The Cairo Conference also known as the First Cairo Conference, was one of the 14 summit meetings during World War II that occurred on November 22–26, 1943. The Conference was held at Cairo in Egypt between China, the United Kingdom and the United States. It outlined the Allied position against the Empire of Japan during World War II and made decisions about post-war Asia. The conference was attended by Chairman Chiang Kai-shek, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill and US President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

The military history of the United Kingdom in World War II covers the Second World War against the Axis powers, starting on 3 September 1939 with the declaration of war by the United Kingdom and France, followed by the UK's Dominions, Crown colonies and protectorates on Nazi Germany in response to the invasion of Poland by Germany. There was little, however, the Anglo-French alliance could do or did do to help Poland. The Phoney War culminated in April 1940 with the German invasion of Denmark and Norway. Winston Churchill became prime minister and head of a coalition government in May 1940. The defeat of other European countries followed – Belgium, the Netherlands, Luxembourg and France – alongside the British Expeditionary Force which led to the Dunkirk evacuation in June 1940.

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the theater of World War II that was fought in eastern Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vast Pacific Ocean theater, the South West Pacific theater, the Second Sino-Japanese War, and the Soviet–Japanese War.

The 11th Army Group was the main British Army force in Southeast Asia during the Second World War. Although a nominally British formation, it also included large numbers of troops and formations from the British Indian Army and from British African colonies, and also Nationalist Chinese and United States units.

The British Fourteenth Army was a multi-national force comprising units from Commonwealth countries during the Second World War. As well as British Army units, many of its units were from the Indian Army and there were also significant contributions from the British Army's West and East African divisions. It was often referred to as the "Forgotten Army" because its operations in the Burma campaign were overlooked by the contemporary press, and remained more obscure than those of the corresponding formations in Europe for long after the war. For most of the Army's existence, it was commanded by Lieutenant-General William Slim.

The British Pacific Fleet (BPF) was a Royal Navy formation that saw action against Japan during the Second World War. It was formed from aircraft carriers, other surface warships, submarines and supply vessels of the RN and British Commonwealth navies in November 1944.

South East Asia Command (SEAC) was the body set up to be in overall charge of Allied operations in the South-East Asian Theatre during the Second World War.

The Burma campaign was a series of battles fought in the British colony of Burma. It was part of the South-East Asian theatre of World War II and primarily involved forces of the Allies against the invading forces of the Empire of Japan. Imperial Japan was supported by the Thai Phayap Army, as well as two collaborationist independence movements and armies. Nominally independent puppet states were established in the conquered areas and some territories were annexed by Thailand. In 1942 and 1943, the international Allied force in British India launched several failed offensives to retake lost territories. Fighting intensified in 1944, and British Empire forces peaked at around 1 million land and air forces. These forces were drawn primarily from British India, with British Army forces, 100,000 East and West African colonial troops, and smaller numbers of land and air forces from several other Dominions and Colonies. These additional forces allowed the Allied recapture of Burma in 1945.

The South-East Asian Theatre of World War II consisted of the campaigns of the Pacific War in the Philippines, Thailand, Indonesia, Indochina, Burma, India, Malaya and Singapore between 1941 and 1945.

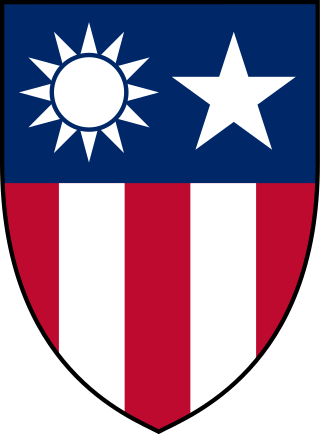

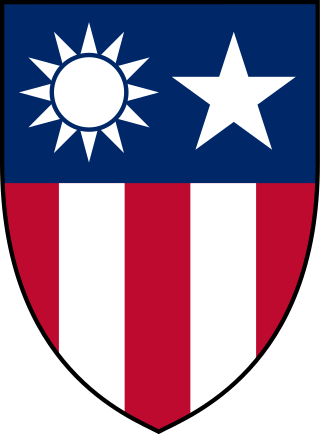

China Burma India Theater (CBI) was the United States military designation during World War II for the China and Southeast Asian or India–Burma (IBT) theaters. Operational command of Allied forces in the CBI was officially the responsibility of the Supreme Commanders for South East Asia or China. In practice, U.S. forces were usually overseen by General Joseph Stilwell, the Deputy Allied Commander in China; the term "CBI" was significant in logistical, material and personnel matters; it was and is commonly used within the US for these theaters.

South West Pacific Area (SWPA) was the name given to the Allied supreme military command in the South West Pacific Theatre of World War II. It was one of four major Allied commands in the Pacific War. SWPA included the Philippines, Borneo, the Dutch East Indies, East Timor, Australia, the Territories of Papua and New Guinea, and the western part of the Solomon Islands. It primarily consisted of United States and Australian forces, although Dutch, Filipino, British and other Allied forces also served in the SWPA.

Operation Dracula was a World War II-airborne and amphibious attack on Rangoon by British and Anglo-Indian forces during the Burma Campaign.

Admiral Sir Manley Laurence Power KCB, CBE, DSO & Bar, DL was a Royal Navy admiral who fought in World War II as a captain and later rose to more senior ranks, including the NATO position Allied Commander-in-Chief, Channel. One of his chief accomplishments was leading the 26th Destroyer Flotilla into the Malacca Strait during Operation Dukedom to sink the Japanese cruiser Haguro.

Operation Tiderace was the codename of the British plan to retake Singapore following the Japanese surrender in 1945. The liberation force was led by Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander of South East Asia Command. Tiderace was initiated in coordination with Operation Zipper, which involved the liberation of Malaya.

The Burma campaign in the South-East Asian Theatre of World War II was fought primarily by British Commonwealth, Chinese and United States forces against the forces of Imperial Japan, who were assisted by the Burmese National Army, the Indian National Army, and to some degree by Thailand. The British Commonwealth land forces were drawn primarily from the United Kingdom, British India and Africa.

The Battle of Elephant Point was an airborne operation at the mouth of the Rangoon River conducted by a composite Gurkha airborne battalion that took place on 1 May 1945. In March 1945, plans were made for an assault on Rangoon, the capital of Burma, as a stepping-stone on the way to recapturing Malaya and Singapore. Initial plans for the assault on the city had called for a purely land-based approach by British Fourteenth Army, but concerns about heavy Japanese resistance led to this being modified with the addition of a joint amphibious-airborne assault. This assault, led by 26th Indian Division, would sail up the Rangoon River, but before it could do so, the river would have to be cleared of Japanese and British mines. In order to achieve this, coastal defences along the river would have to be neutralized, including a battery at Elephant Point.

The Bombing of Singapore (1944–1945) was a military campaign conducted by the Allied air forces during World War II. United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) long-range bomber units conducted 11 air raids on Japanese-occupied Singapore between November 1944 and March 1945. Most of these raids targeted the island's naval base and dockyard facilities, and minelaying missions were conducted in nearby waters. After the American bombers were redeployed, the British Royal Air Force assumed responsibility for minelaying operations near Singapore and these continued until 24 May 1945.

The Eastern Fleet, later called the East Indies Fleet, was a fleet of the Royal Navy which existed between 1941 and 1952.

Operation Jurist referred to the British recapture of Penang following Japan's surrender in 1945. Jurist was launched as part of Operation Zipper, the overall British plan to liberate Malaya, including Singapore.