Macroeconomics is a branch of economics dealing with the performance, structure, behavior, and decision-making of an economy as a whole. This includes regional, national, and global economies. Macroeconomists study aggregated indicators such as GDP, unemployment rates, national income, price indices, and the interrelations among the different sectors of the economy to better understand how the whole economy functions. They also develop models that explain the relationship between such factors as national income, output, consumption, unemployment, inflation, saving, investment, international trade, and international finance.

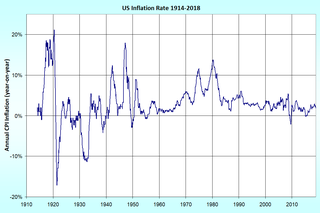

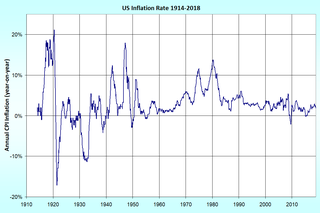

In economics, inflation is a sustained increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy over a period of time. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation reflects a reduction in the purchasing power per unit of money – a loss of real value in the medium of exchange and unit of account within the economy. The measure of inflation is the inflation rate, the annualized percentage change in a general price index, usually the consumer price index, over time. The opposite of inflation is deflation.

Monetarism is a school of thought in monetary economics that emphasizes the role of governments in controlling the amount of money in circulation. Monetarist theory asserts that variations in the money supply have major influences on national output in the short run and on price levels over longer periods. Monetarists assert that the objectives of monetary policy are best met by targeting the growth rate of the money supply rather than by engaging in discretionary monetary policy.

In economics, deflation is a decrease in the general price level of goods and services. Deflation occurs when the inflation rate falls below 0%. Inflation reduces the value of currency over time, but deflation increases it. This allows more goods and services to be bought than before with the same amount of currency. Deflation is distinct from disinflation, a slow-down in the inflation rate, i.e. when inflation declines to a lower rate but is still positive.

New Keynesian economics is a school of contemporary macroeconomics that strives to provide microeconomic foundations for Keynesian economics. It developed partly as a response to criticisms of Keynesian macroeconomics by adherents of new classical macroeconomics.

In economics and political science, fiscal policy is the use of government revenue collection and expenditure (spending) to monitor and influence a nation's economy. It developed out of the Great Depression, when the laissez-faire approach to economic management was ended and government intervention became the means of influencing macroeconomic variables. Fiscal and monetary policy are two sister strategies that are used by the government and the central bank in order to reach a county's economic objectives. The theories of the British economist John Maynard Keynes are the basis for fiscal policy. According to Keynesian economics, when the government changes the levels of taxation and government spending, it influences aggregate demand and the level of economic activity. This influence enables the fiscal authority to target the inflation and to increase employment. Additionally, it is designed to try to keep GDP growth at 2%-3% and the unemployment rate near the natural unemployment rate of 4%-5%. This implies that fiscal policy is used to stabilize the economy over the course of the business cycle.

In economics, the fiscal multiplier is the ratio of a change in national income to the change in government spending that causes it. More generally, the exogenous spending multiplier is the ratio of a change in national income to any autonomous change in spending that causes it. When this multiplier exceeds one, the enhanced effect on national income is called the multiplier effect. The mechanism that can give rise to a multiplier effect is that an initial incremental amount of spending can lead to increased income and hence increased consumption spending, increasing income further and hence further increasing consumption, etc., resulting in an overall increase in national income greater than the initial incremental amount of spending. In other words, an initial change in aggregate demand may cause a change in aggregate output that is a multiple of the initial change.

In economics, crowding out is a phenomenon that occurs when increased government involvement in a sector of the market economy substantially affects the remainder of the market, either on the supply or demand side of the market.

Helicopter money is a proposed unconventional monetary policy, sometimes suggested as an alternative to quantitative easing (QE) when the economy is in a liquidity trap. Although the original idea of helicopter money describes central banks making payments directly to individuals, economists have used the term 'helicopter money' to refer to a wide range of different policy ideas, including the 'permanent' monetization of budget deficits – with the additional element of attempting to shock beliefs about future inflation or nominal GDP growth, in order to change expectations. A second set of policies, closer to the original description of helicopter money, and more innovative in the context of monetary history, involves the central bank making direct transfers to the private sector financed with base money, without the direct involvement of fiscal authorities. This has also been called a citizens' dividend or a distribution of future seigniorage.

In economics, an optimum currency area (OCA), also known as an optimal currency region (OCR), is a geographical region in which it would maximize economic efficiency to have the entire region share a single currency.

In macroeconomics, discretionary policy is an economic policy based on the ad hoc judgment of policymakers as opposed to policy set by predetermined rules. For instance, a central banker could make decisions on interest rates on a case-by-case basis instead of allowing a set rule, such as the Taylor rule, Friedman's k-percent rule, or a nominal income target to determine interest rates or the money supply. In practice most policy actions are discretionary in nature.

Quantitative easing (QE), also known as large-scale asset purchases, is a monetary policy whereby a central bank buys predetermined amounts of government bonds or other financial assets in order to inject money directly into the economy. An unconventional form of monetary policy, it is usually used when inflation is very low or negative, and standard expansionary monetary policy has become ineffective. A central bank implements quantitative easing by buying specified amounts of financial assets from commercial banks and other financial institutions, thus raising the prices of those financial assets and lowering their yield, while simultaneously lowering short term interest rates which increases the money supply. This differs from the more usual policy of buying or selling short-term government bonds to keep interbank interest rates at a specified target value.

In economics, the inside lag is the amount of time it takes for a government or a central bank to respond to a shock in the economy. It is the delay in implementation of a fiscal policy or monetary policy. Its converse is the outside lag. The inside lag comprises the recognition lag and the decision lag.

Optimal tax theory or the theory of optimal taxation is the study of designing and implementing a tax that maximises a social welfare function subject to economic constraints. The social welfare function used is typically a function of individuals' utilities, most commonly a utilitarian function, so the tax system is chosen to maximise the sum of individual utilities. Tax revenue is required to fund the provision of public goods and other government services, as well as for redistribution from rich to poor individuals. However, most taxes distort individual behaviour, because the activity that was being taxed becomes relatively less desirable; for instance, taxes on labour income reduce the incentive to work. The optimization problem involves minimizing these distortions away from the efficient state, caused by taxation, while achieving desired levels of redistribution and provision of public services. Exceptions to this trade-off include non-distortionary taxes, such as lump-sum taxes, where individuals cannot change their behaviour to reduce their tax burden, and Pigouvian taxes, where the market consumption of a good is inefficient and a tax brings consumption closer to the efficient level.

Monetary inflation is a sustained increase in the money supply of a country. Depending on many factors, especially public expectations, the fundamental state and development of the economy, and the transmission mechanism, it is likely to result in price inflation, which is usually just called "inflation", which is a rise in the general level of prices of goods and services.

The Lost Decade or the Lost 10 Years was a period of economic stagnation in Japan following the Japanese asset price bubble's collapse in late 1991 and early 1992. The term originally referred to the years from 1991 to 2000, but recently the decade from 2001 to 2010 is often included so that the whole period is referred to as the Lost Score or the Lost 20 Years. Broadly impacting the entire Japanese economy, over the period of 1995 to 2007, GDP fell from $5.33 trillion to $4.36 trillion in nominal terms, real wages fell around 5%, while the country experienced a stagnant price level. While there is some debate on the extent and measurement of Japan's setbacks, the economic effect of the Lost Decade is well established and Japanese policymakers continue to grapple with its consequences.

In economics, stimulus refers to attempts to use monetary or fiscal policy to stimulate the economy. Stimulus can also refer to monetary policies like lowering interest rates and quantitative easing.

Fiscal union is the integration of the fiscal policy of nations or states. Under fiscal union decisions about the collection and expenditure of taxes are taken by common institutions, shared by the participating governments. Fiscal union also implies that the debt would be financed not by individual countries but by a common bond.

A distributional effect is the effect of the redistribution of the final gains and costs derived from the direct gains and cost allocations of a project. A project has a direct-profit redistribution effect and a direct-cost redistribution effect. But whether it is profit or cost, the redistribution effect can be expressed as a benefit to a group of people or department or region, and the loss to another party. In theory, the indirect profit and indirect costs can also be derived from the redistribution effect, and valued.