Related Research Articles

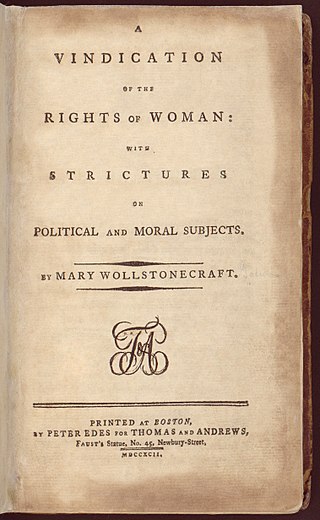

A Vindication of the Rights of Woman: with Strictures on Political and Moral Subjects (1792), written by British philosopher and women's rights advocate Mary Wollstonecraft (1759–1797), is one of the earliest works of feminist philosophy. In it, Wollstonecraft responds to those educational and political theorists of the eighteenth century who did not believe women should receive a rational education. She argues that women ought to have an education commensurate with their position in society, claiming that women are essential to the nation because they educate its children and because they could be "companions" to their husbands, rather than mere wives. Instead of viewing women as ornaments to society or property to be traded in marriage, Wollstonecraft maintains that they are human beings deserving of the same fundamental rights as men.

Egalitarianism, or equalitarianism, is a school of thought within political philosophy that builds on the concept of social equality, prioritizing it for all people. Egalitarian doctrines are generally characterized by the idea that all humans are equal in fundamental worth or moral status. As such, all citizens of a state should be accorded equal rights and treatment under the law. Egalitarian doctrines have supported many modern social movements, including the Enlightenment, feminism, civil rights, and international human rights.

Feminism is a range of socio-political movements and ideologies that aim to define and establish the political, economic, personal, and social equality of the sexes. Feminism holds the position that societies prioritize the male point of view and that women are treated unjustly in these societies. Efforts to change this include fighting against gender stereotypes and improving educational, professional, and interpersonal opportunities and outcomes for women.

Radical feminism is a perspective within feminism that calls for a radical re-ordering of society in which male supremacy is eliminated in all social and economic contexts, while recognizing that women's experiences are also affected by other social divisions such as in race, class, and sexual orientation. The ideology and movement emerged in the 1960s.

Mixed-sex education, also known as mixed-gender education, co-education, or coeducation, is a system of education where males and females are educated together. Whereas single-sex education was more common up to the 19th century, mixed-sex education has since become standard in many cultures, particularly in Western countries. Single-sex education remains prevalent in many Muslim countries. The relative merits of both systems have been the subject of debate.

Liberal feminism, also called mainstream feminism, is a main branch of feminism defined by its focus on achieving gender equality through political and legal reform within the framework of liberal democracy and informed by a human rights perspective. It is often considered culturally progressive and economically center-right to center-left. As the oldest of the "Big Three" schools of feminist thought, liberal feminism has its roots in 19th century first-wave feminism seeking recognition of women as equal citizens, focusing particularly on women's suffrage and access to education, the effort associated with 19th century liberalism and progressivism. Liberal feminism "works within the structure of mainstream society to integrate women into that structure." Liberal feminism places great emphasis on the public world, especially laws, political institutions, education and working life, and considers the denial of equal legal and political rights as the main obstacle to equality. As such liberal feminists have worked to bring women into the political mainstream. Liberal feminism is inclusive and socially progressive, while broadly supporting existing institutions of power in liberal democratic societies, and is associated with centrism and reformism. Liberal feminism tends to be adopted by white middle-class women who do not disagree with the current social structure; Zhang and Rios found that liberal feminism with its focus on equality is viewed as the dominant and "default" form of feminism. Liberal feminism actively supports men's involvement in feminism and both women and men have always been active participants in the movement; progressive men had an important role alongside women in the struggle for equal political rights since the movement was launched in the 19th century.

Equality feminism is a subset of the overall feminism movement and more specifically of the liberal feminist tradition that focuses on the basic similarities between men and women, and whose ultimate goal is the equality of all genders in all domains. This includes economic and political equality, equal access within the workplace, freedom from oppressive gender stereotyping, and an androgynous worldview.

Catharine Alice MacKinnon is an American radical feminist legal scholar, activist, and author. She is the Elizabeth A. Long Professor of Law at the University of Michigan Law School, where she has been tenured since 1990, and the James Barr Ames Visiting Professor of Law at Harvard Law School. From 2008 to 2012, she was the special gender adviser to the Prosecutor of the International Criminal Court.

Mary Daly was an American radical feminist philosopher and theologian. Daly, who described herself as a "radical lesbian feminist", taught at the Jesuit-run Boston College for 33 years. Once a practicing Roman Catholic, she had disavowed Christianity by the early 1970s. Daly retired from Boston College in 1999, after violating university policy by refusing to allow male students in her advanced women's studies classes. She allowed male students in her introductory class and privately tutored those who wanted to take advanced classes.

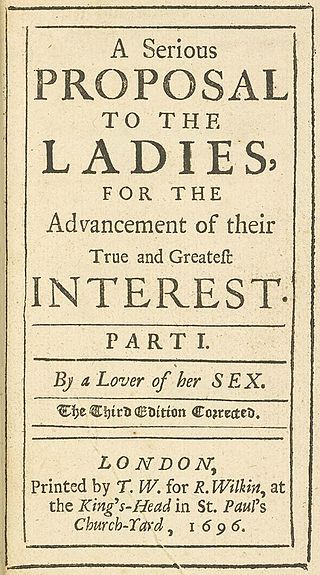

Mary Astell was an English protofeminist writer, philosopher, and rhetorician. Her advocacy of equal educational opportunities for women has earned her the title "the first English feminist." Astell is primarily remembered as one of England's inaugural advocates for women's rights. Her works, particularly "A Serious Proposal to the Ladies" and "Some Reflections Upon Marriage," argue for the fundamental intellectual equality between men and women. Her philosophical writings are thought to have influenced subsequent generations of educated women, including the literary group known as the Bluestockings. Astell, who never married, formed the majority of her close personal relationships with women. During the early 1700s, she withdrew from public life and dedicated herself to planning and managing a charitable school for girls. Astell considered herself a self-reliant, modern female; one who was on a definite mission to rescue her sex from the oppression of males.

Susan Moller Okin was a liberal feminist political philosopher and author.

Judith Sargent Stevens Murray was an early American advocate for women's rights, an essay writer, playwright, poet, and letter writer. She was one of the first American proponents of the idea of the equality of the sexes so that women, like men, had the capability of intellectual accomplishment and should be able to achieve economic independence.

Judith Plaskow is an American theologian, author, and activist known for being the first Jewish feminist theologian. After earning her doctorate at Yale University, she taught at Manhattan College for thirty-two years before becoming a professor emerita. She was one of the creators of the Journal for Feminist Studies in Religion and was its editor for the first ten years. She also helped to create B'not Esh, a Jewish feminist group that heavily inspired her writing, and a feminist section of the American Academy of Religion, an organization of which she was president in 1998.

Protofeminism is a concept that anticipates modern feminism in eras when the feminist concept as such was still unknown. This refers particularly to times before the 20th century, although the precise usage is disputed, as 18th-century feminism and 19th-century feminism are often subsumed into "feminism". The usefulness of the term protofeminist has been questioned by some modern scholars, as has the term postfeminist.

Since the 19th century, men have taken part in significant cultural and political responses to feminism within each "wave" of the movement. This includes seeking to establish equal opportunities for women in a range of social relations, generally done through a "strategic leveraging" of male privilege. Feminist men have also argued alongside writers like bell hooks, however, that men's liberation from the socio-cultural constraints of sexism and gender roles is a necessary part of feminist activism and scholarship.

Feminism is aimed at defining, establishing, and defending a state of equal political, economic, cultural, and social rights for women. It has had a massive influence on American politics. Feminism in the United States is often divided chronologically into first-wave, second-wave, third-wave, and fourth-wave feminism.

The feminist movement has effected change in Western society, including women's suffrage; greater access to education; more equitable pay with men; the right to initiate divorce proceedings; the right of women to make individual decisions regarding pregnancy ; and the right to own property.

Feminism is one theory of the political, economic, and social equality of the sexes, even though many feminist movements and ideologies differ on exactly which claims and strategies are vital and justifiable to achieve equality.

The feminist movement, also known as the women's movement, refers to a series of social movements and political campaigns for radical and liberal reforms on women's issues created by the inequality between men and women. Such issues are women's liberation, reproductive rights, domestic violence, maternity leave, equal pay, women's suffrage, sexual harassment, and sexual violence. The movement's priorities have expanded since its beginning in the 1800s, and vary among nations and communities. Priorities range from opposition to female genital mutilation in one country, to opposition to the glass ceiling in another.

References

- ↑ Gardner, Jared (2012). The Rise and Fall of Early American Magazine Culture. University of Illinois Press. p. 115. ISBN 9780252036705 . Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ↑ Baker, Jennifer J. (2005). Securing the Commonwealth. JHU Press. pp. 146–147. ISBN 9780801879722 . Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ↑ Galewski, Elizabeth (2007). "The Strange Case for Women's Capacity to Reason: Judith Sargent Murray's Use of Irony in 'On the Equality of the Sexes'". Quarterly Journal of Speech. 93 (1): 84–108. doi:10.1080/00335630701326852. S2CID 143833177.

- ↑ Villanueva Gardner, Catherine (2009). The A to Z of Feminist Philosophy. Scarecrow Press. p. 154. ISBN 9780810868397 . Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ↑ Sargent Murray, Judith (1789). On the equality of the sexes. Boston: Isaiah Thomas and Co. OCLC 310335412 – via WorldCat.

- ↑ Hughes, Mary (2011). "An Enlightened Woman: Judith Sargent Murray and the Call to Equality". Undergraduate Review. 7 (21). Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ↑ Hyser, Raymond; Arndt, j (2011). Voices of the American Past, Volume 1. Cengage Learning. p. 114. ISBN 9781111341244 . Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ↑ Eisenmann, Linda (1998). Historical Dictionary of Women's Education in the United States. Greenwood. pp. 5, 282. ISBN 9780313293238.

- ↑ Vietto, Angela (2006). Women and Authorship in Revolutionary America. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 56, 58. ISBN 9780754653387 . Retrieved 25 November 2014.

- ↑ Sargent Murray (April 1790). "On the Equality of the Sexes". The Massachusetts Magazine. 2: 132. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 Sargent Murray (April 1790). "On the Equality of the Sexes". The Massachusetts Magazine. 2: 133. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- 1 2 Sargent Murray (April 1790). "On the Equality of the Sexes". The Massachusetts Magazine. 2: 134. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ↑ Sargent Murray (April 1790). "On the Equality of the Sexes". The Massachusetts Magazine. 2: 135. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ↑ Sargent Murray (April 1790). "On the Equality of the Sexes". The Massachusetts Magazine. 2 (4): 223. Retrieved 27 November 2014.

- ↑ Sargent Murray (April 1790). "On the Equality of the Sexes". The Massachusetts Magazine. 2 (4): 224. Retrieved 27 November 2014.