Social Democratic and Labour Party, Hume served in the Northern Ireland Parliament; the Northern Ireland Assembly including, in 1974, its first power-sharing executive; the European Parliament and the United Kingdom Parliament. Seeking an accommodation between Irish nationalism and Ulster unionism, and soliciting American support, he was both critical of British government policy in Northern Ireland and opposed to the republican embrace of "armed struggle". In their 1998 citation, the Norwegian Nobel Committee recognised Hume as an architect of the Good Friday Agreement. For himself, Hume wished to be remembered as having been, in his earlier years, a pioneer of the credit union movement.

The Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) is a unionist, loyalist, British nationalist and national conservative political party in Northern Ireland. It was founded in 1971 during the Troubles by Ian Paisley, who led the party for the next 37 years. It is currently led by Gavin Robinson, who initially stepped in as an interim after the resignation of Jeffrey Donaldson. It is the second largest party in the Northern Ireland Assembly, and was the fifth-largest party in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom prior to its dissolution. The party has been described as centre-right to right-wing and socially conservative, being anti-abortion and opposing same-sex marriage. The DUP sees itself as defending Britishness and Ulster Protestant culture against Irish nationalism and republicanism. It is also Eurosceptic and supported Brexit.

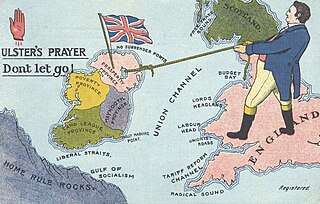

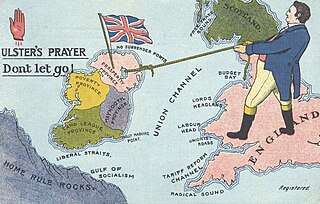

Unionism in Ireland is a political tradition that professes loyalty to the crown of the United Kingdom and to the union it represents with England, Scotland and Wales. The overwhelming sentiment of Ireland's Protestant minority, unionism mobilised in the decades following Catholic Emancipation in 1829 to oppose restoration of a separate Irish parliament. Since Partition in 1921, as Ulster unionism its goal has been to retain Northern Ireland as a devolved region within the United Kingdom and to resist the prospect of an all-Ireland republic. Within the framework of the 1998 Belfast Agreement, which concluded three decades of political violence, unionists have shared office with Irish nationalists in a reformed Northern Ireland Assembly. As of February 2024, they no longer do so as the larger faction: they serve in an executive with an Irish republican First Minister.

The Ulster Democratic Party (UDP) was a small loyalist political party in Northern Ireland. It was established in June 1981 as the Ulster Loyalist Democratic Party by the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), to replace the New Ulster Political Research Group. The UDP name had previously been used in the 1930s by an unrelated party, which on one occasion contested Belfast Central.

The Sunningdale Agreement was an attempt to establish a power-sharing Northern Ireland Executive and a cross-border Council of Ireland. The agreement was signed by the British and Irish governments at Northcote House in Sunningdale Park, located in Sunningdale, Berkshire, on 9 December 1973. Unionist opposition, violence and a general strike caused the collapse of the agreement in May 1974.

Local government in Northern Ireland is divided among 11 districts. Councils in Northern Ireland do not carry out the same range of functions as those in the rest of the United Kingdom; for example they have no responsibility for education, road-building or housing. Their functions include planning, waste and recycling services, leisure and community services, building control and local economic and cultural development. The collection of rates is handled centrally by the Land and Property Services agency of the Northern Ireland Executive.

Derry City Council was the local government authority for the city of Derry in Northern Ireland. It merged with Strabane District Council in April 2015 under local government reorganisation to become Derry and Strabane District Council.

Free Derry was a self-declared autonomous Irish nationalist area of Derry, Northern Ireland that existed between 1969 and 1972 during the Troubles. It emerged during the Northern Ireland civil rights movement, which sought to end discrimination against the Irish Catholic/nationalist minority by the Protestant/unionist government. The civil rights movement highlighted the sectarianism and police brutality of the overwhelmingly Protestant police force, the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC).

The Ulster Constitution Defence Committee (UCDC) was established in Northern Ireland in April 1966 as the governing body of the loyalist Ulster Protestant Volunteers (UPV). It coordinated parades, counter-demonstrations, and paramilitary activities to maintain the status quo of the government, led a campaign against the reforms of Terence O'Neill and stymied the civil rights movement.

The Battle of the Bogside was a large three-day riot that took place from 12 to 14 August 1969 in Derry, Northern Ireland. Thousands of Catholic/Irish nationalist residents of the Bogside district, organised under the Derry Citizens' Defence Association, clashed with the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and loyalists. It sparked widespread violence elsewhere in Northern Ireland, led to the deployment of British troops, and is often seen as the beginning of the thirty-year conflict known as the Troubles.

The Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA) (Irish: Cumann Cearta Sibhialta Thuaisceart Éireann) was an organisation that campaigned for civil rights in Northern Ireland during the late 1960s and early 1970s. Formed in Belfast on 9 April 1967, the civil rights campaign attempted to achieve reform by publicising, documenting, and lobbying for an end to discrimination against Catholics in areas such as elections (which were subject to gerrymandering and property requirements), discrimination in employment, in public housing and abuses of the Special Powers Act.

The Ulster Workers' Council (UWC) strike was a general strike that took place in Northern Ireland between 15 May and 28 May 1974, during "the Troubles". The strike was called by unionists who were against the Sunningdale Agreement, which had been signed in December 1973. Specifically, the strikers opposed the sharing of political power with Irish nationalists, and the proposed role for the Republic of Ireland's government in running Northern Ireland.

Rathcoole is a housing estate in Newtownabbey, County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It was built in the 1950s to house many of those displaced by the demolition of inner city housing in Belfast city. Rathcoole is within the wider Antrim and Newtownabbey Borough. Its approximate borders are provided by O'Neill Road on the north, Doagh Road on the east, Shore Road on the south and Church Road and Merville Garden Village on the west.

The Derry Housing Action Committee (DHAC), was an organisation formed in 1968 in Derry, Northern Ireland to protest about housing conditions and provision.

Events during the year 1968 in Northern Ireland.

Parades are a prominent cultural feature of Northern Ireland. The overwhelming majority of parades are held by Ulster Protestant, unionist or Ulster loyalist groups, but some Irish nationalist, republican and non-political groups also parade. Due to longstanding controversy surrounding the contentious nature of some parades, a quasi-judicial public body — the Parades Commission — exists to place conditions and settle disputes. Although not all parading groups recognise the Commission's authority, its decisions are legally binding.

Clarawood is a housing estate in Belfast, Northern Ireland. It is located in the east of the city and incorporates the neighbouring Richhill development. Its name is probably derived from An Chlárach. It is located off Knock Road (A55).

The Northern Ireland Housing Trust was a public authority which provided public housing in Northern Ireland from 1945 until 1971, when its functions were merged into the newly created Northern Ireland Housing Executive.