Related Research Articles

The Ottoman Empire, historically and colloquially known as the Turkish Empire, was an empire that controlled much of Southeast Europe, West Asia, and North Africa between the 14th and early 20th centuries. The empire also controlled parts of southeastern Central Europe from the early 16th to the early 18th century.

Sharia is a body of religious law that forms a part of the Islamic tradition based on scriptures of Islam, particularly the Quran and the Hadith. In Arabic, the term sharīʿah refers to God's immutable divine law and this referencing is contrasted with fiqh, which refers to its interpretations by Islamic scholars. Fiqh, practical application side of sharia in a sense, was elaborated over the centuries by legal opinions issued by qualified jurists and sharia has never been the sole valid legal system in Islam historically; has always been used alongside customary law from the beginning, and applied in courts by ruler-appointed judges, integrated with various economic, criminal and administrative laws issued by Muslim rulers

In Islam, the ulama, also spelled ulema, are scholars of Islamic doctrine and law. They are considered the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious knowledge in Islam.

The Tanzimat was a period of reform in the Ottoman Empire that began with the Gülhane Hatt-ı Şerif in 1839 and ended with the First Constitutional Era in 1876. The Tanzimat era began with the purpose not of radical transformation, but of modernization, desiring to consolidate the social and political foundations of the Ottoman Empire. It was characterised by various attempts to modernise the Ottoman Empire and to secure its territorial integrity against internal nationalist movements and external aggressive powers. The reforms encouraged Ottomanism among the diverse ethnic groups of the Empire and attempted to stem the tide of the rise of nationalism in the Ottoman Empire.

Mehmed Fuad Pasha, sometimes known as Keçecizade Mehmed Fuad Pasha and commonly known as Fuad Pasha, was an Ottoman administrator and statesman, who is known for his prominent role in the Tanzimat reforms of the mid-19th-century Ottoman Empire, as well as his leadership during the 1860 Mount Lebanon civil war in Syria. He represented a modern Ottoman era, given his openness to European-style modernization as well as the reforms he helped to enact.

This article gives an overview of liberalism in Turkey. Liberalism was introduced in the Ottoman Empire during the Tanzimat period of reformation.

In the Ottoman Empire, a millet was an independent court of law pertaining to "personal law" under which a confessional community was allowed to rule itself under its own laws.

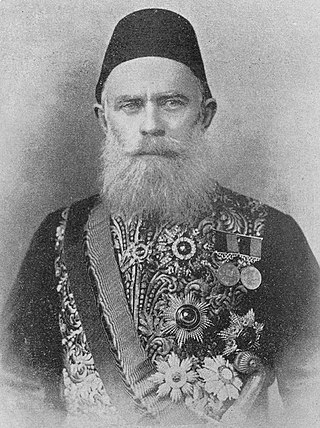

Ahmed Cevdet Pasha or Jevdet Pasha in English was an Ottoman scholar, intellectual, bureaucrat, administrator, and historian who was a prominent figure in the Tanzimat reforms of the Ottoman Empire. He was the head of the Mecelle commission that codified Islamic law for the first time in response to the Westernization of law. He is often regarded as a pioneer in the codification of a civil law based on the European legal system. The Mecelle remained intact in several modern Arab states in the early and mid-20th-century. In addition to Turkish, he was proficient in Arabic, Persian, French and Bulgarian. He wrote numerous books on history, law, grammar, linguistics, logic and astronomy.

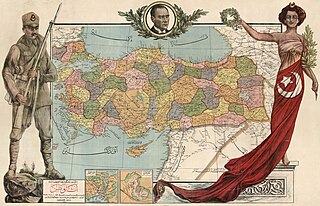

Atatürk's Reforms were a series of political, legal, religious, cultural, social, and economic policy changes, designed to convert the new Republic of Turkey into a secular nation-state, implemented under the leadership of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in accordance with the Kemalist framework. His political party, the Republican People's Party (CHP), ran Turkey as a one-party state and implemented these reforms, starting in 1923. After Atatürk's death, his successor İsmet İnönü continued the one-party rule and Kemalist style reforms until the CHP lost to the Democrat Party in Turkey's second multi-party election in 1950.

Mehmed Emin Âli Pasha, also spelled as Mehmed Emin Aali was a prominent Ottoman statesman during the Tanzimat period, best known as the architect of the Ottoman Reform Edict of 1856, and for his role in the Treaty of Paris (1856) that ended the Crimean War. Âli Pasha was widely regarded as a deft and able statesman, and often credited with preventing an early break-up of the empire.

The Mecelle-i Ahkâm-ı Adliye, or the Mecelle in short, was the civil code of the Ottoman Empire in the late 19th and early 20th century. It is the first codification of Sharia law by an Islamic nation.

The Constitution of the Ottoman Empire was the first and only constitution of the Ottoman Empire. Written by members of the Young Ottomans, particularly Midhat Pasha, during the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II, the constitution was in effect from 1876 to 1878 in a period known as the First Constitutional Era, and from 1908 to 1922 in the Second Constitutional Era. After Abdul Hamid's political downfall in the 31 March Incident, the Constitution was amended to transfer more power from the sultan and the appointed Senate to the popularly-elected lower house: the Chamber of Deputies.

Islam and modernity is a topic of discussion in contemporary sociology of religion. The history of Islam chronicles different interpretations and approaches. Modernity is a complex and multidimensional phenomenon rather than a unified and coherent one. It has historically had different schools of thought moving in many directions.

Palestinian law is the law administered by the Palestinian National Authority within the territory pursuant to the Oslo Accords. It has an unusually unsettled status, as of 2023, due to the complex legal history of the area. Palestinian law includes many of the legal regimes and precepts used in Palestinian ruled territory and administered by the Palestinian Authority and Hamas, which is not an independent nation-state.

The language of the court and government of the Ottoman Empire was Ottoman Turkish, but many other languages were in contemporary use in parts of the empire. The Ottomans had three influential languages, known as "Alsina-i Thalātha", that were common to Ottoman readers: Ottoman Turkish, Arabic and Persian. Turkish was spoken by the majority of the people in Anatolia and by the majority of Muslims of the Balkans except in Albania, Bosnia, and various Aegean Sea islands; Persian was initially a literary and high-court language used by the educated in the Ottoman Empire before being displaced by Ottoman Turkish; and Arabic, which was the legal and religious language of the empire, was also spoken regionally, mainly in Arabia, North Africa, Mesopotamia and the Levant.

Takvim-i Vekayi was the first fully Turkish language newspaper. It was launched in 1831 by Sultan Mahmud II, taking over from the Moniteur ottoman as the Official Gazette of the Ottoman Empire. With the beginning of the Tanzimat reform period, Takvim-i Vekayi produced versions in multiple language editions. It ceased publication in 1878, resuming in 1891–2, before being closed again. It resumed in 1908 until around 1922. In the 1831-1878 period it published a total of 2119 issues - an average of slightly less than one a week.

The Ottoman Empire was governed by different sets of laws during its existence. The Qanun, sultanic law, co-existed with religious law. Legal administration in the Ottoman Empire was part of a larger scheme of balancing central and local authority. Ottoman power revolved crucially around the administration of the rights to land, which gave a space for the local authority develop the needs of the local millet. The jurisdictional complexity of the Ottoman Empire was aimed to permit the integration of culturally and religiously different groups.

The Ilmiye is one of four institutions that existed within the state organisation of the Ottoman Empire, the other three being the Imperial (mülkiye) institution; the military (seyfiye) institution; and the administrative (kalemiye) institution. The function of the Ilmiye was to propagate the Muslim religion, to ensure that Islamic law was enforced properly within the courts, as well as to ensure that it was interpreted and taught properly within the Ottoman school system. The development of the Ilmiye took place over the course of the sixteenth century, absorbing the Ulama, the educated class of Muslim legal scholars, in the process.

The Law of Jordan is influenced by Ottoman law and European laws. The Constitution of Jordan of 1952 affirmed Islam as the state religion, but it did not state that Islam is the source of legislation. Jordanian penal code has been influenced by the French Penal Code of 1810.

References

- ↑ "Ottoman Nizamiye Courts: Law and Modernity". Comparative Legal History. 1: 285–290. doi:10.5235/2049677X.1.2.285. S2CID 159732453.

- ↑ Wood, Leonard G. H. Islamic Legal Revival: Reception of European Law and Transformations in Islamic Legal Thought in Egypt, 1875-1952. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2016. Print. Page 35.

- ↑ Rubin, Avi. Ottoman Nizamiye Courts: Law and Modernity. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. Print. Page 78.

- ↑ Epstein, Lee; O'Connor, Karen; Grub, Diana. "Middle East" (PDF). Legal Traditions and Systems: an International Handbook. Greenwood Press. pp. 223–224.

- ↑ Selçuk Akşin Somel. "Review of "Ottoman Nizamiye Courts. Law and Modernity"" (PDF). Sabancı Üniversitesi. p. 2.

- ↑ Rubin, Avi. Ottoman Nizamiye Courts: Law and Modernity. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. Print. Page 63.

- ↑ Findley, Carter V. Turkey, Islam, Nationalism, and Modernity: A History, 1789-2007. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 2010. Print.

- ↑ Findley, Carter V. Turkey, Islam, Nationalism, and Modernity: A History, 1789-2007. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 2010. Print.

- ↑ "Ottoman Nizamiye Courts: Law and Modernity". Comparative Legal History. 1: 285–290. doi:10.5235/2049677X.1.2.285. S2CID 159732453.

- ↑ Findley, Carter V. Turkey, Islam, Nationalism, and Modernity: A History, 1789-2007. New Haven, CT: Yale UP, 2010. Print.

- ↑ "Ottoman Nizamiye Courts: Law and Modernity". Comparative Legal History. 1: 285–290. doi:10.5235/2049677X.1.2.285. S2CID 159732453.

- ↑ Wood, Leonard G. H. Islamic Legal Revival: Reception of European Law and Transformations in Islamic Legal Thought in Egypt, 1875-1952. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2016. Print. Page 35.

- ↑ Wood, Leonard G. H. Islamic Legal Revival: Reception of European Law and Transformations in Islamic Legal Thought in Egypt, 1875-1952. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2016. Print. Page 55.

- ↑ Cleveland, William L, The Making of an Arab Nationalist: Ottomanism and Arabism in the Life and Thought of SatiÊ» Al-Husri. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 1971, page 13.

- ↑ Rubin, Avi, Ottoman Nizamiye Courts: Law and Modernity, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, page 117-20.

- ↑ Epstein, Lee; O'Connor, Karen; Grub, Diana. "Middle East" (PDF). Legal Traditions and Systems: an International Handbook. Greenwood Press. pp. 223–224

- ↑ "Ottoman Nizamiye Courts: Law and Modernity". Comparative Legal History. 1: 285–290. doi:10.5235/2049677X.1.2.285. S2CID 159732453.

- ↑ Epstein, Lee; O'Connor, Karen; Grub, Diana. "Middle East" (PDF). Legal Traditions and Systems: an International Handbook. Greenwood Press. pp. 223–224.

- ↑ Selçuk Akşin Somel. "Review of "Ottoman Nizamiye Courts. Law and Modernity"" (PDF). Sabancı Üniversitesi. p. 2.

- ↑ Epstein, Lee; O'Connor, Karen; Grub, Diana. "Middle East" (PDF). Legal Traditions and Systems: an International Handbook. Greenwood Press. pp. 223–224.

- ↑ Lee Epstein; Karen O’Connor; Diana Grub. "Middle East" (PDF). Legal Traditions and Systems: an International Handbook. Greenwood Press. pp. 223–224.

- ↑ "Ottoman Nizamiye Courts: Law and Modernity". Comparative Legal History. 1: 285–290. doi:10.5235/2049677X.1.2.285. S2CID 159732453.