Related Research Articles

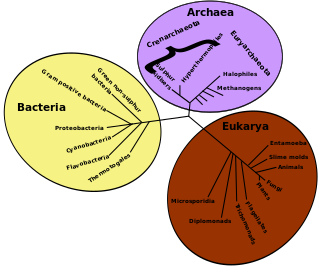

Ecology is the natural science of the relationships among living organisms and their environment. Ecology considers organisms at the individual, population, community, ecosystem, and biosphere levels. Ecology overlaps with the closely related sciences of biogeography, evolutionary biology, genetics, ethology, and natural history.

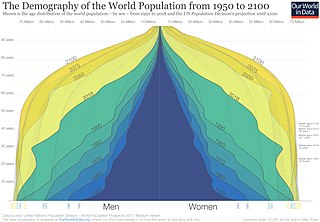

Demography is the statistical study of human populations: their size, composition, and how they change through the interplay of fertility (births), mortality (deaths), and migration.

In ecology, a niche is the match of a species to a specific environmental condition. It describes how an organism or population responds to the distribution of resources and competitors and how it in turn alters those same factors. "The type and number of variables comprising the dimensions of an environmental niche vary from one species to another [and] the relative importance of particular environmental variables for a species may vary according to the geographic and biotic contexts".

Human ecology is an interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary study of the relationship between humans and their natural, social, and built environments. The philosophy and study of human ecology has a diffuse history with advancements in ecology, geography, sociology, psychology, anthropology, zoology, epidemiology, public health, and home economics, among others.

This glossary of ecology is a list of definitions of terms and concepts in ecology and related fields. For more specific definitions from other glossaries related to ecology, see Glossary of biology, Glossary of evolutionary biology, and Glossary of environmental science.

Ecological modernization is a school of thought that argues that both the state and the market can work together to protect the environment. It has gained increasing attention among scholars and policymakers in the last several decades internationally. It is an analytical approach as well as a policy strategy and environmental discourse.

The Chicago school refers to a school of thought in sociology and criminology originating at the University of Chicago whose work was influential in the early 20th century.

Environmental sociology is the study of interactions between societies and their natural environment. The field emphasizes the social factors that influence environmental resource management and cause environmental issues, the processes by which these environmental problems are socially constructed and define as social issues, and societal responses to these problems.

Legitimation, legitimization (US), or legitimisation (UK) is the act of providing legitimacy. Legitimation in the social sciences refers to the process whereby an act, process, or ideology becomes legitimate by its attachment to norms and values within a given society. It is the process of making something acceptable and normative to a group or audience.

Evolutionary ecology lies at the intersection of ecology and evolutionary biology. It approaches the study of ecology in a way that explicitly considers the evolutionary histories of species and the interactions between them. Conversely, it can be seen as an approach to the study of evolution that incorporates an understanding of the interactions between the species under consideration. The main subfields of evolutionary ecology are life history evolution, sociobiology, the evolution of interspecific interactions and the evolution of biodiversity and of ecological communities.

Ecological anthropology is a sub-field of anthropology and is defined as the "study of cultural adaptations to environments". The sub-field is also defined as, "the study of relationships between a population of humans and their biophysical environment". The focus of its research concerns "how cultural beliefs and practices helped human populations adapt to their environments, and how people used elements of their culture to maintain their ecosystems". Ecological anthropology developed from the approach of cultural ecology, and it provided a conceptual framework more suitable for scientific inquiry than the cultural ecology approach. Research pursued under this approach aims to study a wide range of human responses to environmental problems.

In ecology, r/K selection theory relates to the selection of combinations of traits in an organism that trade off between quantity and quality of offspring. The focus on either an increased quantity of offspring at the expense of reduced individual parental investment of r-strategists, or on a reduced quantity of offspring with a corresponding increased parental investment of K-strategists, varies widely, seemingly to promote success in particular environments. The concepts of quantity or quality offspring are sometimes referred to as "cheap" or "expensive", a comment on the expendable nature of the offspring and parental commitment made. The stability of the environment can predict if many expendable offspring are made or if fewer offspring of higher quality would lead to higher reproductive success. An unstable environment would encourage the parent to make many offspring, because the likelihood of all of them surviving to adulthood is slim. In contrast, more stable environments allow parents to confidently invest in one offspring because they are more likely to survive to adulthood.

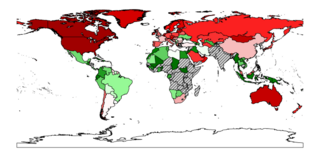

Ecological debt refers to the accumulated debt seen by some campaigners as owed by the Global North to Global South countries, due to the net sum of historical environmental injustice, especially through resource exploitation, habitat degradation, and pollution by waste discharge. The concept was coined by Global Southerner non-governmental organizations in the 1990s and its definition has varied over the years, in several attempts of greater specification.

In ecology, a community is a group or association of populations of two or more different species occupying the same geographical area at the same time, also known as a biocoenosis, biotic community, biological community, ecological community, or life assemblage. The term community has a variety of uses. In its simplest form it refers to groups of organisms in a specific place or time, for example, "the fish community of Lake Ontario before industrialization".

Patch dynamics is an ecological perspective that the structure, function, and dynamics of ecological systems can be understood through studying their interactive patches. Patch dynamics, as a term, may also refer to the spatiotemporal changes within and among patches that make up a landscape. Patch dynamics is ubiquitous in terrestrial and aquatic systems across organizational levels and spatial scales. From a patch dynamics perspective, populations, communities, ecosystems, and landscapes may all be studied effectively as mosaics of patches that differ in size, shape, composition, history, and boundary characteristics.

Limiting similarity is a concept in theoretical ecology and community ecology that proposes the existence of a maximum level of niche overlap between two given species that will allow continued coexistence.

William P. Barnett is an American organizational theorist, and is the Thomas M. Siebel Professor of Business Leadership, Strategy, and Organizations at the Stanford Graduate School of Business. He is the BP Faculty Fellow in Global Management; Senior Fellow, Woods Institute for the Environment at Stanford; Director of the Center for Global Business and the Economy; Director of the Business Strategies for Environmental Sustainability Executive Program; and Codirector of the Executive Program in Strategy and Organization.

In organizational theory and organizational behavior, imprinting is a core concept describing how the past affects the present. Imprinting is generally defined as a process whereby, during a brief period of susceptibility, a focal entity or actor develops characteristics that reflect prominent features of the environment, and these characteristics continue to persist despite significant environmental changes in subsequent periods. This definition emphasizes three key elements of imprinting:

- brief sensitive periods of transition during which the focal entity exhibits high susceptibility to external influences;

- a process whereby the focal entity comes to reflect elements of its environment during a sensitive period; and

- the persistence of imprints despite subsequent environmental changes.

Michael Thomas Hannan is an American sociologist who serves as the StrataCom Professor of Management at Stanford University, where he is also a professor of management at the Stanford Graduate School of Business.

Organizational adaptation is a concept in organization theory and strategic management that is used to describe the relationship between an organization and its environment. The conceptual roots of organizational adaptation borrows ideas from organizational ecology, evolutionary economics, industrial and organizational psychology, and sociology. A systematic review of 50 years worth of literature defined organizational adaptation as "intentional decision-making undertaken by organizational members, leading to observable actions that aim to reduce the distance between an organization and its economic and institutional environments".

References

- 1 2 Douma, Sytse and Hein Schreuder, 2013. "Economic Approaches to Organizations". 5th edition. London: Pearson ISBN 0273735292 • ISBN 9780273735298

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hannan, M., & Freeman, J. (1977). The population ecology of organizations. American Journal of Sociology 82(5), 929–964.

- 1 2 3 4 Baum, J., & Shipilov, A. (2006). Ecological approaches to organizations. In S. Clegg, C. Hardy, T. Lawrence, & W. Nord (Eds.) The Sage handbook of organization studies (pp. 55–110.) London: Sage Publications.

- ↑ Evan, W. (1966). "The organization-set" in J. Thompson (ed.) Approaches to Organizational Design. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- ↑ Trist, E. (1977). A Concept of Organizational Ecology. Australian Journal of Management 2(2), 161–175.

- ↑ Singh, J., & Lumsden, C. (1990). Theory and research in organizational ecology. Annual Review of Sociology 16(1), 161–195.

- ↑ Carroll, G. (1984). Organizational ecology. Annual Review of Sociology 10(1), 71–93.