Internalism and externalism are two opposite ways of integration of explaining various subjects in several areas of philosophy. These include human motivation, knowledge, justification, meaning, and truth. The distinction arises in many areas of debate with similar but distinct meanings. Internal–external distinction is a distinction used in philosophy to divide an ontology into two parts: an internal part concerning observation related to philosophy, and an external part concerning question related to philosophy.

Idealism in philosophy, also known as philosophical idealism or metaphysical idealism, is the set of metaphysical perspectives asserting that, most fundamentally, reality is equivalent to mind, spirit, or consciousness; that reality is entirely a mental construct; or that ideas are the highest type of reality or have the greatest claim to being considered "real". Because there are different types of idealism, it is difficult to define the term uniformly.

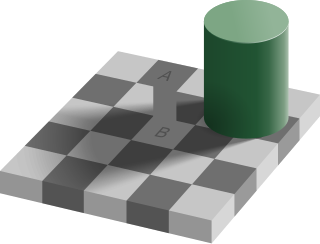

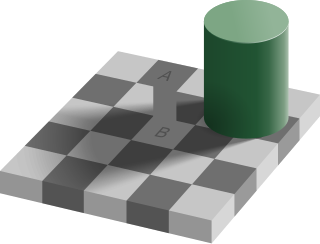

The philosophy of perception is concerned with the nature of perceptual experience and the status of perceptual data, in particular how they relate to beliefs about, or knowledge of, the world. Any explicit account of perception requires a commitment to one of a variety of ontological or metaphysical views. Philosophers distinguish internalist accounts, which assume that perceptions of objects, and knowledge or beliefs about them, are aspects of an individual's mind, and externalist accounts, which state that they constitute real aspects of the world external to the individual. The position of naïve realism—the 'everyday' impression of physical objects constituting what is perceived—is to some extent contradicted by the occurrence of perceptual illusions and hallucinations and the relativity of perceptual experience as well as certain insights in science. Realist conceptions include phenomenalism and direct and indirect realism. Anti-realist conceptions include idealism and skepticism. Recent philosophical work have expanded on the philosophical features of perception by going beyond the single paradigm of vision.

The problem of other minds is a philosophical problem traditionally stated as the following epistemological question: Given that I can only observe the behavior of others, how can I know that others have minds? The problem is that knowledge of other minds is always indirect. The problem of other minds does not negatively impact social interactions due to people having a "theory of mind" – the ability to spontaneously infer the mental states of others – supported by innate mirror neurons, a theory of mind mechanism, or a tacit theory. There has also been an increase in evidence that behavior results from cognition which in turn requires consciousness and the brain.

Chandrakirti or "Chandra" was a Buddhist scholar of the Madhyamaka school and a noted commentator on the works of Nagarjuna and those of his main disciple, Aryadeva. He wrote two influential works on madhyamaka, the Prasannapadā and the Madhyamakāvatāra.

Solipsism is the philosophical idea that only one's mind is sure to exist. As an epistemological position, solipsism holds that knowledge of anything outside one's own mind is unsure; the external world and other minds cannot be known and might not exist outside the mind.

Yogachara is an influential tradition of Buddhist philosophy and psychology emphasizing the study of cognition, perception, and consciousness through the interior lens of meditation, as well as philosophical reasoning (hetuvidyā). Yogachara was one of the two most influential traditions of Mahayana Buddhism in India, along with Madhyamaka.

In metaphysics, phenomenalism is the view that physical objects cannot justifiably be said to exist in themselves, but only as perceptual phenomena or sensory stimuli situated in time and in space. In particular, some forms of phenomenalism reduce all talk about physical objects in the external world to talk about bundles of sense data.

Subjective idealism, or empirical idealism or immaterialism, is a form of philosophical monism that holds that only minds and mental contents exist. It entails and is generally identified or associated with immaterialism, the doctrine that material things do not exist. Subjective idealism rejects dualism, neutral monism, and materialism; it is the contrary of eliminative materialism, the doctrine that all or some classes of mental phenomena do not exist, but are sheer illusions.

The Critique of Pure Reason is a book by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, in which the author seeks to determine the limits and scope of metaphysics. Also referred to as Kant's "First Critique", it was followed by his Critique of Practical Reason (1788) and Critique of Judgment (1790). In the preface to the first edition, Kant explains that by a "critique of pure reason" he means a critique "of the faculty of reason in general, in respect of all knowledge after which it may strive independently of all experience" and that he aims to reach a decision about "the possibility or impossibility of metaphysics". The term "critique" is understood to mean a systematic analysis in this context, rather than the colloquial sense of the term.

In the philosophy of perception and philosophy of mind, direct or naïve realism, as opposed to indirect or representational realism, are differing models that describe the nature of conscious experiences; out of the metaphysical question of whether the world we see around us is the real world itself or merely an internal perceptual copy of that world generated by our conscious experience.

Modern philosophy is philosophy developed in the modern era and associated with modernity. It is not a specific doctrine or school, although there are certain assumptions common to much of it, which helps to distinguish it from earlier philosophy.

Philosophical realism – usually not treated as a position of its own but as a stance towards other subject matters – is the view that a certain kind of thing has mind-independent existence, i.e. that it exists even in the absence of any mind perceiving it or that its existence is not just a mere appearance in the eye of the beholder. This includes a number of positions within epistemology and metaphysics which express that a given thing instead exists independently of knowledge, thought, or understanding. This can apply to items such as the physical world, the past and future, other minds, and the self, though may also apply less directly to things such as universals, mathematical truths, moral truths, and thought itself. However, realism may also include various positions which instead reject metaphysical treatments of reality entirely.

This glossary of philosophy is a list of definitions of terms and concepts relevant to philosophy and related disciplines, including logic, ethics, and theology.

In epistemology and the philosophy of mind, methodological solipsism has at least two distinct definitions:

- Methodological solipsism is the epistemological thesis that the individual self and its states are the sole possible or proper starting point for philosophical construction. A skeptical turn along these lines is Cartesian skepticism.

- Methodological solipsism is the thesis that the mental properties or mental states of an organism can be individuated exclusively on the basis of that state or property's relations with other internal states of the organism itself, without any reference to the society or the physical world in which the organism is embedded.

The Philosophy of mind is a branch of philosophy that deals with the nature of the mind and its relation to the body and the external world.

In epistemology, epistemological solipsism is the claim that one can only be sure of the existence of one's mind. The existence of other minds and the external world is not necessarily rejected but one can not be sure of its existence.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to metaphysics:

Ratnakīrti was an Indian Buddhist philosopher of the Yogācāra and epistemological (pramāṇavāda) schools who wrote on logic, philosophy of mind and epistemology. Ratnakīrti studied at the Vikramaśīla monastery in modern-day Bihar. He was a pupil of Jñānaśrīmitra, and Ratnakīrti refers to Jñānaśrīmitra in his work as his guru with phrases such as yad āhur guravaḥ.