Related Research Articles

The Holocene is the current geological epoch. It began approximately 11,650 cal years before present, after the last glacial period, which concluded with the Holocene glacial retreat. The Holocene and the preceding Pleistocene together form the Quaternary period. The Holocene has been identified with the current warm period, known as MIS 1. It is considered by some to be an interglacial period within the Pleistocene Epoch, called the Flandrian interglacial.

An ice age is a long period of reduction in the temperature of Earth's surface and atmosphere, resulting in the presence or expansion of continental and polar ice sheets and alpine glaciers. Earth's climate alternates between ice ages and greenhouse periods, during which there are no glaciers on the planet. Earth is currently in the Quaternary glaciation. Individual pulses of cold climate within an ice age are termed glacial periods, and intermittent warm periods within an ice age are called interglacials or interstadials.

The Pleistocene is the geological epoch that lasted from about 2,580,000 to 11,700 years ago, spanning the earth’s most recent period of repeated glaciations. Before a change finally confirmed in 2009 by the International Union of Geological Sciences, the cutoff of the Pleistocene and the preceding Pliocene was regarded as being 1.806 million years Before Present (BP). Publications from earlier years may use either definition of the period. The end of the Pleistocene corresponds with the end of the last glacial period and also with the end of the Paleolithic age used in archaeology. The name is a combination of Ancient Greek πλεῖστος and καινός (kainós, "new".

The Snowball Earth hypothesis proposes that during one or more of Earth's icehouse climates, Earth's surface became entirely or nearly entirely frozen, sometime earlier than 650 Mya during the Cryogenian period. Proponents of the hypothesis argue that it best explains sedimentary deposits generally regarded as of glacial origin at tropical palaeolatitudes and other enigmatic features in the geological record. Opponents of the hypothesis contest the implications of the geological evidence for global glaciation and the geophysical feasibility of an ice- or slush-covered ocean and emphasize the difficulty of escaping an all-frozen condition. A number of unanswered questions remain, including whether Earth was a full snowball, or a "slushball" with a thin equatorial band of open water.

Climate variability includes all the variations in the climate that last longer than individual weather events, whereas the term climate change only refers to those variations that persist for a longer period of time, typically decades or more. In addition to the general meaning in which "climate change" may refer to any time in Earth's history, the term is commonly used to describe the current climate change now underway. In the time since the Industrial Revolution, the climate has increasingly been affected by human activities that are causing global warming and climate change.

The Younger Dryas was a return to glacial conditions after the Late Glacial Interstadial, which temporarily reversed the gradual climatic warming after the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) started receding around 20,000 BP. It is named after an indicator genus, the alpine-tundra wildflower Dryas octopetala, as its leaves are occasionally abundant in late glacial, often minerogenic-rich sediments, such as the lake sediments of Scandinavia.

A raised beach, coastal terrace, or perched coastline is a relatively flat, horizontal or gently inclined surface of marine origin, mostly an old abrasion platform which has been lifted out of the sphere of wave activity. Thus, it lies above or under the current sea level, depending on the time of its formation. It is bounded by a steeper ascending slope on the landward side and a steeper descending slope on the seaward side. Due to its generally flat shape it is often used for anthropogenic structures such as settlements and infrastructure.

The Last Glacial Period (LGP) occurred from the end of the Eemian to the end of the Younger Dryas, encompassing the period c. 115,000 – c. 11,700 years ago. The LGP is part of a larger sequence of glacial and interglacial periods known as the Quaternary glaciation which started around 2,588,000 years ago and is ongoing. The definition of the Quaternary as beginning 2.58 million years ago (Mya) is based on the formation of the Arctic ice cap. The Antarctic ice sheet began to form earlier, at about 34 Mya, in the mid-Cenozoic. The term Late Cenozoic Ice Age is used to include this early phase.

Post-glacial rebound is the rise of land masses after the removal of the huge weight of ice sheets during the last glacial period, which had caused isostatic depression. Post-glacial rebound and isostatic depression are phases of glacial isostasy, the deformation of the Earth's crust in response to changes in ice mass distribution. The direct raising effects of post-glacial rebound are readily apparent in parts of Northern Eurasia, Northern America, Patagonia, and Antarctica. However, through the processes of ocean siphoning and continental levering, the effects of post-glacial rebound on sea level are felt globally far from the locations of current and former ice sheets.

The Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), also referred to as the Late Glacial Maximum, was the most recent time during the Last Glacial Period that ice sheets were at their greatest extent. Ice sheets covered much of North America, Northern Europe, and Asia and profoundly affected Earth's climate by causing drought, desertification, and a large drop in sea levels. According to Clark et al., growth of ice sheets commenced 33,000 years ago and maximum coverage was between 26,500 years and 19–20,000 years ago, when deglaciation commenced in the Northern Hemisphere, causing an abrupt rise in sea level. Decline of the West Antarctica ice sheet occurred between 14,000 and 15,000 years ago, consistent with evidence for another abrupt rise in the sea level about 14,500 years ago.

The Black Sea deluge is the best known of three hypothetical flood scenarios proposed for the Late Quaternary history of the Black Sea. It is one of the two of these flood scenarios which propose a rapid, even catastrophic, rise in sea level of the Black Sea during the Late Quaternary.

The Mastogloia Sea is one of the prehistoric stages of the Baltic Sea in its development after the last ice age. This took place c. 8000 years ago following the Ancylus Lake stage and preceding the Littorina Sea stage.

Meltwater pulse 1A (MWP1a) is the name used by Quaternary geologists, paleoclimatologists, and oceanographers for a period of rapid post-glacial sea level rise, between 13,500 and 14,700 years ago, during which global sea level rose between 16 meters (52 ft) and 25 meters (82 ft) in about 400–500 years, giving mean rates of roughly 40–60 mm (0.13–0.20 ft)/yr. Meltwater pulse 1A is also known as catastrophic rise event 1 (CRE1) in the Caribbean Sea. The rates of sea level rise associated with meltwater pulse 1A are the highest known rates of post-glacial, eustatic sea level rise. Meltwater pulse 1A is also the most widely recognized and least disputed of the named, postglacial meltwater pulses. Other named, postglacial meltwater pulses are known most commonly as meltwater pulse 1A0, meltwater pulse 1B, meltwater pulse 1C, meltwater pulse 1D, and meltwater pulse 2. It and these other periods of rapid sea level rise are known as meltwater pulses because the inferred cause of them was the rapid release of meltwater into the oceans from the collapse of continental ice sheets.

In climatology, the 8.2-kiloyear event was a sudden decrease in global temperatures that occurred approximately 8,200 years before the present, or c. 6,200 BC, and which lasted for the next two to four centuries. It defines the start of the Northgrippian age in the Holocene epoch. Milder than the Younger Dryas cold spell before it but more severe than the Little Ice Age after it, the 8.2-kiloyear cooling was a significant exception to general trends of the Holocene climatic optimum. During the event, atmospheric methane concentration decreased by 80 ppb, an emission reduction of 15%, by cooling and drying at a hemispheric scale.

Weichselian glaciation refers to the last glacial period and its associated glaciation in northern parts of Europe. In the Alpine region it corresponds to the Würm glaciation. It was characterized by a large ice sheet that spread out from the Scandinavian Mountains and extended as far as the east coast of Schleswig-Holstein, the March of Brandenburg and Northwest Russia.

Climate change causes a variety of physical impacts on the climate system. The physical impacts of climate change foremost include globally rising temperatures of the lower atmosphere, the land, and oceans. Temperature rise is not uniform, with land masses and the Arctic region warming faster than the global average. Effects on weather encompass increased heavy precipitation, reduced amounts of cold days, increase in heat waves and various effects on tropical cyclones. The enhanced greenhouse effect causes the higher part of the atmosphere, the stratosphere, to cool. Geochemical cycles are also impacted, with absorption of CO

2 causing ocean acidification, and rising ocean water decreasing the ocean's ability to absorb further carbon dioxide. Annual snow cover has decreased, sea ice is declining and widespread melting of glaciers is underway. Thermal expansion and glacial retreat cause sea levels to increase. Retreat of ice mass may impact various geological processes as well, such as volcanism and earthquakes. Increased temperatures and other human interference with the climate system can lead to tipping points to be crossed such as the collapse of the thermohaline circulation or the Amazon rainforest. Some of these physical impacts also affect social and economic systems.

Deglaciation describes the transition from full glacial conditions during ice ages, to warm interglacials, characterized by global warming and sea level rise due to change in continental ice volume. Thus, it refers to the retreat of a glacier, an ice sheet or frozen surface layer, and the resulting exposure of the Earth's surface. The decline of the cryosphere due to ablation can occur on any scale from global to localized to a particular glacier. After the Last Glacial Maximum, the last deglaciation begun, which lasted until the early Holocene. Around much of Earth, deglaciation during the last 100 years has been accelerating as a result of climate change, partly brought on by anthropogenic changes to greenhouse gases.

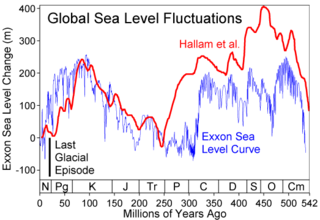

Global or eustatic sea level has fluctuated significantly over Earth's history. The main factors affecting sea level are the amount and volume of available water and the shape and volume of the ocean basins. The primary influences on water volume are the temperature of the seawater, which affects density, and the amounts of water retained in other reservoirs like rivers, aquifers, lakes, glaciers, polar ice caps and sea ice. Over geological timescales, changes in the shape of the oceanic basins and in land/sea distribution affect sea level. In addition to eustatic changes, local changes in sea level are caused by tectonic uplift and subsidence.

The early Holocene sea level rise (EHSLR) was a significant jump in sea level by about 60 m (197 ft) during the early Holocene, between about 12,000 and 7,000 years ago, spanning the Eurasian Mesolithic. The rapid rise in sea level and associated climate change, notably the 8.2 ka cooling event , and the loss of coastal land favoured by early farmers, may have contributed to the spread of the Neolithic Revolution to Europe in its Neolithic period.

The African humid period is a climate period in Africa during the late Pleistocene and Holocene geologic epochs, when northern Africa was wetter than today. The covering of much of the Sahara desert by grasses, trees and lakes was caused by changes in Earth's orbit around the Sun; changes in vegetation and dust in the Sahara which strengthened the African monsoon; and increased greenhouse gases.

References

- ↑ Fairbridge, Rhodes W. (1961). "Eustatic Changes in Sea Level". Physics and Chemistry of the Earth. 4: 99–185. Bibcode:1961PCE.....4...99F. doi:10.1016/0079-1946(61)90004-0.

- ↑ Lewis, S. E.; Sloss, C. R.; Murray-Wallace, C. V.; Woodroffe, C. D.; Smithers, S. G. (2013). "Post-glacial sea-level changes around the Australian margin: a review". Quaternary Science Reviews. 74: 115–138. Bibcode:2013QSRv...74..115L. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2012.09.006.

- ↑ Wyrwoll, Karl-Heinz; Zhu, Zhongrong; Kendrick, George; Collins, Lindsay; Eisenhauer, Anton (1995). "Holocene Sea-Level Events in Western Australia: Revisiting Old Questions". Journal of Coastal Research (Special Issue 17): 321–326. JSTOR 25735659.

- ↑ Mitrovica, J. X.; Peltier, W. R. (1991). "On postglacial geoid subsidence over the equatorial oceans". Journal of Geophysical Research. 96 (B12): 20, 053. Bibcode:1991JGR....9620053M. doi:10.1029/91jb01284.

- ↑ Fleming, Kevin; Johnston, Paul; Zwartz, Dan; Yokoyama, Yusuke; Lambeck, Kurt; Chappell, John (1998). "Refining the eustatic sea-level curve since the Last Glacial Maximum using far- and intermediate-field sites". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 163 (1–4): 327–342. Bibcode:1998E&PSL.163..327F. doi:10.1016/s0012-821x(98)00198-8.