Universal jurisdiction is a legal principle that allows states or international organizations to claim criminal jurisdiction over an accused person regardless of where the alleged crime was committed, and regardless of the accused's nationality, country of residence, or any other relation to the prosecuting entity. Crimes prosecuted under universal jurisdiction are considered crimes against all, too serious to tolerate jurisdictional arbitrage.

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (CPPCG), or Genocide Convention, is an international treaty that criminalizes genocide and obligates state parties to enforce its prohibition. It was the first legal instrument to codify genocide as a crime, and the first human rights treaty unanimously adopted by the United Nations General Assembly, on 9 December 1948. The Convention entered into force on 12 January 1951 and has 152 state parties.

An ex post facto law is a law that retroactively changes the legal consequences of actions that were committed, or relationships that existed, before the enactment of the law. In criminal law, it may criminalize actions that were legal when committed; it may aggravate a crime by bringing it into a more severe category than it was in when it was committed; it may change the punishment prescribed for a crime, as by adding new penalties or extending sentences; or it may alter the rules of evidence in order to make conviction for a crime likelier than it would have been when the deed was committed.

Blasphemous libel was originally an offence under the common law of England. Today, it is an offence under the common law of Northern Ireland, but has been abolished in England and Wales, and repealed in Canada and New Zealand. It consists of the publication of material which exposes the Christian religion to scurrility, vilification, ridicule, and contempt, with material that must have the tendency to shock and outrage the feelings of Christians. It is a form of criminal libel.

The Bosnian genocide refers to either the Srebrenica massacre or the wider crimes against humanity and ethnic cleansing campaign throughout areas controlled by the Army of Republika Srpska (VRS) during the Bosnian War of 1992–1995. The events in Srebrenica in 1995 included the killing of more than 8,000 Bosniak men and boys, as well as the mass expulsion of another 25,000–30,000 Bosniak civilians by VRS units under the command of General Ratko Mladić.

Dietrich v The Queen (Dietrich) was a 1992 decision of the High Court of Australia, which established a de facto constitutional requirement that legal aid be provided to defendants in serious criminal trials. The Court ruled adjournments should be granted on an indefinite basis in serious criminal trials where an accused is unrepresented "through no fault of their own", known as the "fair trial principle" and commonly referred to as the Dietrich principle. Prior to Dietrich it was customary in Australia to force to trial a person who could not afford legal representation.

Australian sedition law was an area of the criminal law of Australia relating to the crime of sedition.

Canada (AG) v Lavell, [1974] S.C.R. 1349, was a landmark 5–4 Supreme Court of Canada decision holding that Section 12(1)(b) of the Indian Act did not violate the respondents' right to "equality before the law" under Section 1 (b) of the Canadian Bill of Rights. The two respondents, Lavell and Bédard, had alleged that the impugned section was discriminatory under the Canadian Bill of Rights by virtue of the fact that it deprived Indian women of their status for marrying a non-Indian, but not Indian men.

Philippe Joseph Sands, QC is a British and French lawyer at Matrix Chambers, and Professor of Laws and Director of the Centre on International Courts and Tribunals at University College London. A specialist in international law, he appears as counsel and advocate before many international courts and tribunals, including the International Court of Justice, the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea, the European Court of Justice, the European Court of Human Rights and the International Criminal Court.

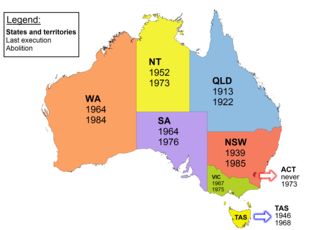

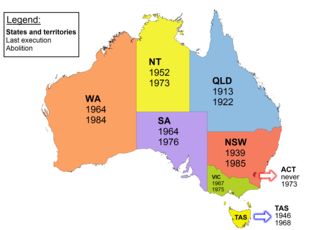

Capital punishment in Australia was a form of punishment in Australia that has been abolished in all jurisdictions. Queensland abolished the death penalty in 1922. Tasmania did the same in 1968. The Commonwealth abolished the death penalty in 1973, with application also in the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory. Victoria did so in 1975, South Australia in 1976, and Western Australia in 1984. New South Wales abolished the death penalty for murder in 1955, and for all crimes in 1985. In 2010, the Commonwealth Parliament passed legislation prohibiting the re-establishment of capital punishment by any state or territory. Australian law prohibits the extradition or deportation of a prisoner to another jurisdiction if they could be sentenced to death for any crime.

Thoburn v Sunderland City Council is a UK constitutional and administrative law case, concerning the interaction of EU law and an Act of Parliament. It is important for its recognition of the supremacy of EU law and the basis for that recognition. Though the earlier Factortame had also referred to Parliament's voluntary acceptance of the supremacy of EU law, Thoburn put less stress on the jurisprudence of the ECJ and more on the domestic acceptance of such supremacy; Lord Justice Laws suggested there was a hierarchy of "constitutional statutes" that Parliament could only expressly repeal, and so were immune from implied repeal.

Kevin Buzzacott, often referred to as Uncle Kev as an Aboriginal elder, is an Indigenous Australian from the Arabunna nation in northern South Australia. He has campaigned widely for cultural recognition, justice and land rights for Aboriginal people, and has initiated and led numerous campaigns including against uranium mining at Olympic Dam, South Australia on Kokatha land, and the exploitation of the water from the Great Artesian Basin.

Sixteen European countries and Israel have laws against Holocaust denial, the denial of the systematic genocidal killing of approximately six million Jews in Europe by Nazi Germany in the 1930s and 1940s. Many countries also have broader laws that criminalize genocide denial. Among the countries that ban Holocaust denial, Austria, Germany, Hungary, Poland and Romania also ban other elements associated with Nazism, such as the display of Nazi symbols.

National Coalition for Gay and Lesbian Equality and Another v Minister of Justice and Others is a decision of the Constitutional Court of South Africa which struck down the laws prohibiting consensual sexual activities between men. Basing its decision on the Bill of Rights in the Constitution – and in particular its explicit prohibition of discrimination based on sexual orientation – the court unanimously ruled that the crime of sodomy, as well as various other related provisions of the criminal law, were unconstitutional and therefore invalid.

The hate speech laws in Australia give redress to someone who is the victim of discrimination, vilification, or injury on grounds that differ from one jurisdiction to another. All Australian jurisdictions give redress when a person is victimised on account of colour, ethnicity, national origin, or race. Some jurisdictions give redress when a person is victimised on account of colour, ethnic origin, religion, disability, gender identity, HIV/AIDS status or sexual orientation.

Nauruan law, since Nauru's independence from Australia in 1968, is derived primarily from English and Australian common law, though it also integrates indigenous customary law to a limited extent. Nauruan common law is founded mainly on statute law enacted by the Parliament of Nauru, and on precedents set by judicial interpretations of statutes, customs and prior precedents.

In Malawi a system of Traditional Courts has been used for much of the twentieth century to mediate civil disputes and to prosecute crimes, although for much of the colonial period, their criminal jurisdiction was limited. From 1970, Regional Traditional Courts were created and given jurisdiction over virtually all criminal trials involving Africans of Malawian descent, and any appeals were directed to a National Traditional Court of Appeal rather than the Malawi High Court and from there to the Supreme Court of Appeal, as had been the case with the Local Courts before 1970.

The Law of Tuvalu comprises the legislation voted into law by the Parliament of Tuvalu and statutory instruments that become law; certain Acts passed by the Parliament of the United Kingdom ; the common law; and customary law. The land tenure system is largely based on kaitasi.

The Cannabis Act (C-45) of June, 2018 paved the way to the legalization of cannabis in Canada on October 17, 2018. Police and prosecution services in all Canadian jurisdictions are currently capable of pursuing criminal charges for cannabis marketing without a licence issued by Health Canada. The Supreme Court of Canada has held that the federal Parliament has the power to criminalise the possession of cannabis and that doing so does not infringe the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms. The Ontario Court of Appeal and the Superior Court of Ontario have, however, held that the absence of a statutory provision for medical marijuana is unconstitutional, and to that extent the federal law is of no force and/or effect if a prescription is obtained. The recreational use of cannabis has been legalized by the federal government, and took effect on October 17, 2018.

The Counter-Terrorism Legislation Act 2021 is an Act of Parliament in New Zealand which strengthens counter-terrorism laws, including a provision makes the planning of a terrorist attack a criminal offense. It was fast-tracked through Parliament due to the 2021 Auckland supermarket stabbing. The bill is supported by the Labour and National parties but opposed by the ACT, Green, and Māori parties. The bill received royal assent on 4 October 2021.