| Oakwell Engineering Ltd v Enernorth Industries Inc | |

|---|---|

| |

| Court | Court of Appeal for Ontario |

| Full case name | Oakwell Engineering Limited v Enernorth Industries Inc. (formerly known as Energy Power Systems Limited, Engineering Power Systems Group Inc. and Engineering Power Systems Limited respectively) |

| Decided | June 9, 2006 |

| Citation(s) | Docket No. C43898, 2006 CanLII 19327 |

| Case history | |

| Appealed from | Oakwell Engineering Limited v. Enernorth Industries Inc. 2005 CanLII 27149, Court File Nos. 04-CV-271121CM3 & 04-CV-274860CM2, (2005) 76 O.R. (3d) 528, Superior Ct. (Ontario). |

| Subsequent action(s) | Enernorth Industries Inc. v. Oakwell Engineering Limited 2007 CanLII 1145, S.C. (Canada). |

| Court membership | |

| Judges sitting | Laskin, MacFarland and LaForme JJ.A. |

| Case opinions | |

| Decision by | MacFarland J.A. |

Oakwell Engineering Ltd v Enernorth Industries Inc was an appeal to the Court of Appeal for Ontario by Enernorth Industries Inc. (Enernorth), a Canadian company, from a judgment of the Ontario Superior Court of Justice granting an application brought by Oakwell Engineering Limited (Oakwell), a Singaporean company, for an order recognizing and enforcing in Ontario a judgment granted against Enernorth by the High Court of Singapore on October 16, 2003 and affirmed by the Court of Appeal of Singapore on April 27, 2004.

The Court of Appeal for Ontario is an appellate court in Ontario that is based at historic Osgoode Hall in downtown Toronto.

The Superior Court of Justice is a superior court in Ontario. The Court sits in 52 locations across the province, including 17 Family Court locations, and consists of over 300 federally appointed judges.

The Court of Appeal of the Republic of Singapore is the nation's highest court and its court of final appeal. It is the upper division of the Supreme Court of Singapore, the lower being the High Court. The Court of Appeal consists of the Chief Justice of Singapore, who is the President of the Court, and the Judges of Appeal. The Chief Justice may ask judges of the High Court to sit as members of the Court of Appeal to hear particular cases. The seat of the Court of Appeal is the Supreme Court Building.

Contents

- History of case

- Court cases in Singapore

- Court cases in Canada

- Superior Court of Ontario

- Ontario Court of Appeal

- Canadian Supreme Court

- Notes

- References

- Further reading

The case is notable because Enernorth claimed that the Singapore judgment should not be recognized in Canada because judicial standards in Singapore were not the same as those in Canada. Among other things, Enernorth alleged that links between the judiciary, business and the executive arm in Singapore suggested a real risk of bias. [1]

Judicial independence is protected by Singapore's Constitution, statutes such as the State Courts Act and Supreme Court of Judicature Act, and the common law. Independence of the judiciary is the principle that the judiciary should be separated from legislative and executive power, and shielded from inappropriate pressure from these branches of government, and from private or partisan interests. It is crucial as it serves as a foundation for the rule of law and democracy.

According to analyst Michael Backman, if Enernorth's appeal to the Ontario Court of Appeal had succeeded, this might have had the effect of dissuading companies from using Singaporean law for arbitration and trial, and calling into question the fairness of the Singaporean legal system. [2] However, Enernorth lost its appeal before the Court of Appeal, and was refused leave to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada.

Michael Backman is an Australian-born writer who now resides in London. Much of his writing relates to Asia's economies, business, culture and politics.

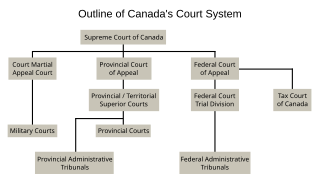

The Supreme Court of Canada is the highest court of Canada, the final court of appeals in the Canadian justice system. The court grants permission to between 40 and 75 litigants each year to appeal decisions rendered by provincial, territorial and federal appellate courts. Its decisions are the ultimate expression and application of Canadian law and binding upon all lower courts of Canada, except to the extent that they are overridden or otherwise made ineffective by an Act of Parliament or the Act of a provincial legislative assembly pursuant to section 33 of the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.