The Albanian National Awakening, commonly known as the Albanian Renaissance or Albanian Revival, is a period throughout the 19th and 20th century of a cultural, political, and social movement in the Albanian history where the Albanian people gathered strength to establish an independent cultural and political life, as well as the country of Albania.

Naim bey Frashëri, more commonly Naim Frashëri, was an Albanian historian, journalist, poet, rilindas and translator who was proclaimed as the national poet of Albania. He is regarded as a pioneer of modern Albanian literature and one of the most influential Albanian cultural icons of the 19th century.

The League of Prizren, officially the League for the Defense of the Rights of the Albanian Nation, was an Albanian political organization that was officially founded on June 10, 1878 in the old town of Prizren in the Kosovo Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire. It was suppressed in April 1881.

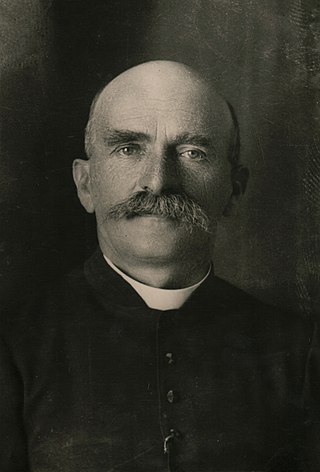

Ndre Mjeda was an Albanian philologist, poet, priest, rilindas, translator and writer of the Albanian Renaissance. He was a member of the Mjeda family.

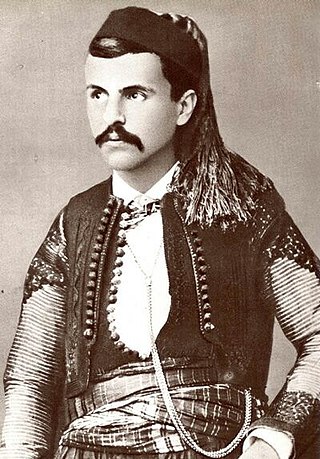

Bajram Curri was an Albanian chieftain, politician and activist who struggled for the independence of Albania, later struggling for Kosovo's incorporation into it following the 1913 Treaty of London. He was posthumously given the title Hero of Albania.

Filip Shiroka was a classical Rilindja poet.

The Autocephalous Orthodox Church of Albania, commonly known as the Albanian Orthodox Church or the Orthodox Church of Albania, is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox church. It declared its autocephaly in 1922 through its Congress of 1922, and gained recognition from the Patriarch of Constantinople in 1937.

Sami bey Frashëri or Şemseddin Sâmi was an Ottoman Albanian writer, lexicographer, philosopher, playwright and a prominent figure of the Rilindja Kombëtare, the National Renaissance movement of Albania, together with his two brothers Abdyl and Naim. He also supported Turkish nationalism against its Ottoman counterpart, along with secularism against theocracy.

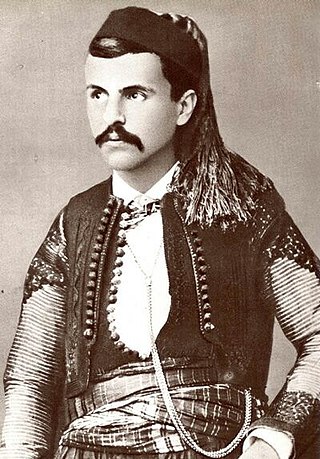

Pashko Vasa, known as Vaso Pasha or Wassa Pasha, was an Albanian writer, poet and publicist of the Albanian National Awakening, and Ottoman mutasarrif of Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate from 1882 until his death.

Albanian nationalism is a general grouping of nationalist ideas and concepts generated by ethnic Albanians that were first formed in the 19th century during the Albanian National Awakening. Albanian nationalism is also associated with similar concepts, such as Albanianism ("Shqiptaria") and Pan-Albanianism, that includes ideas on the creation of a geographically expanded Albanian state or a Greater Albania encompassing adjacent Balkan lands with substantial Albanian populations.

Jani Vreto was an Albanian writer, printer, publisher and important figure of the Albanian National Awakening. He was responsible for setting up and overseeing the work of the first Albanian printing house in Bucharest in 1886.

Hoxhë Hasan Tahsini or simply Hoxha Tahsim was an Albanian alim, astronomer, mathematician and philosopher. He was the first rector of Istanbul University and one of the founders of the Central Committee for Defending Albanian Rights. Tahsini is regarded as one of the most prominent scholars of the Ottoman Empire of the 19th century.

Prenk Bib Doda, also known as Prênk Pasha, was an Albanian member of the Young Turks, prince of Mirdita, and politician in the Principality of Albania.

Irreligion, atheism and agnosticism are present among Albanians, along with the predominant faiths of Islam and Christianity. The majority of Albanians lead a secular life and reject religious considerations to shape or condition their way of life.

Shoshi is a historical Albanian tribe (fis) and region of northern Albania in the lower Shala valley. Shoshi is first recorded as a small settlement in 1485. The fis itself traces its origin to the brothers Gjol and Pep Suma. The community of their descendants gradually grew to control part of the Dukagjin highlands. In the 19th century Shoshi also became a bajrak.

The Islamization of Albania occurred as a result of the Ottoman conquest of the region beginning in 1385. The Ottomans through their administration and military brought Islam to Albania.

Albanian nationalism in Albania emerged during the 19th century. The onset of the Great Eastern Crisis (1870s) that threatened partition of Balkan Albanian inhabited lands by neighbouring Orthodox Christian states stimulated the emergence of the Albanian national awakening (Rilindja) and nationalist movement. During the 19th century, some Western scholarly influences, Albanian diasporas such as the Arbëreshë and Albanian National Awakening figures contributed greatly to spreading influences and ideas among Balkan Albanians within the context of Albanian self-determination. Among those were ideas of an Illyrian contribution to Albanian ethnogenesis which still dominate Albanian nationalism in contemporary times and other ancient peoples claimed as ancestors of the Albanians, in particular the Pelasgians of which have been claimed again in recent times.

Albania has been a secular state since its founding in 1912, despite various changes in political systems. During the 20th century after Independence (1912) the democratic, monarchic and later the totalitarian communist regimes followed a systematic secularisation of the nation and the national culture. Albanians have historically been a particular case and a unique symbol of religious harmony and tolerance in the Balkans. Muslims, Catholic and Orthdox Christians have always lived in harmony and coexisted without divisive religious confrontations.

The Taksim meeting alternatively known as the Taksim Plot and less commonly as the Taksim Assembly was a secret meeting held in January 1912 by Albanian nationalist deputies of the Ottoman parliament and other prominent Albanian political figures. The event gets its name from Taksim Square because of the location of the house where it was held. The meeting was organized on the initiative of Hasan Prishtina and Ismail Qemali, Albanian politicians, who invited most of the MPs of Albanian origin and aimed at launching an armed general uprising in Albanian territories against the central government headed by the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP). The meeting followed two other Albanian uprisings of 1910 in the Vilayet of Kosovo and 1911 in the mountains of upper Shkodra. The Taksim meeting resulted in an uprising the same year, with armed uprisings in Shkodër, Lezhë, Mirditë, Krujë and other Albanian provinces, which exceeded the organizers' expectations. The biggest uprising was in Kosovo, where the rebels were more organized and managed to take over important cities like Prizren, Peja, Gjakova, Mitrovica and others.

The Battle of Slivova was fought between the Albanian League of Prizren and the Ottoman Empire in the vicinities of the villages of Slivovë and Koshare near modern-day Ferizaj, Kosovo, between 16 and 20 April 1881.