Nuclear hedging

Nuclear latency can be achieved with solely peaceful intentions, but in some cases nuclear latency is achieved in order to be able to create nuclear arms in the future, which is known as "nuclear hedging". [2] While states engaging in nuclear hedging do not directly violate the NPT, they do run the risk of potentially encouraging their neighboring states, particularly those they have had conflicts with, to do the same, spawning a "virtual" arms race to ensure the potential of future nuclear capability. [2] Such a situation could rapidly escalate into an actual arms race, drastically raising tensions in the region and increasing the risk of a potential nuclear exchange. [2]

Nuclear-threshold states

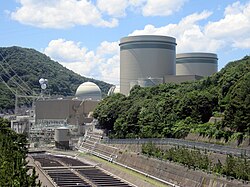

Japan is considered a "paranuclear" state, with complete technical prowess to develop a nuclear weapon quickly, [3] [4] and is sometimes called being "one screwdriver's turn" from the bomb, as it is considered to have the materials and technical capacity to make a nuclear weapon at will. [5] [6] [7] [8] [9] [10]

Iran is also considered a nuclear threshold state, [11] [12] [13] [14] and has been described being "a hop, skip, and a jump away" from developing nuclear weapons, [15] [16] [17] with its advanced nuclear program capable of producing fissile material for a bomb in a matter of days if weaponized. [18] [19] [20] Other nuclear threshold states are Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, and Brazil. [21] [22] [23]

South Africa has successfully developed its own nuclear weapons, but dismantled them in 1989. Taiwan and South Korea have both been identified as "insecure" nuclear threshold states—states with the technical capability to develop nuclear weapons. South Korea had been involved in nuclear energy technology since the end of the Korean War, and possessed an active nuclear weapons program that was terminated in the mid-1970s with its signing of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, while still engaging in some clandestine nuclear weapons research into the late 1980s, and the security motivations to seriously contemplate such an option—since the publishing of a Mitre Corporation report in 1977. [24] [25] [26] In the late 1970s the US intelligence community believed Taiwan had designed devices suitable for nuclear testing. [27]

The number of states that are technically nuclear-latent has steadily increased as nuclear energy and its requisite technologies have become more available, but the number of states that are actually at the threshold status is limited. [28] [29] Nuclear latency does not presume any particular intentions on the part of a state recognized as being nuclear-latent. [29]

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.