Related Research Articles

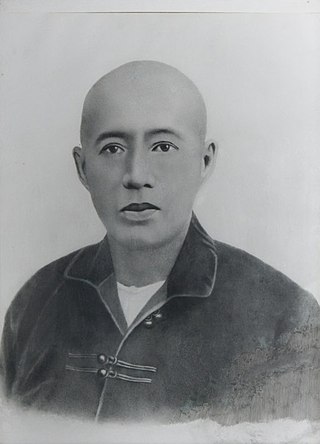

Oei Tiong Ham, Majoor-titulair der Chinezen was a Chinese Indonesian tycoon and the son of Oei Tjie Sien, the founder of the Kian Gwan, a multinational trading company. Born in Semarang, Central Java, Dutch East Indies, he became the wealthiest person in Asia at the start of the twentieth century. Part of his wealth originated in his involvement in the sugar industry. He served as Luitenant der Chinezen in the Dutch colonial administration in Semarang, and was raised to the rank of titular Majoor upon retirement.

Khouw Kim An, 5th Majoor der Chinezen was a high-ranking Chinese Indonesian bureaucrat, public figure and landlord who served as the fifth and last Majoor der Chinezen of Batavia, Dutch East Indies. The Chinese Mayoralty was the highest-ranking, Chinese government position in the East Indies with considerable political and judicial jurisdiction over the colony's Chinese subjects. The Batavian Mayoralty was one of the oldest public institutions in the Dutch colonial empire, perhaps second only in antiquity to the viceregal post of Governor-General of the Dutch East Indies.

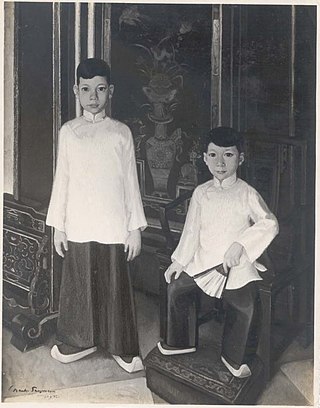

The Khouw family of Tamboen was an aristocratic landowning dynasty of bureaucrats and community leaders, part of the Cabang Atas or the Peranakan Chinese gentry of colonial Indonesia.

Tan Eng Goan, 1st Majoor der Chinezen was a high-ranking bureaucrat who served as the first Majoor der Chinezen of Batavia, capital of colonial Indonesia. This was the highest-ranking Chinese position in the civil administration of the Dutch East Indies.

Khouw Tjeng Tjoan, Luitenant-titulair der Chinezen was a Chinese-Indonesian magnate and landlord.

Sia was a hereditary, noble title of Chinese origin, used mostly in colonial Indonesia. It was borne by the descendants of Chinese officers, who were high-ranking, Chinese civil bureaucrats in the Dutch colonial government, bearing the ranks of Majoor, Kapitein or Luitenant der Chinezen.

Lie Tjoe Hong, 3rd Majoor der Chinezen was a Chinese-Indonesian bureaucrat who served as the third Majoor der Chinezen, or Chinese headman, of Batavia, now Jakarta, capital of Indonesia. This was the most senior Chinese position in the colonial civil bureaucracy of the Dutch East Indies. As Majoor, Lie was also the Chairman of the Chinese Council of Batavia, the city's highest Chinese government body.

The Cabang Atas —literally 'upper branch' in Indonesian—was the traditional Chinese establishment or gentry of colonial Indonesia. They were the families and descendants of the Chinese officers, high-ranking colonial civil bureaucrats with the ranks of Majoor, Kapitein and Luitenant der Chinezen. They were referred to as the baba bangsawan [‘Chinese gentry’] in Indonesian, and the ba-poco in Java Hokkien.

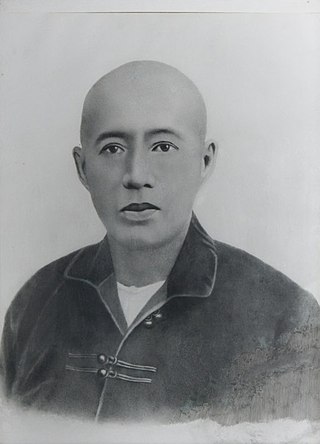

Oei Tjie Sien was a Chinese-born colonial Indonesian tycoon and the founder of Kian Gwan, Southeast Asia's largest conglomerate at the start of the twentieth century. He is better known as the father of Oei Tiong Ham, Majoor-titulair der Chinezen (1866–1924), who modernized and vastly expanded the Oei family's business empire.

Lim Soe Keng Sia, also known as Liem Soe King Sia, Soe King Sia or Lim Soukeng Sia, was a Pachter, or revenue farmer, in Batavia, capital of the Dutch East Indies, best known for his rivalry with the notorious Betawi playboy Oey Tamba Sia. He acted as administrator of the 'Ngo Ho Tjiang' Kongsi, the most influential consortium of opium monopolists in early to mid-19th century Batavia.

The Han family of Lasem, also called the Han family of East Java or Surabaya, was an influential family of the 'Cabang Atas' or the Chinese gentry of the Dutch East Indies. They came to power in the Indies through their alliance with the Dutch East India Company in the 18th century. Originally from Lasem in Central Java, they figured prominently in the consolidation of Dutch rule in East Java and maintained a long tradition of government service as Kapitan Cina and priyayi in the Dutch colonial bureaucracy.

The Kwee family of Ciledug was an influential bureaucratic and business dynasty of the 'Cabang Atas' or the Chinese gentry of the Dutch East Indies. From the mid-nineteenth until the mid-twentieth century, they featured prominently in the colonial bureaucracy of Java as Chinese officers, and played an important role in the sugar industry. Like many in the Cabang Atas, they were pioneering, early adopters of European education and modernity in colonial Indonesia. During the Indonesian Revolution, they also hosted most of the negotiations leading to the Linggadjati Agreement of 1946.

Tan Gin Ho, Luitenant der Chinezen (1880–1941) was a bureaucrat, Malay-language writer and scion of the influential Tan family of Cirebon, part of the ‘Cabang Atas’ gentry of the Dutch East Indies.

Be Biauw Tjoan, Majoor-titulair der Chinezen was one of the most important Chinese-Indonesian magnates in the second half of the nineteenth century. A bureaucrat, revenue farmer (pachter) and businessman, he headed the influential Be family of Bagelen, part of the ‘Cabang Atas’ gentry of the Indies.

Tan Ndjiang Nio (1825–1870), better known as Njonja Majoor Be Biauw Tjoan, was a Peranakan aristocrat of the 'Cabang Atas' elite of the Dutch East Indies. A lynchpin of her class, she was the wife, daughter, granddaughter, sister, daughter-in-law and mother-in-law of Semarang's Majoors der Chinezen. This was the highest rank of the Chinese officership, a branch of the civil bureaucracy through which the Dutch governed their Chinese subjects in the Indies.

Lauw Ho, also spelled Lauw Houw, was a prominent tax farmer (pachter), tycoon and ancestor of the Lauw-Sim-Zecha family, part of the 'Cabang Atas' gentry of the Dutch East Indies.

The Ngo Ho TjiangKongsi, sometimes spelled Ngo Houw Tjiang, was a powerful consortium that dominated the opium pacht or tax farm of the Residency of Batavia, Dutch East Indies in the early to mid-nineteenth century. The pacht was an outsourced tax operation, collecting customs, excise and indirect duties on behalf of the Dutch colonial government.

Tan Tiang Po, Luitenant der Chinezen, also spelled Tan Tjeng Po, was a colonial Chinese-Indonesian bureaucrat, landowner, philanthropist and the penultimate Landheer (landlord) of the domain of Batoe-Tjepper in the Dutch East Indies.

The Lie family of Pasilian was an aristocratic Chinese-Indonesian family of landlords, officials and community leaders, part of the ‘Tjabang Atas’ or the Peranakan Chinese gentry of the Dutch East Indies. For over a century, from 1847 until the 1952, members of the family served as Chinese officers, producing a total of nine office-holders, including Lie Tjoe Hong, the third Majoor der Chinezen of Batavia. The Chinese officership, consisting of the ranks of Majoor, Kapitein and Luitenant der Chinezen, was an arm of the Dutch colonial government with administrative and judicial jurisdiction over the colony's Chinese subjects.

Oey Liauw Kong, Kapitein der Chinezen (1799–1865) was a Chinese-Indonesian high official, Landheer (landlord) and head of the Oey family of Kemiri, part of the 'Tjabang Atas' or Peranakan gentry. He was also the owner of the 18th-century Baroque mansion and Jakarta landmark, Toko Merah.

References

- ↑ F.N. Sickenga, Bijdrage tot de geschiedenis der belastingen in Nederland, Leiden 1864, p. 300-308.

- ↑ Jagtenberg, F.G.A., Willem IV: stadhouder in roerige tijden, 1711-1751 (Nijmegen: Vantilt, 2018).

- ↑ Records of the Cape Colony, from February 1793 to April 1831. Cape of Good Hope: Government of the Cape Colony. 1905. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- 1 2 3 Dick, Howard; Sullivan, Michael; Butcher, John (1993). The Rise and Fall of Revenue Farming: Business Elites and the Emergence of the Modern State in Southeast Asia. New York: Springer. ISBN 978-1-349-22877-5 . Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- 1 2 3 Rush, James R. (2007). Opium to Java: Revenue Farming and Chinese Enterprise in Colonial Indonesia, 1860-1910. London: Equinox Publishing. ISBN 978-979-3780-49-8 . Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kahin, Audrey (2015). Historical Dictionary of Indonesia. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-7456-5 . Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- ↑ Reddy, Thiven (2018). Hegemony and Resistance: Contesting Identities in South Africa. Abingdon-on-Thames: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-351-77868-8 . Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- ↑ Groenewald, Gerald (November 2009). "An early modern entrepreneur: hendrik oostwald eksteen and the creation of wealth in dutch colonial cape town, 1702-1741". Kronos. 35 (1): 7–31. ISSN 0259-0190 . Retrieved 18 May 2020.