Bastet or Bast was a goddess of ancient Egyptian religion, worshipped as early as the Second Dynasty. Her name also is rendered as B'sst, Baast, Ubaste, and Baset. In ancient Greek religion, she was known as Ailuros.

Hathor was a major goddess in ancient Egyptian religion who played a wide variety of roles. As a sky deity, she was the mother or consort of the sky god Horus and the sun god Ra, both of whom were connected with kingship, and thus she was the symbolic mother of their earthly representatives, the pharaohs. She was one of several goddesses who acted as the Eye of Ra, Ra's feminine counterpart, and in this form she had a vengeful aspect that protected him from his enemies. Her beneficent side represented music, dance, joy, love, sexuality, and maternal care, and she acted as the consort of several male deities and the mother of their sons. These two aspects of the goddess exemplified the Egyptian conception of femininity. Hathor crossed boundaries between worlds, helping deceased souls in the transition to the afterlife.

The Second Intermediate Period marks a period when ancient Egypt fell into disarray for a second time, between the end of the Middle Kingdom and the start of the New Kingdom. The concept of a "Second Intermediate Period" was coined in 1942 by German Egyptologist Hanns Stock.

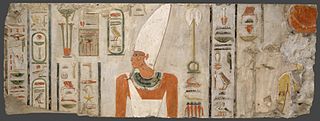

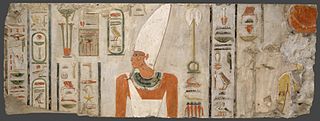

Mentuhotep II, also known under his prenomen Nebhepetre, was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh, the sixth ruler of the Eleventh Dynasty. He is credited with reuniting Egypt, thus ending the turbulent First Intermediate Period and becoming the first pharaoh of the Middle Kingdom. He reigned for 51 years, according to the Turin King List. Mentuhotep II succeeded his father Intef III on the throne and was in turn succeeded by his son Mentuhotep III.

Ancient Egyptian art refers to art produced in ancient Egypt between the 6th millennium BC and the 4th century AD, spanning from Prehistoric Egypt until the Christianization of Roman Egypt. It includes paintings, sculptures, drawings on papyrus, faience, jewelry, ivories, architecture, and other art media. It is also very conservative: the art style changed very little over time. Much of the surviving art comes from tombs and monuments, giving more insight into the ancient Egyptian afterlife beliefs.

The Sixteenth Dynasty of ancient Egypt was a dynasty of pharaohs that ruled the Theban region in Upper Egypt for 70 years.

The Precinct of Mut is an Ancient Egyptian temple compound located in the present city of Luxor, on the east bank of the Nile in South Karnak. The compound is one of the four key ancient temples that creates the Karnak Temple Complex. It is approximately 325 meters south of the precinct of the god Amun. The precinct itself encompasses approximately 90,000 square meters of the entire area. The Mut Precinct contains at least six temples: the Mut Temple, the Contra Temple, and Temples A, B, C, and D. Surrounding the Mut Temple proper, on three sides, is a sacred lake called the Isheru. To the south of the sacred lake is a vast amount of land currently being excavated by Dr. Betsy Bryan and her team from the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, Maryland.

El Lahun. It was known as Ptolemais Hormos in Ptolemaic Egypt.

The Valley of the Kings, also known as the Valley of the Gates of the Kings, is a valley in Egypt where, for a period of nearly 500 years from the 16th to 11th century BC, rock-cut tombs were excavated for the pharaohs and powerful nobles of the New Kingdom.

In ancient Egyptian religion, a menat was a type of artefact closely associated with the goddess Hathor.

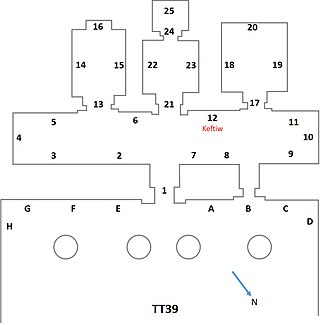

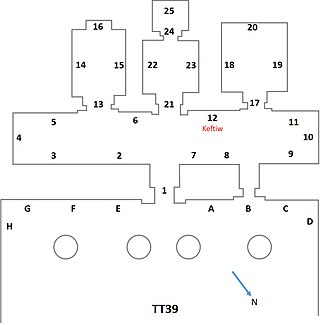

The Theban Tomb TT39 is located in El-Khokha, part of the Theban Necropolis, on the west bank of the Nile, opposite to Luxor. It is the burial place of the ancient Egyptian official, Puimre.

Atlanersa was a Kushite ruler of the Napatan kingdom of Nubia, reigning for about a decade in the mid-7th century BC. He was the successor of Tantamani, the last ruler of the 25th Dynasty of Egypt, and possibly a son of Taharqa or less likely of Tantamani, while his mother was a queen whose name is only partially preserved. Atlanersa's reign immediately followed the collapse of Nubian control over Egypt, which witnessed the Assyrian conquest of Egypt and then the beginning of the Late Period under Psamtik I. The same period also saw the progressive cultural integration of Egyptian beliefs by the Kushite civilization.

Menhet, Menwi and Merti, also spelled Manhata, Manuwai and Maruta, were three minor foreign-born wives of the Eighteenth Dynasty pharaoh Thutmose III who were buried in a lavishly furnished rock-cut tomb in Wady Gabbanat el-Qurud near Luxor, Egypt. They are suggested to be Syrian, as the names all fit into Canaanite name forms, although their ultimate origin is unknown. A West Semitic origin is likely, but both West Semitic and Hurrian derivations have been suggested for Menwi. Each of the wives bear the title of "king's wife", and were likely only minor members of the royal harem. It is not known if the women were related as the faces on the lids of their canopic jars are all different.

Dancing played a vital role in the lives of the ancient Egyptians. However, men and women are never depicted dancing together. The trf was a dance performed by a pair of men during the Old Kingdom. Dance groups were accessible to perform at dinner parties, banquets, lodging houses, and even religious temples. Some women from wealthy harems were trained in music and dance. They danced for royalty accompanied by male musicians playing on guitars, lyres, and harps. Yet, no well-bred Egyptian would dance in public, because that was the privilege of the lower classes. Wealthy Egyptians kept slaves to entertain at their banquets and present pleasant diversion to their owners.

The Theban Tomb TT15 is located in Dra' Abu el-Naga', part of the Theban Necropolis, on the west bank of the Nile, opposite to Luxor. It is the burial place of the ancient Egyptian Tetiky, who was Mayor of Thebes, during the reign of Ahmose I, during the early Eighteenth Dynasty.

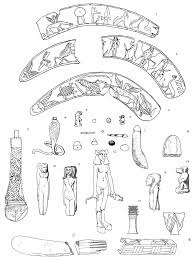

Neferhotep was an ancient Egyptian official with the title scribe of the great enclosure. He lived during the 13th Dynasty, around 1750 BC. His tomb was found in 1860 by Auguste Mariette in Dra Abu el-Naga and contained an important range of objects, most notably of which was the Papyrus Boulaq 18, which is an account of life in the Theban palace. The papyrus had already been published, but the finds in Neferhotep's tomb have only recently been fully published. The tomb contained the rishi coffin of Neferhotep, which was most likely badly decayed when Mariette found it. So it is only known from Mariette's description. Other finds in the tomb are a walking stick, a head rest, a faïence hippopotamus, wooden pieces of the Hounds and Jackals game, a mace, writing implements, a wooden tray for a mirror, two calcite vessels, a magical wand and a double scarab.

The Theban Tomb TT82 is located in Sheikh Abd el-Qurna, part of the Theban Necropolis, on the west bank of the Nile, opposite to Luxor. It is the burial place of the ancient Egyptian official Amenemhat, who was a counter of the grain of Amun and the steward of the vizier Useramen. Amenemhat dates to the Eighteenth Dynasty of Egypt, from the time of Tuthmosis III. As the scribe to the vizier Useramen Amenemhat documents the work in Thebes up to ca year 28. This includes the withdrawal of silver, precious stines and more form the treasury and the manufacture of a number of statues made from silver, bronze and ebony. He also mentions the creation of a large lake near Thebes surrounded by trees and work on the royal tomb.

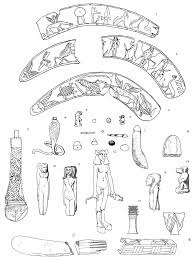

The Malqata Menat was found by the Metropolitan Museum of Art Expedition in 1910, in a private house near the Heb Seds palace of Amenhotep III in Malqata, Thebes. A menat is a type of necklace made up of a series of strings of beads that form a broad collar and a metal counterpoise. The menat could be worn around the neck or held in the hand and rattled during cultic dances and religious processions.

The Ramesseum magician's box is a container discovered in 1885–1886 in a tomb underneath the Ramesseum by Flinders Petrie and James Quibell, containing papyri and items related to magical practices.

Priestess of Hathor or Prophetess of Hathor was the title of the Priestess of the goddess Hathor in the Temple of Dendera in Ancient Egypt.