Related Research Articles

Hashim al-Atassi was a Syrian nationalist and statesman and the President of Syria from 1936 to 1939, 1949 to 1951 and 1954 to 1955.

Shukri al-Quwatli was the first president of post-independence Syria. He began his career as a dissident working towards the independence and unity of the Ottoman Empire's Arab territories and was consequently imprisoned and tortured for his activism. When the Kingdom of Syria was established, Quwatli became a government official, though he was disillusioned with monarchism and co-founded the republican Independence Party. Quwatli was immediately sentenced to death by the French who took control over Syria in 1920. Afterward, he based himself in Cairo where he served as the chief ambassador of the Syrian-Palestinian Congress, cultivating particularly strong ties with Saudi Arabia. He used these connections to help finance the Great Syrian Revolt (1925–1927). In 1930, the French authorities pardoned Quwatli and thereafter, he returned to Syria, where he gradually became a principal leader of the National Bloc. He was elected president of Syria in 1943 and oversaw the country's independence three years later.

Awni Abd al-Hadi, aka Auni Bey Abdel Hadi was a Palestinian political figure. He was educated in Beirut, Istanbul, and at the Sorbonne University in Paris. His wife was Tarab Abd al-Hadi, a Palestinian activist and feminist.

Syrian Turkmen, also referred to as Syrian Turkomans, Turkish Syrians, or simply Syrian Turks or Turks of Syria, are Syrian citizens of Turkish origin who mainly trace their roots to Anatolia. Turkish-speaking Syrian Turkmen make up the third largest ethnic group in the country, after the Arabs and Kurds respectively.

Wasfi al-Atassi (1888–1933) was a Syrian nationalist, statesman and one of the original writers of the Syrian constitution.

Al-Fatat or the Young Arab Society was an underground Arab nationalist organization in the Ottoman Empire. Its aims were to gain independence and unify various Arab territories that were then under Ottoman rule. It found adherents in areas such as Syria. The organization maintained contacts with the reform movement in the Ottoman Empire and included many radicals and revolutionaries, such as Abd al-Mirzai. They were closely linked to the Al-Ahd, or Covenant Society, who had members in positions within the military, most were quickly dismissed after Enver Pasha gained control in Turkey. This organization's parallel in activism were the Young Turks, who had a similar agenda that pertained to Turkish nationalism.

Martyrs' Day is a Syrian and Lebanese national holiday commemorating the Syrian and Lebanese nationalists executed in Damascus and Beirut on 6 May 1916 by Jamal Pasha, also known as 'Al Jazzar' or 'The Butcher', the Ottoman wāli of Greater Syria. They were executed in both the Marjeh Square in Damascus and Burj Square in Beirut. Both plazas have since been renamed Martyrs' Square.

Jamil Mardam Bey, was a Syrian politician. He was born in Damascus to a prominent aristocratic family. He is a descendant of the Ottoman general, statesman and Grand Vizier Lala Mustafa Pasha and the penultimate Mamluk ruler Qansuh al Ghuri. He studied at the school of Political Science in Paris and it was there that his political career started.

As'ad Pasha al-Azm was the governor of Damascus under Ottoman rule from 1743 to his deposition in 1757. He was responsible for the construction of several architectural works in the city and other places in Syria.

Haqqi al-Azm was a Syrian politician active during the late Ottoman period and during the First Syrian Republic. From 1932 to 1934, he served as Prime Minister of Syria under the presidency of Muhammad Ali Bey al-Abid. He was a co-founder of the Ottoman Party for Administrative Decentralization.

Al-Azm family is a prominent Damascene family. Their political influence in Ottoman Syria began in the 18th century when members of the family administered Maarrat al-Nu'man and Hama. A scion of the family, Ismail Pasha al-Azm, was appointed wāli of Damascus Eyalet in 1725. Between 1725 and 1783, members of the family, including As'ad Pasha al-Azm, held power in Damascus for 47 years, in addition to periodical appointments in Sidon Eyalet, Tripoli Eyalet, Hama, Aleppo Eyalet, and Egypt Eyalet. The family's influence declined in the 19th century, failing to establish a true dynasty.

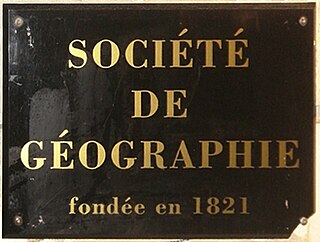

The Arab Congress of 1913 met in a hall of the French Geographical Society at 184 Boulevard Saint-Germain, Paris from June 18–23 in Paris to discuss more autonomy for the Arab people living under the Ottoman Empire. Furthermore The Arab National Congress, which was established by 25 official Arab Nationalists delegates, was convened to discuss desired reforms and to express their discontent with some Ottoman policies. It took place at a time of uncertainty and change in the Ottoman Empire: in the years leading up to World War I, the Empire had undergone a revolution (1908) and a coup (1913) by the Young Turks, and had been defeated in two wars against Italy and the Balkan states. The Arabs were agitating for more rights under the fading empire and early glimmers of Arab nationalism were emerging. A number of dissenting and reform-oriented groups formed in Greater Syria, Palestine, Constantinople, and Egypt. Under Zionist influence, Jewish immigration to Palestine was increasing, and England and France were expressing interest in the region, competing for spheres of influence.

Nasuhi al-Bukhari or Nasuh al-Boukhari was a Syrian soldier and politician who briefly served as Prime Minister of Syria in 1939.

Muhammad al-Ashmar was a Syrian rebel commander during the Great Syrian Revolt and the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, and a prominent communist figure in post-independence Syria.

Ramaḍān Pāshā al-Shallāsh was a prominent rebel commander of the 1925 Great Syrian Revolt and, prior to that, a military officer in the Ottoman and Sharifian armies.

Shukri al-Asali was a prominent Syrian politician, nationalist leader, and senior inspector in the Ottoman government, in addition to being a ranking member of the Council of Notables. He served in the Ottoman parliament from 1911 until April 1912. He was executed with other Syrian nationalists by the Ottoman governor Jamal Pasha.

Rafīq Bey ibn Mahmūd al-ʿAzm was a Syrian intellectual, author, and politician. 'Azm served as the president of the Ottoman Party for Administrative Decentralization and was a key figure in the intellectual formation of Arabism.

The Syrian Unity party was set up by Syrian emigres in Cairo at the end of 1918. Its founders included signatories to the memorandum that resulted in the Declaration to the Seven and persons previously connected with the Ottoman Party for Administrative Decentralization. In August 1921, the party organized the Syrian–Palestinian Congress in Geneva with a view to influencing the terms of the proposed League of Nations mandate over the region.

Before the outbreak of the First World War, scholars of the Arab Salafiyya movement represented the leading voice of Islamic religious dissent within the Ottoman Empire. Their most influential theologian Muhammad Rashid Rida, an ardent critic of Abdul Hamid II and Turkish nationalism, regarded Ottoman kings as unqualified to rule over the affairs of the Muslim World. While excoriating the Ottomans as an artificial caliphate based on unjust wars and conquests; Salafi scholars nonetheless strongly forbade rebellion against the Ottoman authority due to their insight of dangers posed by the expanding European colonialism. Rashid Rida and his pupils perceived the Ottoman state as an essential entity for allowing Muslims to successfully repel European imperial powers and rebuked the proponents for an alternative Caliphate; suspecting them of serving the aims of imperial powers. All of this changed with the Ottoman entry into World War 1 in October 1914, on the side of the Central Powers. Rashid Rida viewed the war as part of the secular Turkish nationalist programme of the Young Turks, a faction he vehemently denounced as murtadd (apostates).

Abdul Hamid al-Zahrawi was a Syrian Arab nationalist and former member of the General Assembly of the Ottoman Empire. A journalist with the Arab newspaper Al Qabas he supported the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), a Young Turks movement that carried out a successful coup in 1908. Zahrawi sat for the CUP in parliament but turned against them when they started replacing Arab officials with Turks and was replaced in a rigged election in 1912.

References

- ↑ Khoury, Philip S. (2003). Urban Notables and Arab Nationalism: The Politics of Damascus 1860-1920 . Cambridge University Press. pp. 52. ISBN 978-0521533232.

- ↑ Khoury (2003), p.56

- 1 2 Khoury (2003), p.62

- ↑ Memories of A Turkish Statesman 1913-1919 by Djemal Pasha, p. 231

- 1 2 3 Khoury (2003), p.63

- ↑ Rogan, Eugene (2015). The Fall of the Ottomans: The Great War in the Middle East. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0465097425.

- 1 2 Khalidi, Rashid I (Winter 1981). "The Press as a Source for Modern Arab Political History: 'Abd al-Ghani al-'Uraisi and al-Mufid". Arab Studies Quarterly. 3 (1): 26. JSTOR 41857558.

- 1 2 Tauber, Eliezer (Jan 1997). "Secrecy in Early Arab Nationalist Organizations". Middle Eastern Studies. 33 (1): 122. doi:10.1080/00263209708701145. JSTOR 4283850.

- ↑ Tauber (1997), p.123

- ↑ Dawn, C. Ernest (Spring 1962). "The Rise of Arabism in Syria". Middle East Journal. 16 (2): 146. JSTOR 4323468.

- ↑ Bunton, Martin (2016). A History of The Modern Middle East (6th Ed). Westview Press. p. 145. ISBN 978-0-8133-4980-0.