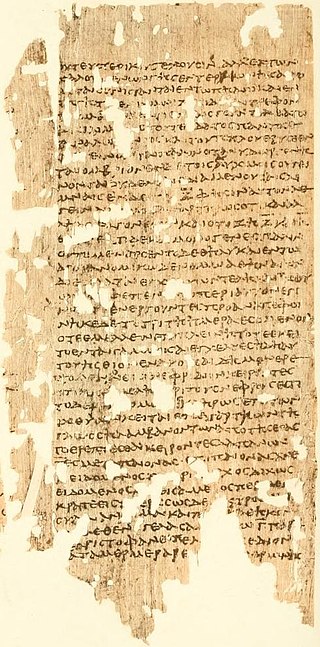

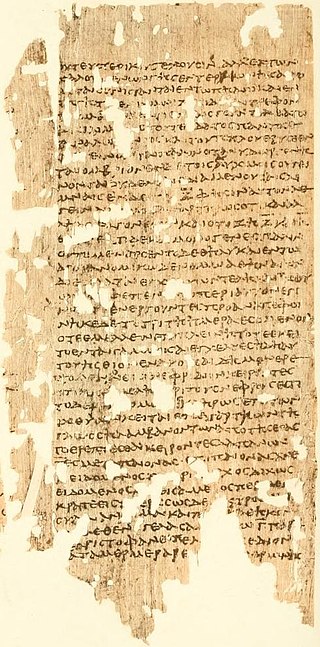

Beowulf is an Old English epic poem in the tradition of Germanic heroic legend consisting of 3,182 alliterative lines. It is one of the most important and most often translated works of Old English literature. The date of composition is a matter of contention among scholars; the only certain dating is for the manuscript, which was produced between 975 and 1025 AD. Scholars call the anonymous author the "Beowulf poet". The story is set in pagan Scandinavia in the 5th and 6th centuries. Beowulf, a hero of the Geats, comes to the aid of Hrothgar, the king of the Danes, whose mead hall Heorot has been under attack by the monster Grendel for twelve years. After Beowulf slays him, Grendel's mother takes revenge and is in turn defeated. Victorious, Beowulf goes home to Geatland and becomes king of the Geats. Fifty years later, Beowulf defeats a dragon, but is mortally wounded in the battle. After his death, his attendants cremate his body and erect a barrow on a headland in his memory.

Old English literature refers to poetry and prose written in Old English in early medieval England, from the 7th century to the decades after the Norman Conquest of 1066, a period often termed Anglo-Saxon England. The 7th-century work Cædmon's Hymn is often considered as the oldest surviving poem in English, as it appears in an 8th-century copy of Bede's text, the Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Poetry written in the mid 12th century represents some of the latest post-Norman examples of Old English. Adherence to the grammatical rules of Old English is largely inconsistent in 12th-century work, and by the 13th century the grammar and syntax of Old English had almost completely deteriorated, giving way to the much larger Middle English corpus of literature.

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication in which knowledge, art, ideas and culture are received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another. The transmission is through speech or song and may include folktales, ballads, chants, prose or poetry. The information is mentally recorded by oral repositories, sometimes termed "walking libraries", who are usually also performers. Oral tradition is a medium of communication for a society to transmit oral history, oral literature, oral law and other knowledge across generations without a writing system, or in parallel to a writing system. It is the most widespread medium of human communication. They often remain in use in the modern era throughout for cultural preservation.

Milman Parry was an American Classicist whose theories on the origin of Homer's works have revolutionized Homeric studies to such a fundamental degree that he has been described as the "Darwin of Homeric studies". In addition, he was a pioneer in the discipline of oral tradition.

Albert Bates Lord was a professor of Slavic and comparative literature at Harvard University who carried on Milman Parry's research on epic poetry after Parry's death.

Paul Jules Antoine Meillet was one of the most important French linguists of the early 20th century. He began his studies at the Sorbonne University, where he was influenced by Michel Bréal, the Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure, and the members of the L'Année sociologique. In 1890 he was part of a research trip to the Caucasus, where he studied the Armenian language. After his return, de Saussure had gone back to Geneva, so Meillet continued the series of lectures on comparative linguistics that de Saussure had given.

A characteristic of Homer's style is the use of epithets, as in "rosy-fingered" Dawn or "swift-footed" Achilles. Epithets are used because of the constraints of the dactylic hexameter and because of the oral transmission of the poems; they are mnemonic aids to the singer and the audience alike.

The Homeric Question concerns the doubts and consequent debate over the identity of Homer, the authorship of the Iliad and Odyssey, and their historicity. The subject has its roots in classical antiquity and the scholarship of the Hellenistic period, but has flourished among Homeric scholars of the 19th, 20th, and 21st centuries.

Homeric scholarship is the study of any Homeric topic, especially the two large surviving epics, the Iliad and Odyssey. It is currently part of the academic discipline of classical studies. The subject is one of the oldest in education.

Oral poetry is a form of poetry that is composed and transmitted without the aid of writing. The complex relationships between written and spoken literature in some societies can make this definition hard to maintain.

Francis Peabody Magoun, Jr. MC was one of the seminal figures in the study of medieval and English literature in the 20th century, a scholar of subjects as varied as soccer and ancient Germanic naming practices, and translator of numerous important texts. Though an American, he served in the British Royal Flying Corps as a lieutenant during World War I. Magoun was victor in five aerial combats and was also decorated with Britain's Military Cross for gallantry.

The Greek word aoidos referred to a classical Greek singer. In modern Homeric scholarship aoidos is used by some as the technical term for a skilled oral epic poet in the tradition to which the Iliad and Odyssey are believed to belong.

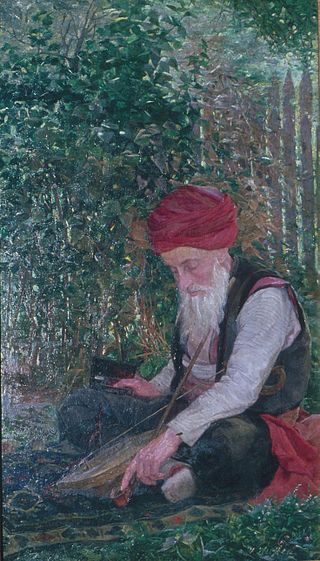

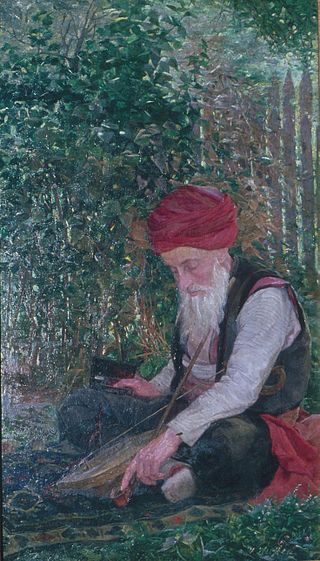

Avdo Međedović was a Slavic Muslim guslar from Montenegro. He was the most versatile and skillful performer of all those encountered by Milman Parry and Albert Lord during their research on the oral epic tradition of Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro in the 1930s. At Parry's request, Avdo sang songs he already knew and some songs he heard in front of Parry, convincing him that someone Homer-like could produce a poem so long. Avdo dictated, over five days, a version of the well-known theme The Wedding of Meho Smailagić that was 12,323 lines long, saying on the fifth day to Nikola that he knew even longer songs. On another occasion, he sang over several days an epic of 13,331 lines. He said he had several others of similar length in his repertoire. In Parry's first tour, over 80,000 lines were transcribed.

Oral-formulaic theory in Anglo-Saxon poetry refers to the application of the hypotheses of Milman Parry and Albert Lord on the Homeric Question to verse written in Old English. That is, the theory proposes that certain features of at least some of the poetry may be explained by positing oral-formulaic composition. While Anglo-Saxon epic poetry may bear some resemblance to Ancient Greek epics such as the Iliad and Odyssey, the question of if and how Anglo-Saxon poetry was passed down through an oral tradition remains a subject of debate, and the question for any particular poem unlikely to be answered with perfect certainty.

The Singer of Tales is a book by Albert Lord that formulates oral tradition as a theory of literary composition and its applications to Homeric and medieval epic. Lord builds on the research of Milman Parry and their joint work recording Balkan guslar poets. It was published in 1960.

John Miles Foley was a scholar of comparative oral tradition, particularly medieval and Old English literature, Homer and Serbian epic. He was the founder of the academic journal Oral Tradition and the Center for Studies in Oral Tradition at the University of Missouri, where he was Curators' Professor of Classical Studies and English and W. H. Byler Endowed Chair in the Humanities.

The Kângë Kreshnikësh are the traditional songs of the heroic legendary cycle of Albanian epic poetry. They are the product of Albanian culture and folklore orally transmitted down the generations by the Albanian lahutarë who perform them singing to the accompaniment of the lahutë. The Albanian traditional singing of epic verse from memory is one of the last survivors of its kind in modern Europe, and the last survivor of the Balkan traditions. The poems of the cycle belong to the heroic genre, reflecting the legends that portray and glorify the heroic deeds of the warriors of indefinable old times. The epic poetry about past warriors is an Indo-European tradition shared with South Slavs, but also with other heroic cultures such as those of early Greece, classical India, early medieval England and medieval Germany.

Albanian epic poetry is a form of epic poetry created by the Albanian people. It consists of a longstanding oral tradition still very much alive. A good number of Albanian epic singers can be found today in Kosovo and northern Albania, and some also in Montenegro. The Albanian traditional singing of epic verse from memory is one of the last survivors of its kind in modern Europe, and the last survivor of the Balkan traditions.

Dr. Zlatan Čolaković was a Croatian Homerist, philologist and researcher.

Bosniak epic poetry is a form of epic poetry originating in today's Bosnia and Herzegovina and in the Sandžak region, which is a part of modern-day Serbia and Montenegro. Bosniak epic poetry developed during the Ottoman period. Historically, they were accompanied by the Gusle. The theory of oral-formulaic composition was developed also through the scholarly study of Bosnian epic verse.