Weaving is a method of textile production in which two distinct sets of yarns or threads are interlaced at right angles to form a fabric or cloth. Other methods are knitting, crocheting, felting, and braiding or plaiting. The longitudinal threads are called the warp and the lateral threads are the weft, woof, or filling. The method in which these threads are interwoven affects the characteristics of the cloth. Cloth is usually woven on a loom, a device that holds the warp threads in place while filling threads are woven through them. A fabric band that meets this definition of cloth can also be made using other methods, including tablet weaving, back strap loom, or other techniques that can be done without looms.

Tapestry is a form of textile art, traditionally woven by hand on a loom. Normally it is used to create images rather than patterns. Tapestry is relatively fragile, and difficult to make, so most historical pieces are intended to hang vertically on a wall, or sometimes horizontally over a piece of furniture such as a table or bed. Some periods made smaller pieces, often long and narrow and used as borders for other textiles. Most weavers use a natural warp thread, such as wool, linen, or cotton. The weft threads are usually wool or cotton but may include silk, gold, silver, or other alternatives.

Batik is a dyeing technique using wax resist. The term is also used to describe patterned textiles created with that technique. Batik is made by drawing or stamping wax on a cloth to prevent colour absorption during the dyeing process. This creates a patterned negative when the wax is removed from the dyed cloth. Artisans may create intricate coloured patterns with multiple cycles of wax application and dyeing. Patterns and motifs vary widely even within countries. Some pattern hold symbolic significance and are used only in certain occasions, while others were created to satisfy market demand and fashion trends.

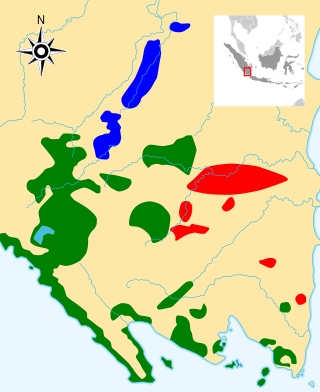

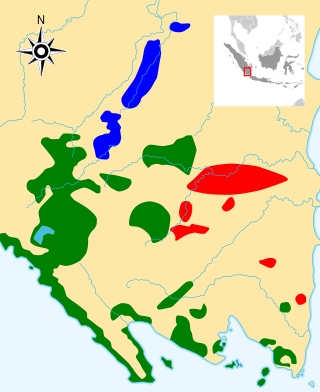

Lampung, officially the Province of Lampung, is a province of Indonesia. It is located on the southern tip of the island of Sumatra. It has a short border with the province of Bengkulu to the northwest, and a longer border with the province of South Sumatra to the north, as well as a maritime border with the provinces of Banten and Jakarta to the east. It is the home of the Lampung people, who speak their own language and possess their own written script. Its capital city is Bandar Lampung.

Ikat is a dyeing technique from Southeast Asia used to pattern textiles that employs resist dyeing on the yarns prior to dyeing and weaving the fabric. In Southeast Asia, where it is the most widespread, ikat weaving traditions can be divided into two general groups of related traditions. The first is found among Daic-speaking peoples. The second, larger group is found among the Austronesian peoples and spread via the Austronesian expansion to as far as Madagascar. It is most prominently associated with the textile traditions of Indonesia in modern times, from where the term ikat originates. Similar unrelated dyeing and weaving techniques that developed independently are also present in other regions of the world, including India, Central Asia, Japan, Africa, and the Americas.

Double cloth or double weave is a kind of woven textile in which two or more sets of warps and one or more sets of weft or filling yarns are interconnected to form a two-layered cloth. The movement of threads between the layers allows complex patterns and surface textures to be created.

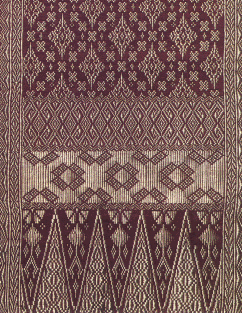

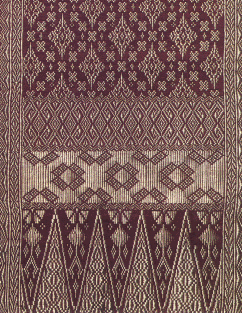

Songket or sungkit is a tenun fabric that belongs to the brocade family of textiles of Brunei, Indonesia, and Malaysia. It is hand-woven in silk or cotton, and intricately patterned with gold or silver threads. The metallic threads stand out against the background cloth to create a shimmering effect. In the weaving process the metallic threads are inserted in between the silk or cotton weft (latitudinal) threads in a technique called supplementary weft weaving technique.

Lampung or Lampungic is an Austronesian language or dialect cluster with around 1.5 million native speakers, who primarily belong to the Lampung ethnic group of southern Sumatra, Indonesia. It is divided into two or three varieties: Lampung Api, Lampung Nyo, and Komering. The latter is sometimes included in Lampung Api, sometimes treated as an entirely separate language. Komering people see themselves as ethnically separate from, but related to, Lampung people.

A sampot, a long, rectangular cloth worn around the lower body, is a traditional dress in Cambodia. It can be draped and folded in several different ways. The traditional dress is similar to the dhoti of Southern Asia. It is also worn in the neighboring countries of Laos and Thailand where it is known as pha nung.

African folk art consists of a variety of items: household objects, metal objects, toys, textiles, masks, and wood sculpture. Most traditional African art meets many definitions of folk art generally, or at least did so until relatively recent dates.

Samite was a luxurious and heavy silk fabric worn in the Middle Ages, of a twill-type weave, often including gold or silver thread. The word was derived from Old French samit, from medieval Latin samitum, examitum deriving from the Byzantine Greek ἑξάμιτον hexamiton "six threads", usually interpreted as indicating the use of six yarns in the warp. Samite is still used in ecclesiastical robes, vestments, ornamental fabrics, and interior decoration.

Tapis is a traditional Tenun style and also refers to resulting cloth that originated from Lampung, Indonesia. It consists of a striped, naturally-coloured cloth embroidered with warped and couched gold thread. Traditionally using floral motifs, it has numerous variations. It is generally worn ceremonially, although it can be used as a decoration. It is considered one of the symbols of Lampung and Lampungese.

Obin, real name Josephine Komara, is a textile designer from Indonesia. She is sometimes called a "national treasure" due to her passion for and promotion of traditional Indonesian batik techniques. Her work has achieved worldwide recognition, with fellow Indonesian designers such as Edward Hutabarat and Ghea Panggabean describing her as the real authority and leader of the mid-2000s movement to update and modernise batik. Despite this, Obin describes herself as simply a tukang kain, or vendor of cloth, stating that the genuine artists and designers are the craftsmen who make the textiles retailed through Bin House, her business.

The national costume of Indonesia is the national attire that represents the Republic of Indonesia. It is derived from Indonesian culture and Indonesian traditional textile traditions. Today the most widely recognized Indonesian national attires include batik and kebaya, although originally those attires mainly belong within the island of Java and Bali, most prominently within Javanese, Sundanese and Balinese culture. Since Java has been the political and population center of Indonesia, folk attire from the island has become elevated into national status.

Balinese textiles are reflective of the historical traditions of Bali, Indonesia. Bali has been historically linked to the major courts of Java before the 10th century; and following the defeat of the Majapahit kingdom, many of the Javanese aristocracy fled to Bali and the traditions were continued. Bali therefore may be seen as a repository not only of its own arts but those of Java in the pre-Islamic 15th century. Any attempt to definitively describe Balinese textiles and their use is doomed to be incomplete. The use of textile is a living tradition and so is in constant change. It will also vary from one district to another. For the most part old cloth are not venerated for their age. New is much better. In the tropics cloth rapidly deteriorates and so virtue is generated by replacing them.

Geringsing is a Tenun textile created by the double ikat method in the Bali Aga village of Tenganan Pegeringsingan in Bali. The demanding technique is only practiced in parts of India, Japan and Indonesia. In Indonesia it is confined to the village of Tenganan.

The textiles of Sumba, an island in eastern Indonesia, represent the means by which the present generation passes on its messages to future generations. Sumbanese textiles are deeply personal; they follow a distinct systematic form but also show the individuality of the weavers and the villages where they are produced. Internationally, Sumbanese textiles are collected as examples of textile designs of the highest quality and are found in major museums around the world, as well as in the homes of collectors.

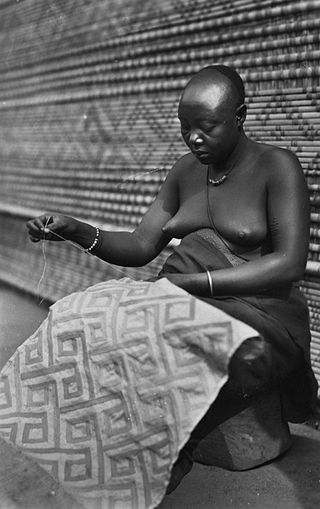

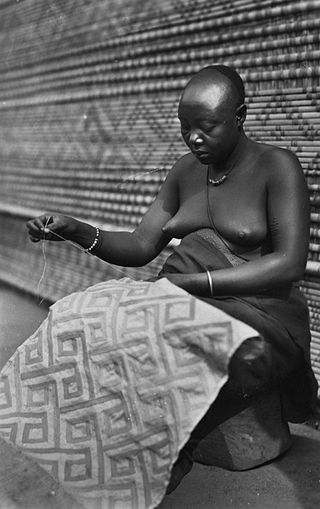

Kuba textiles are a type of raffia cloth unique to the Democratic Republic of the Congo, formerly Zaire, and noted for their elaboration and complexity of design and surface decoration. Most textiles are a variation on rectangular or square pieces of woven palm leaf fiber enhanced by geometric designs executed in linear embroidery and other stitches, which are cut to form pile surfaces resembling velvet. Traditionally, men weave the raffia cloth, and women are responsible for transforming it into various forms of textiles, including ceremonial skirts, ‘velvet’ tribute cloths, headdresses and basketry.

The Khalili Collection of Swedish Textiles is a private collection of textile art assembled by the British scholar, collector and philanthropist Nasser D. Khalili. The collection was built up over a period of 25 years and contains 100 works. It is one of eight collections assembled, conserved, published and exhibited by Khalili, each of which is considered among the most important in its field. In 2008 it was described as "the only extensive collection of Swedish flatweaves outside the country". The collection consists mostly of textile panels, cushion and bed covers from the Scania region of southern Sweden, dating in the main from a hundred-year period between the mid-18th and mid-19th centuries. The majority of the pieces in the collection were made for wedding ceremonies in the region. While they played a part in the ceremonies, they were also a reflection of the artistry and skill of the weaver. Their designs often consist of symbolic illustrations of fertility and long life. Khalili writes that he created the collection because of the tendency of art historians and the public to undervalue art whose creators are anonymous.

Batik plays multiple roles in the culture of Indonesia. The wax resist-dyeing technique has been used for centuries in Java, and has been adopted in varying forms in other parts of the country. Java is home to several batik museums.